World War II Arrives in Vilna

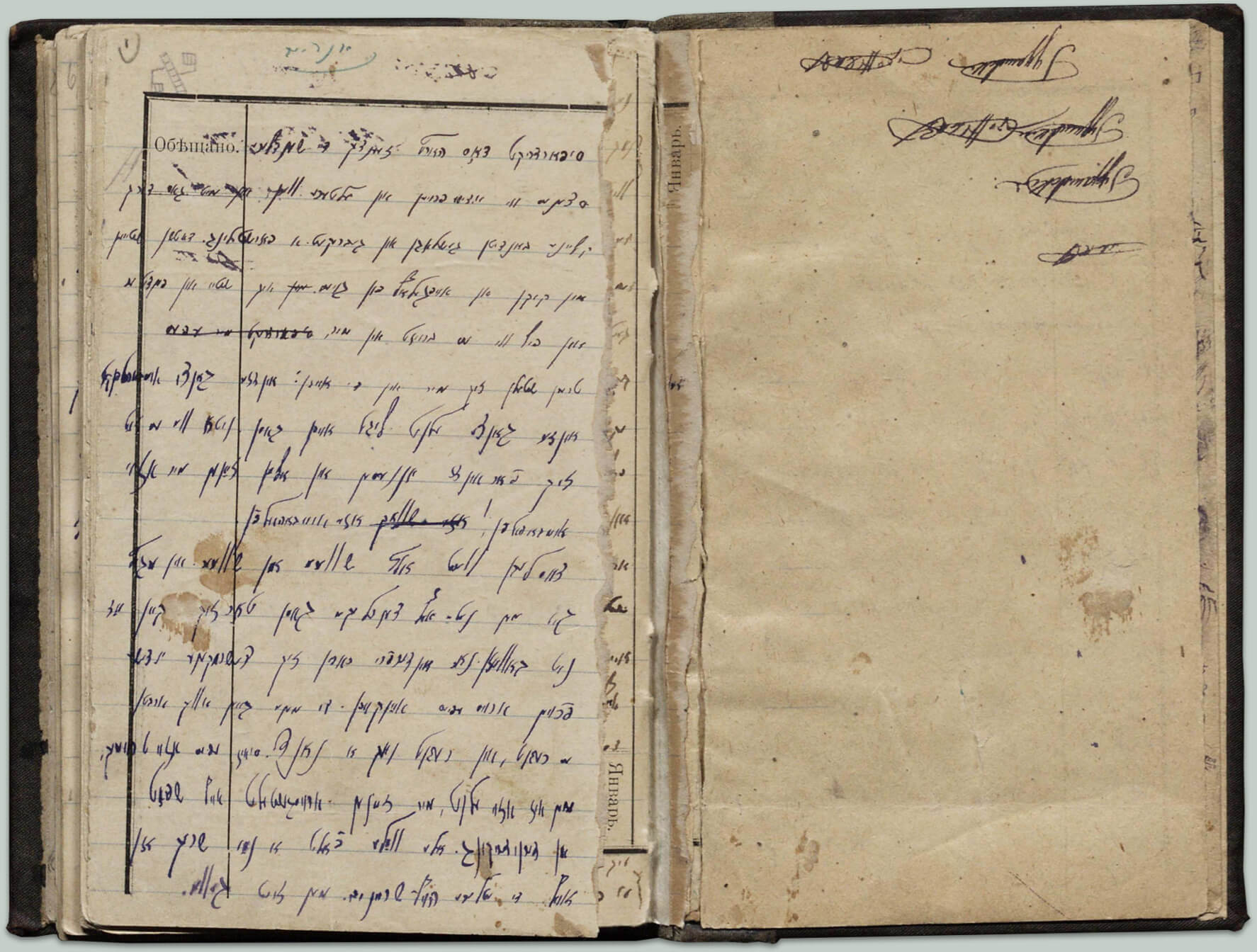

Though Rudashevski would likely have heard rumors of war sweeping across Europe through news and letters, nobody could have known how drastically daily life in Vilna would change. Let’s find out how Rudashevski experienced the first two years of the war. This chapter contains three parts.

