The Quiet Period

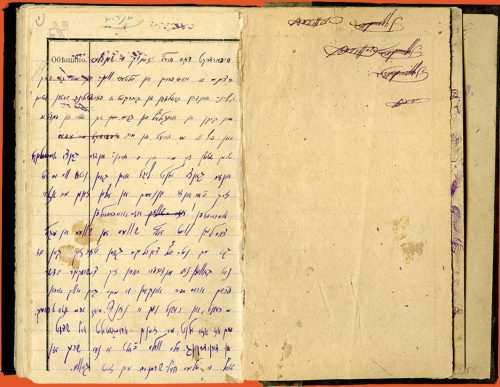

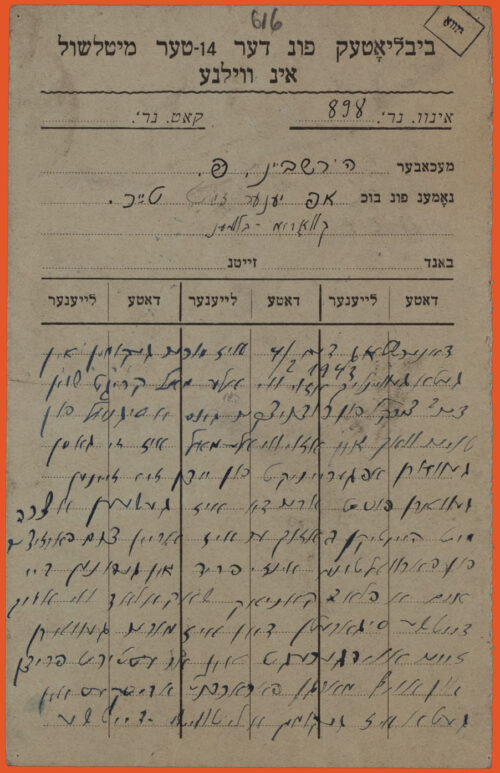

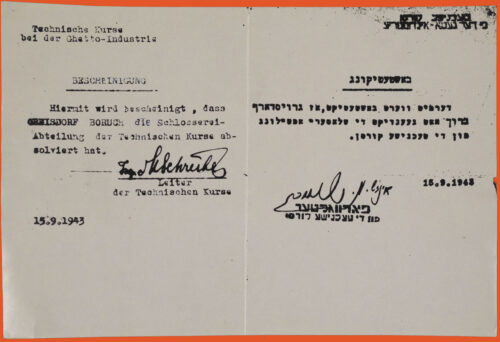

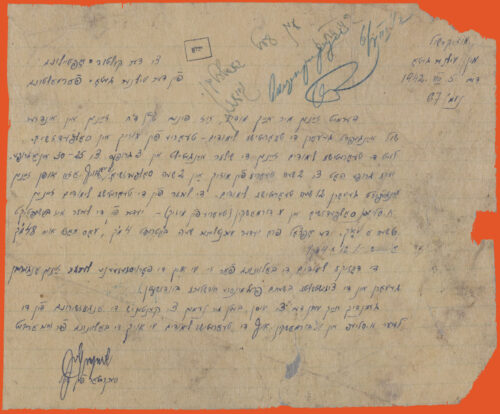

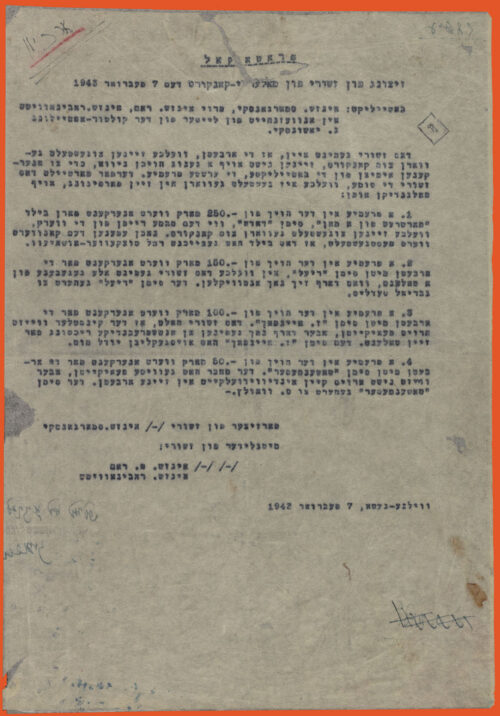

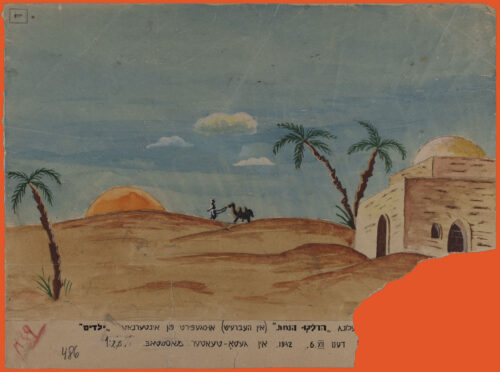

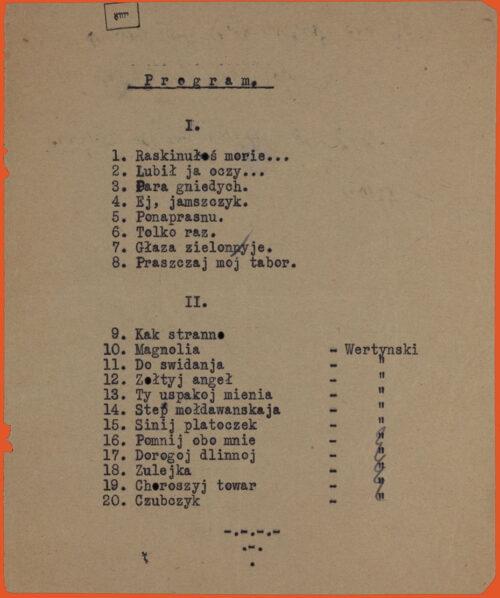

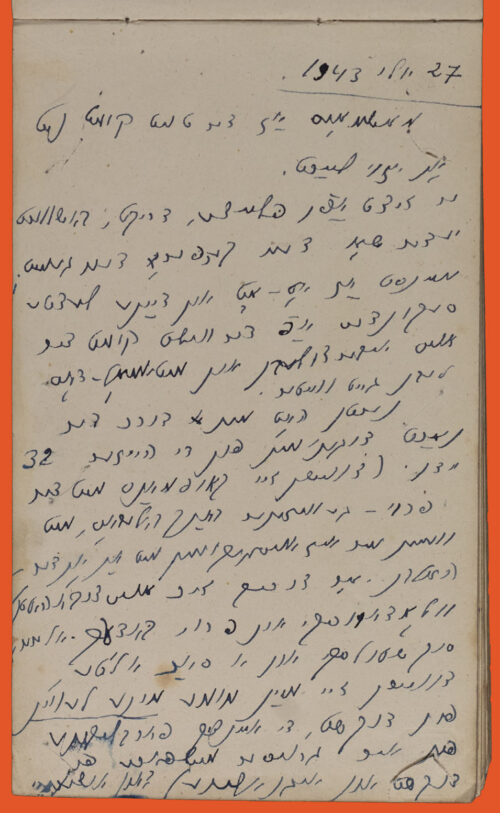

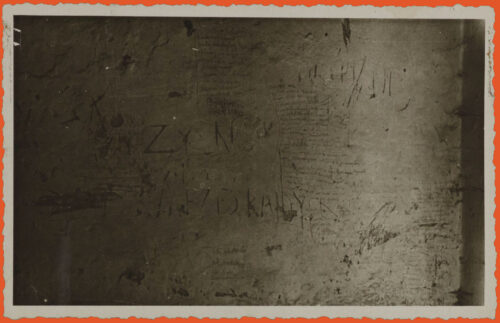

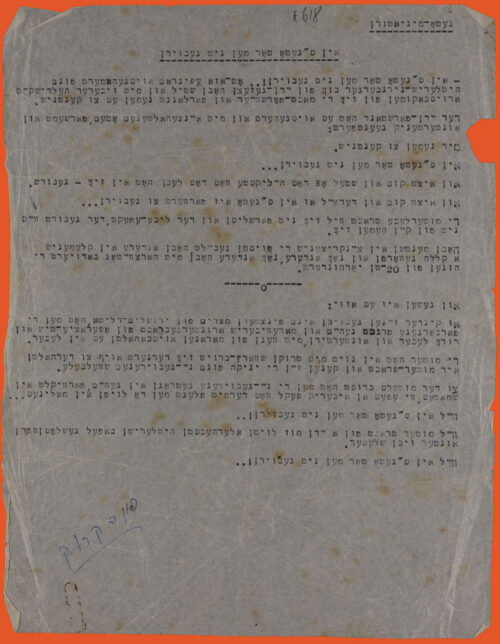

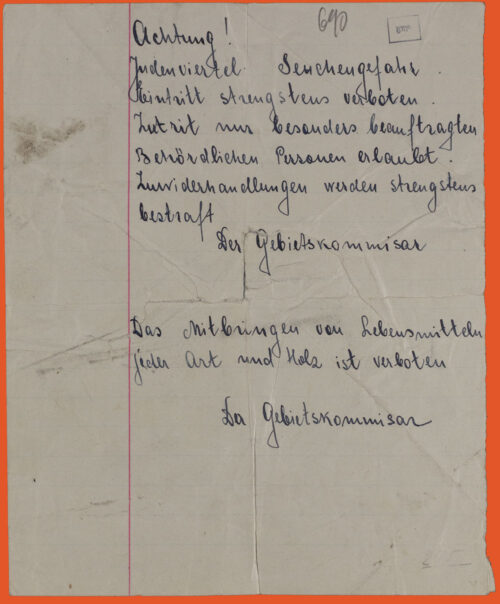

