The End

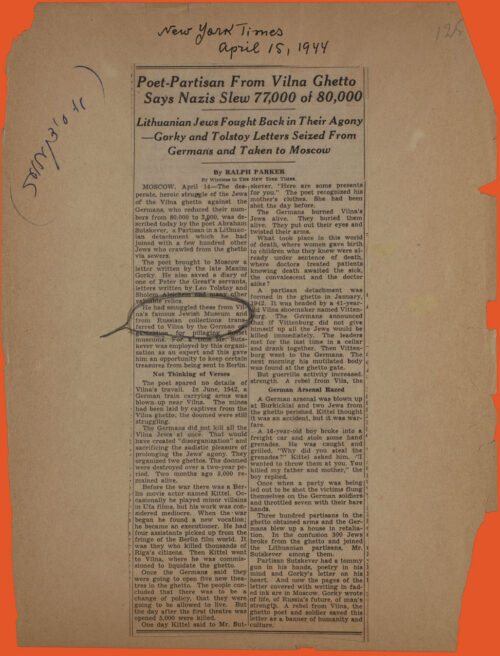

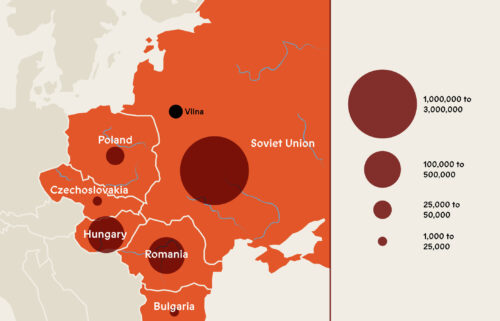

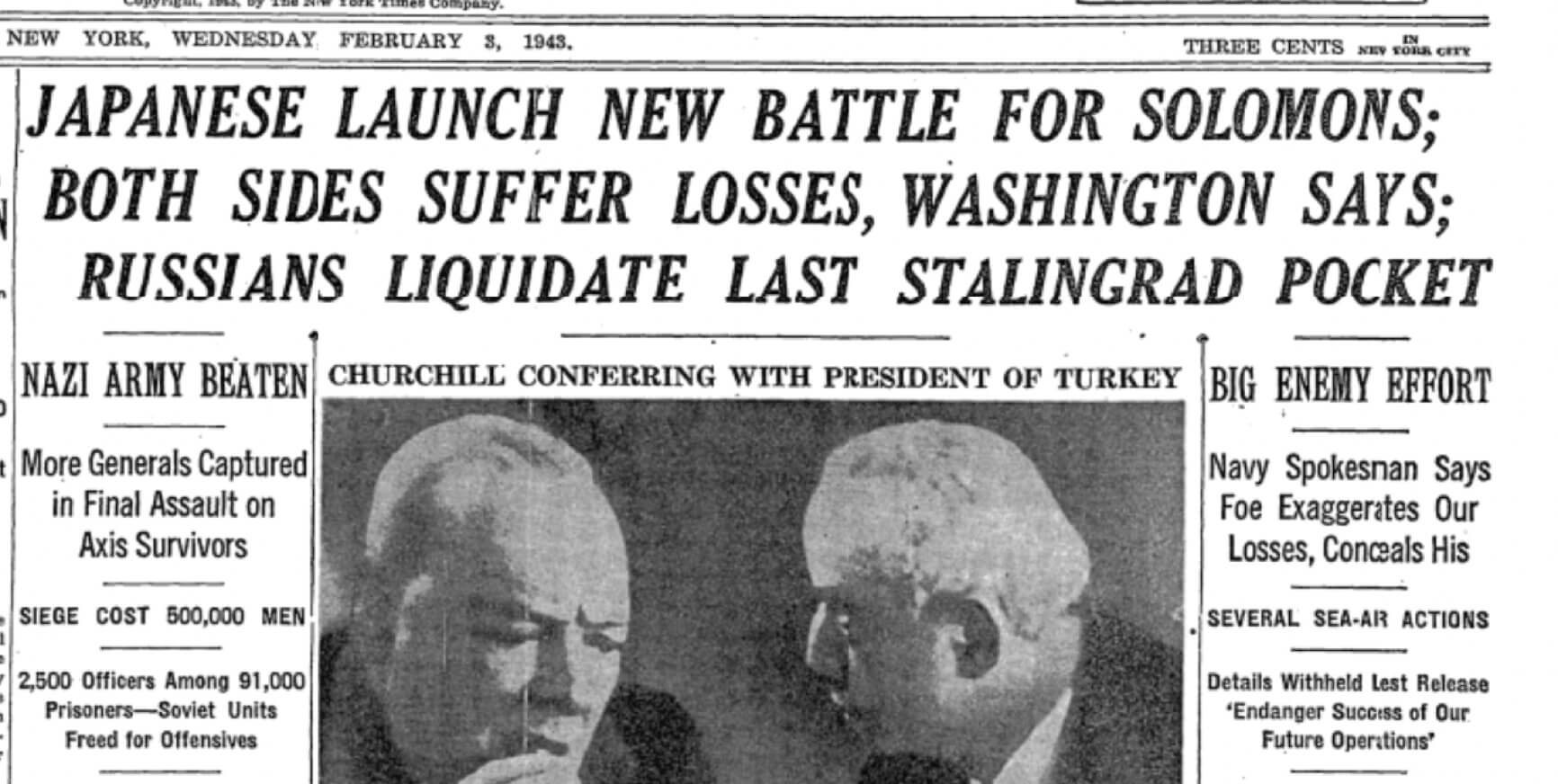

Residents of the Vilna Ghetto lived in constant fear that the Germans would empty it and send all of its inhabitants to their deaths before liberation could arrive. Although they had no concrete information about the Nazis’ plan to murder all of Europe’s Jews, they heard rumors and scraps of news about neighboring ghettos being emptied. This made them fear the worst – especially when the “quiet period” ended and aktions in the ghetto became common again.