The Outbreak of the Second World War and Soviet occupation (Sep 1939 –Jun 1941)

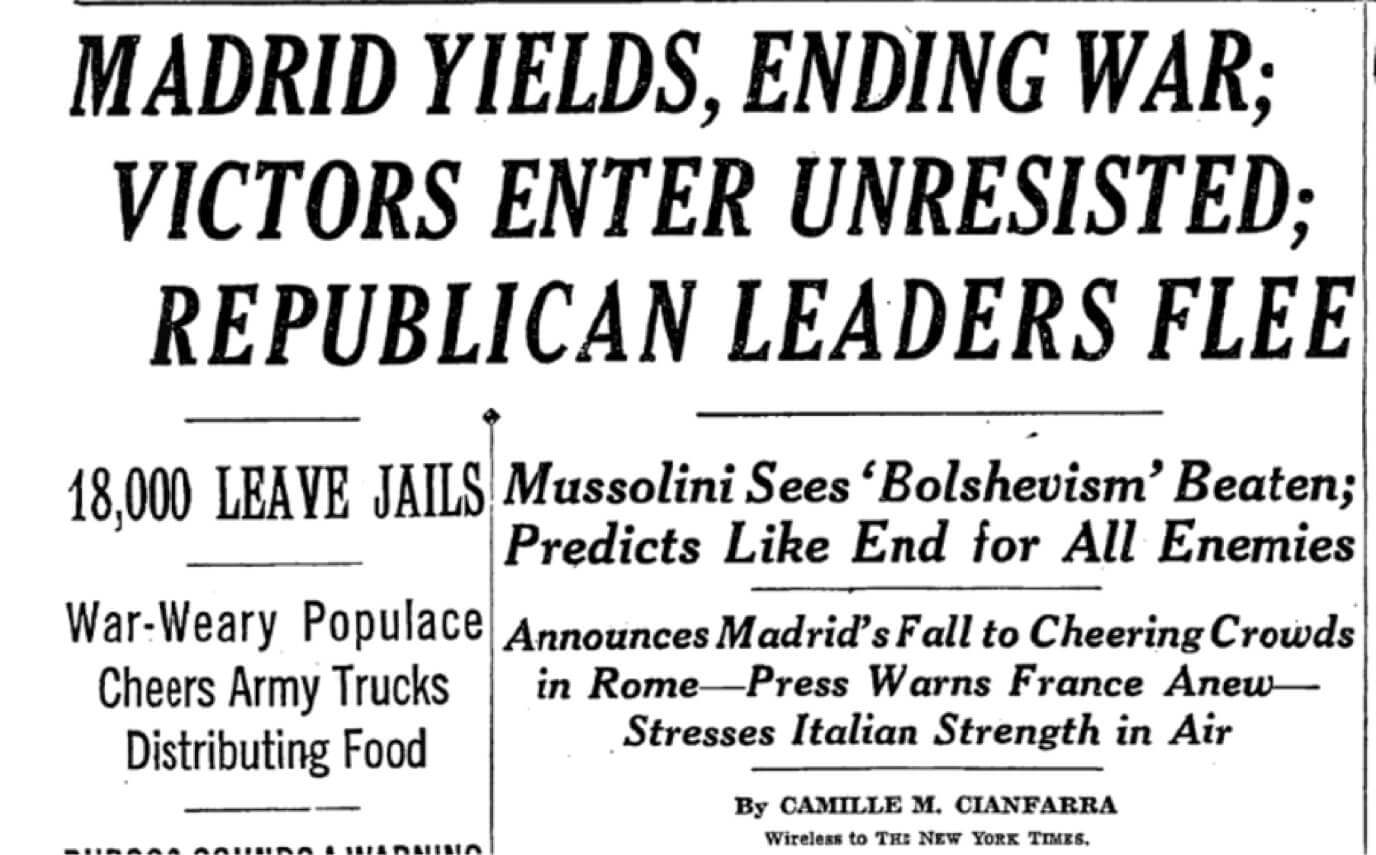

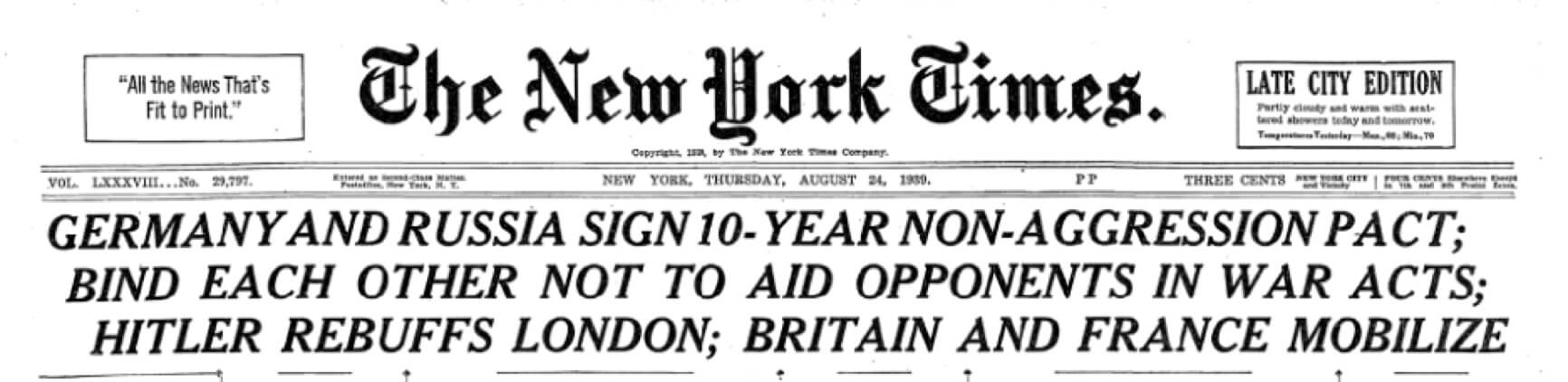

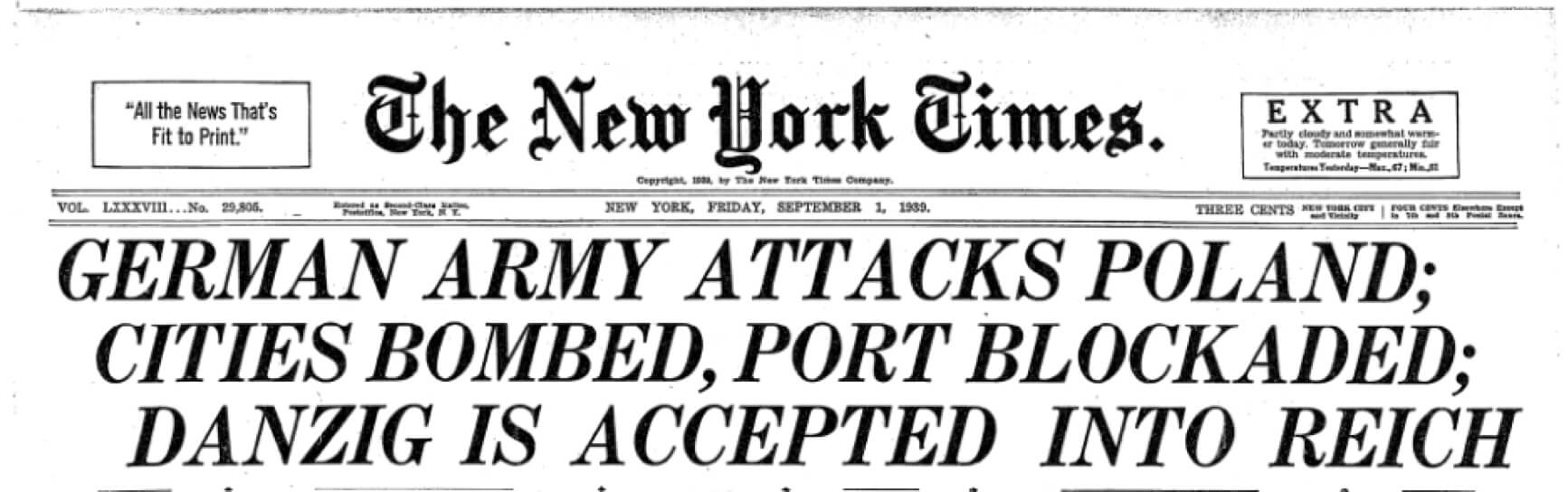

On September 1st, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, marking the beginning of the Second World War in Europe. The huge, powerful German army wiped out the Polish military resistance in a little over a month – in a Blitzkrieg, or “lightning war,” involving an overwhelming combination of tanks, motorized infantry, artillery, and aircraft attacks.

Poland was also destroyed by a surprise attack from the Soviet Army, which invaded from the East 16 days after the Germans invaded from the West. The Soviets had made a secret bargain with Germany called the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, in which the two giant states planned to divide Eastern Europe between them.

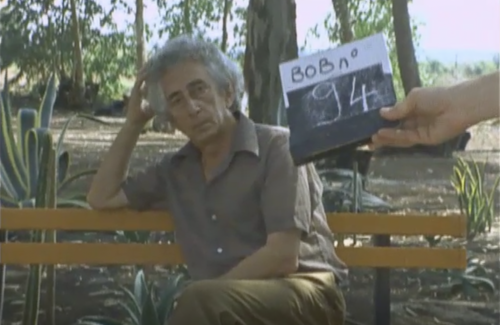

On September 19, 1939, Vilna was captured by the Red Army. At first, Yitskhok Rudashevski welcomed the Red Army tanks and soldiers with excitement, but his enthusiasm was short-lived: a Soviet administration was in power for only 40 days. Then, Vilna was turned over to Lithuania.

In the end, Lithuanian rule in the city, now called Vilnius, lasted fewer than eight months. While tense, this period felt stable to the Jewish community. The Lithuanian government allowed Jewish life, education, and institutions to function, and the city felt like a refuge between the Nazi and Soviet regimes. Around 50,000 war refugees fled to Lithuania. Refugees from Poland flooded into the city. More than half of them stayed in Vilnius and nearby towns. Many of the new arrivals were Polish Jews fleeing Nazi persecution and bringing terrible news. They told local citizens about the danger sweeping across Europe, and Rudashevski and those around him began to clearly feel the threats of war.

There were enormous national tensions simmering in Vilnius. Two-thirds of the city's population were Polish, most of whom viewed the Lithuanians as foreign invaders. More than a quarter of the city's population were Jews like Rudashevski, who had previously been citizens of the Polish state. Lithuanians themselves were a small minority in Vilnius. Lithuanian authorities were introducing the compulsory use of the Lithuanian language, which most Vilnius residents did not speak.

The street where Rudashevski lived before the war had been called Zawalna (Rampart Street) in Polish. It now became Pylimo (Castle Street) in Lithuanian. At his school, the Real Gymnasium, Polish language and history were replaced by Lithuanian subjects. The new Lithuanian government attempted to reshape Polish (or Yiddish) Vilna into Lithuanian Vilnius by changing its culture, but this only increased hostility from the Polish-speaking community. Under the stable surface of the city's life, major national conflicts were about to boil over.

Later, in mid-June 1940, Lithuania became part of the Soviet Union. Vilnius became the capital of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. Education in Yitskhok Rudashevski‘s school had changed again. Now Russian language, Soviet history, and Communism were being taught alongside Yiddish and the other subjects.

As a member of a youth Communist group called the Pioneers, Rudashevski was enthusiastic about prospects for the future.

“I recall how almost exactly a year ago I welcomed the Red Army in a little Lithuanian town. We ran for several kilometers to greet the first Soviet tank that had stopped there.”

"Schoolwork is over. The days are sunny, warm. I feel like getting out of the city. We, the Pioneers, are going to a Pioneer meeting in our school yard. We walk along the Vilna streets that are bathed in sunlight. All we talk about is going to the camps. The group dreams of green fields and of cheerful camp life. The group yearns to get out of town. We travel by steamer to Verek. We are greeted by sunny greenery. In the evening we return to the noisy city that teems with life, with people, with the Red Army men’s singing and laughter.”