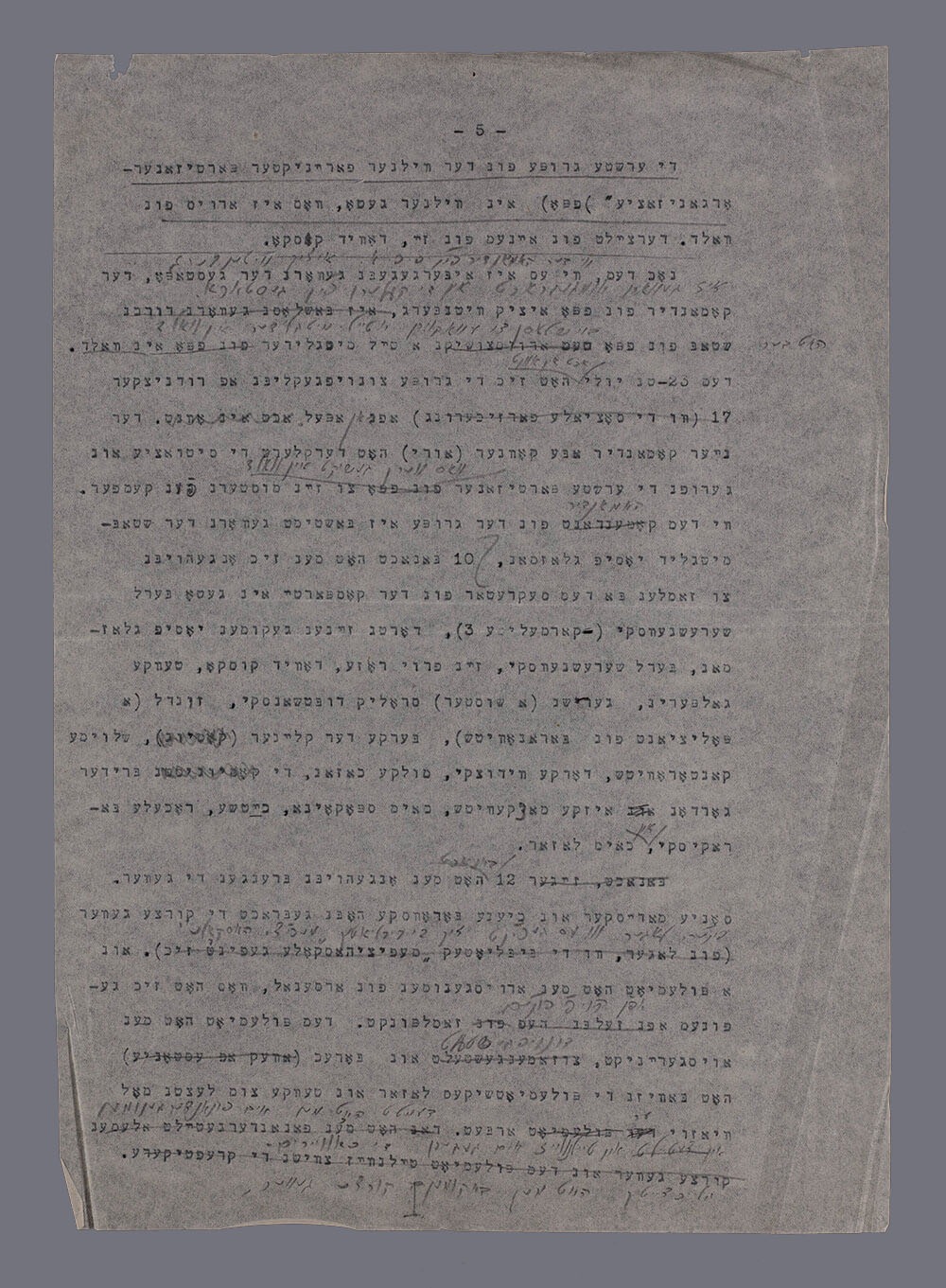

“An order was issued by the German authorities concerning the liquidation of 5 small ghettos in the Vilna region. The Jews are being transferred to the Vilna and Kovno ghettos. Today the Jews from the neighboring small towns are already beginning to arrive. In the street it is rainy and gray. The peasant carts sadly enter the ghetto like Gypsy covered wagons. On the carts sit Jews with children and their bag and baggage. The newly arrived Jews have to be provided with places to live. The school at 1 Shavler Street has been taken over for the newly arrived Jews. The school at 1 Shavler Street has moved into the building of our school. Classes are held in two shifts. Today we already went to class in the evening. School doesn’t make any sense. All of us are depressed. The mood is gloomy.”

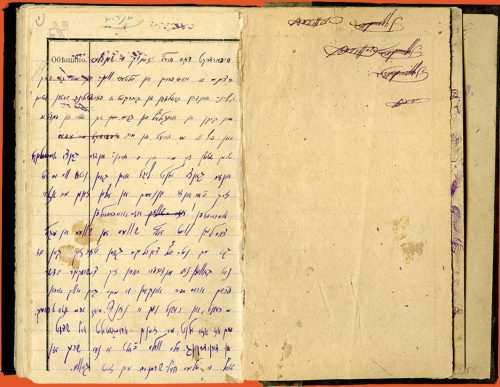

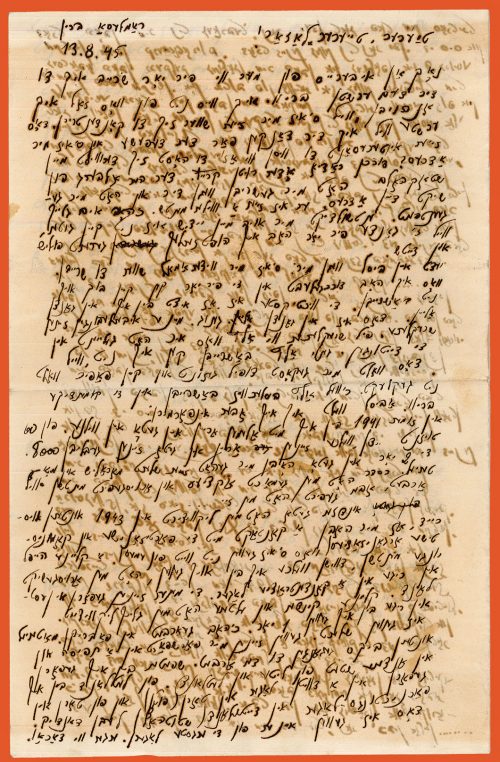

![Letter written Sunday the 28th [of March 1943].](https://museum.yivo.org/wp-content/themes/yivo/images/the-war-ends/Letter_March_28_1943.jpg)

“The mood in the ghetto is very oppressive. Squeezing so many Jews into one place is a signal of something. Bringing food through the gate has become very difficult. Several people have already been arrested and sent to Lukishki Prison. People go around gray and preoccupied. Danger lurks in the air. No! This time we will not let ourselves be led like dogs to slaughter! We have been talking about this lately at our [Pioneer meetings]. We are ready for every moment. We have to work on ourselves. This thought strengthens our nerves, restores our courage and endurance.”

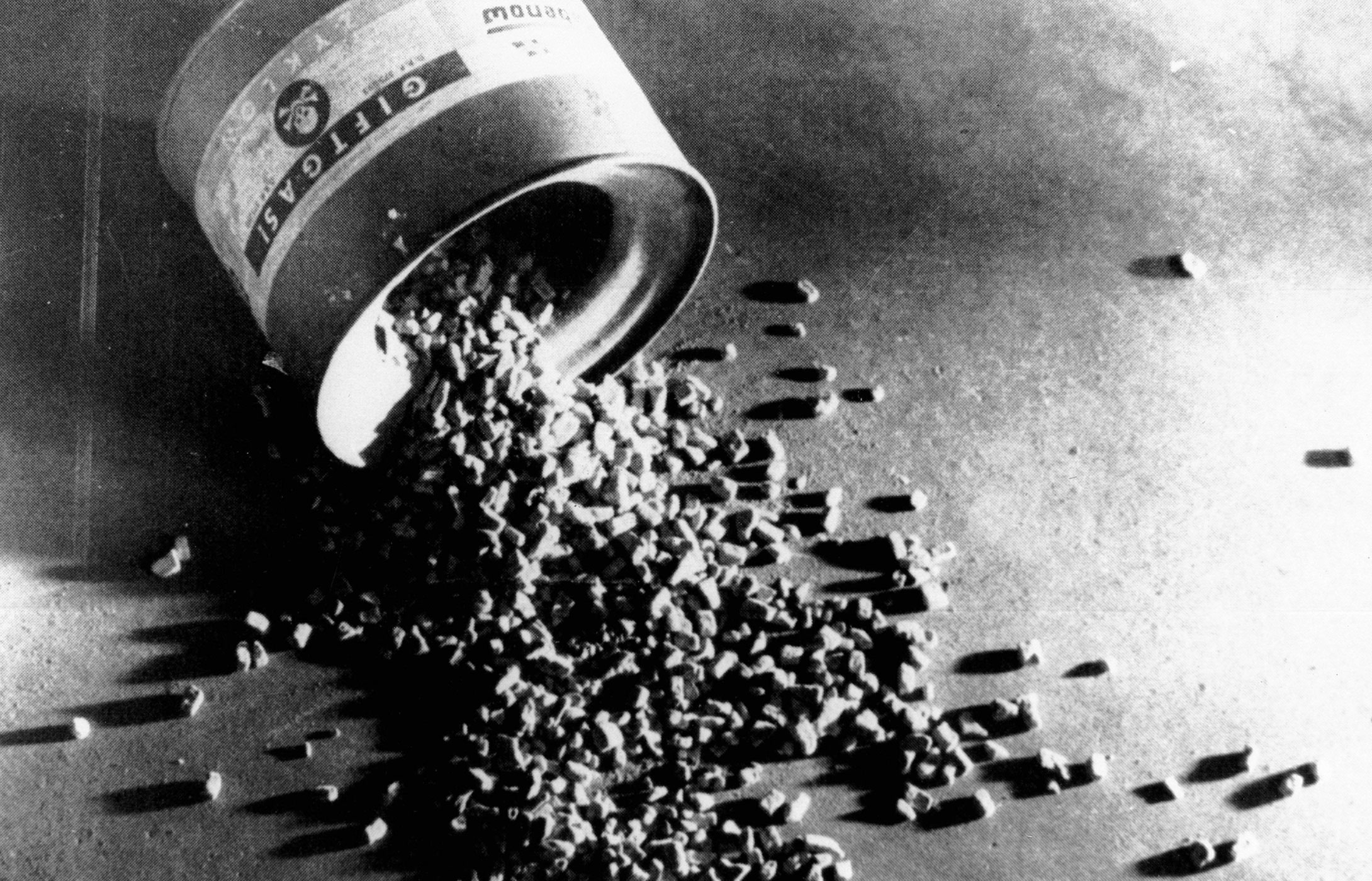

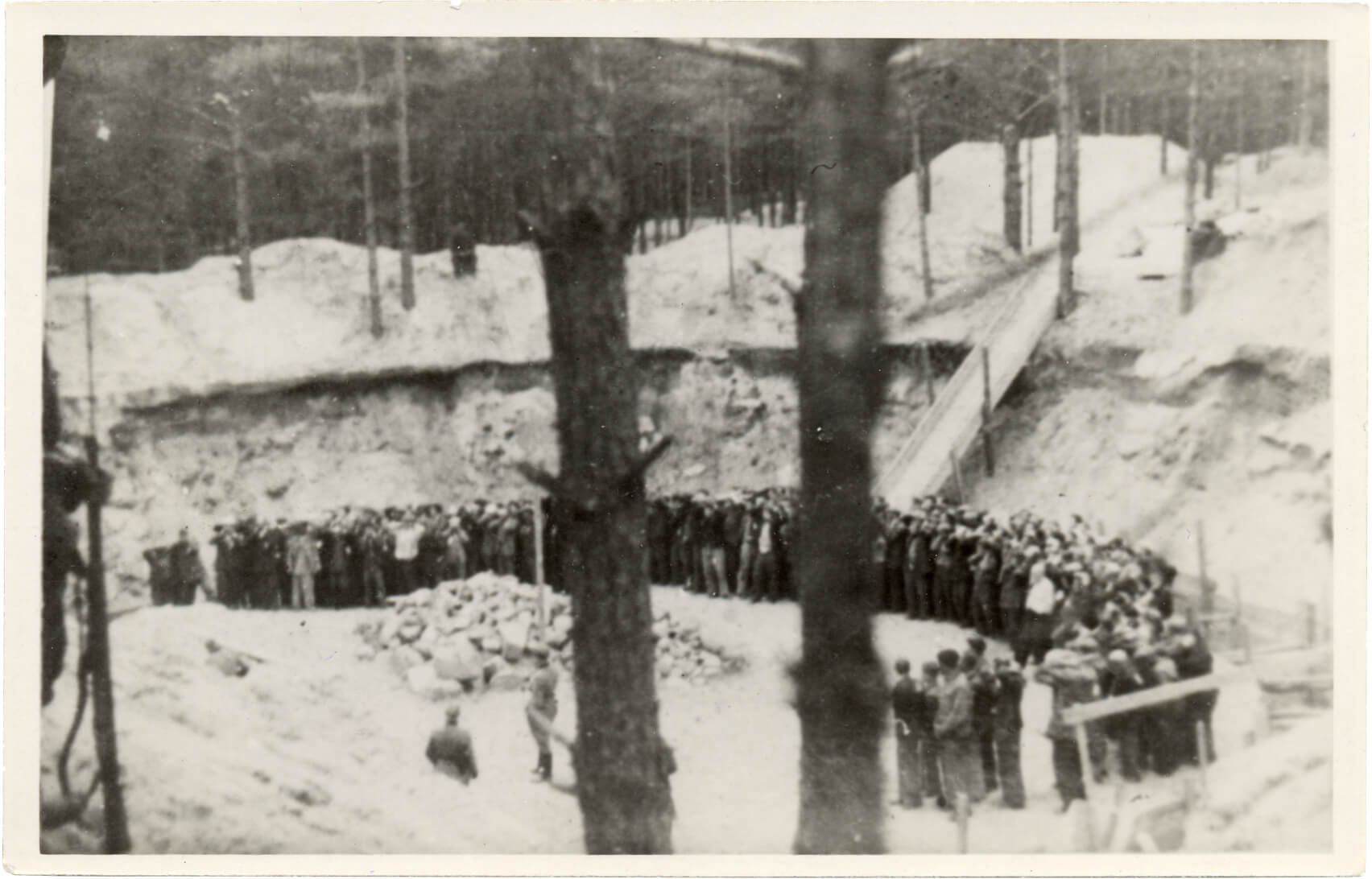

“Sunday at 3 o’clock the streets were closed off in the ghetto. A group of 300 people, from the Jews of Sol and Smorgon, went away to Kovno on a large transport. A transport of Jews from the region had arrived at the railway station. Standing at the gate, I could see them packing. Happily and in a good mood they went to the train. Today we received the terrifying news: 85 railway cars of Jews, about 5000 people, were not taken to Kovno as they had been promised, but were taken by train to Ponar, where they were shot to death. 5000 new bloody victims. The ghetto was profoundly shaken, as if struck by a thunderclap. The mood of massacre has taken hold of the population. It has begun again. The claws of the hawk have appeared before us again. People sit confined in a crate and on the other side lurks the enemy, who is preparing to annihilate us in a refined way according to a plan, as today’s massacre has shown. The ghetto is dejected and saddened. We are defenseless and faced with death. Once again the nightmare of Ponar hovers over the little ghetto streets. It is terrible, terrible. People are walking around like the living dead. They wring their hands. In the evening an urgent meeting: the situation is clear-cut. We have no one to rely on. The danger is very great. We have confidence in our own strength. We are ready at any minute.”

“The situation is oppressive. All the terrifying details are now already known. Instead of to Kovno, 5000 Jews were taken to Ponar where they were shot to death. Like wild animals faced with death they began as a matter of life and death to break out of the railway cars. The broke the little windows that were fortified with strong wires. Hundreds of Jews were shot while running away. The railway lines are covered with the dead for a long stretch. There were no classes in school today. Children are running away from their homes where it is terrible to remain because of the mood there, because of the women. At school the teachers are devastated as well. So we sit in a circle. We pull ourselves together. We sing a song. In the evening I went out into the street. It is 5 o’clock in the afternoon. The ghetto looks dreadful. Heavy leaden clouds move over the ghetto and envelop it. It is dark like before a storm. Our mood, like the sky, is overcast. The streets are filled with people, lost and frightened. 25 policemen were taken to clear away the dead from the pits. Many survivors have escaped from Ponar. Here comes a Jew and after him a crowd of people. He is pale, with wild eyes. His coat is entirely covered with lime. Here they are leading in three children brought by peasants. Wounded are being brought in. It keeps getting darker. Suddenly, thunder and lightning and it starts to rain. The anxious, unhappy people are driven off the couple of little streets with whips. The rain pours angrily, as if it wished to wash everything away from the world. At night I am at the Club. It is dark. The lights won’t come on until 9 o’clock. So we sit in the dark. The group sings a song. It feels oppressive and painful. The situation is still very tense. We are on guard. Yes, that very thought relieves the difficult hours.”

“The mood has improved a little. In the Club you can already hear a happy little song. But we are prepared for everything, because Monday has revealed that we must trust nobody, believe nobody.”

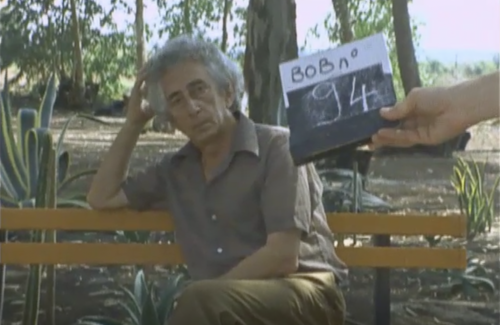

This was the last time Rudashevski wrote in his diary. Everything we know beyond April 7th, we know through the brave efforts of his cousin Sore, who was the family’s sole survivor.

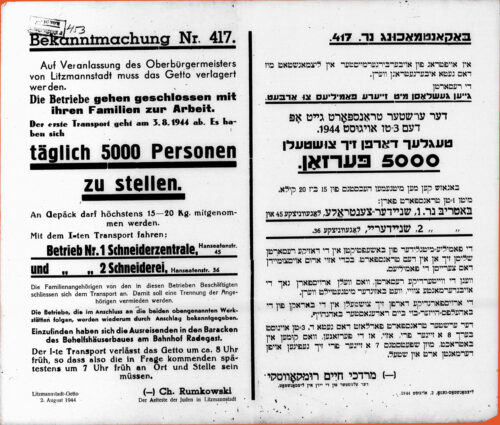

As the horrifying news of ghettoes being emptied of their inhabitants made its way to Vilnius, Yitskhok Rudashevski and his family prepared for the worst. They knew that, sooner or later, the Germans would come for them, as well. Some ghetto dwellers were sent to labor camps in Estonia, but most remained trapped, with no choice but to prepare malines (hiding places) and hope that they could somehow survive.

On September 23rd, 1943, the Germans ordered everyone in the ghetto to report to the gate. After months of aktions, everyone in the ghetto knew what this meant. Sore bundled up photos of her family as quickly as she could. Rudashevski stuffed his diary in his coat pocket and ran to his cousin’s house with his parents. He, his parents, Sore, her sister, her mother, and five neighbors met at the bottom of a flight of stairs and breathed fresh air one more time before hurrying, one by one, into the attic.

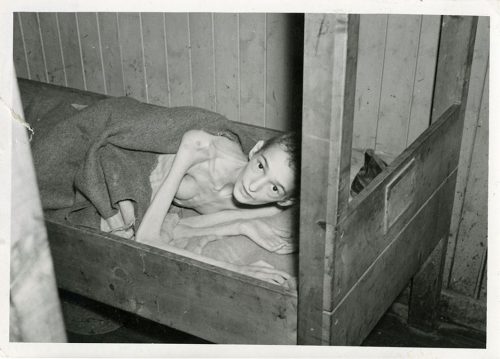

Life in the maline was a terrifying existence in limbo: Everyone was in constant fear of being discovered. The space was small, overcrowded, and stuffy. Sore later remembered that Yitskhok was quiet and depressed, not writing and barely speaking. The Germans shut off the water in the building to flush out any ghetto inhabitants left hiding, leaving them only the water and supplies that were stashed prior to the liquidation. Everyone in the maline knew that their supplies would not last forever. They had one glimmer of hope: News had spread that the Soviet Army was advancing throughout Eastern Europe, liberating ghettos one by one. Their sole focus was to somehow survive in the maline until the Soviet Army could arrive to liberate the ghetto.

The family held out for 11 days. Finally, with no water left, someone had to venture out in hopes of somehow, miraculously, finding water to bring back without getting caught.

But the worst happened. The person sent out for water for the inhabitants of the maline was followed and caught. Forced to give up the location of the maline, all of those in hiding, including Rudashevski, were captured and taken to prison. Rudashevski left his diary on the floor when he was led away. Within days, all of the inhabitants of the maline, except for Sore, were shot and killed at Ponar.