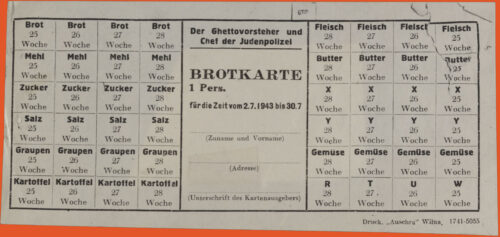

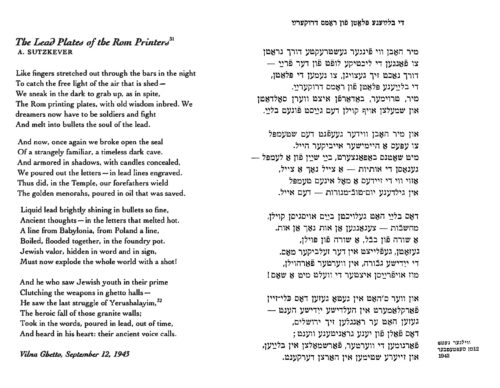

After the many aktions in the Vilna Ghetto in 1941, only half of the ghetto’s initial population remained. Life then gradually became “normalized.” Little by little, Jews began to build a life within the ghetto. There were gatherings, schools, a library—all happening under the shadow of repression and terror from the Nazi regime. The German goal was not only to exterminate the Jewish people, but to kill Jewish culture altogether. Resistance through maintaining Jewish culture was another way to fight Nazi tyranny. Rudashevski chronicles many such acts of resistance in his diary, which we can see below by way of different experiences.

Moral and Ethical Dilemmas

Here are entries from Rudashevski’s diary where he reflects on moral and ethical dilemmas in the Vilna Ghetto. He describes scenes of corruption from those who should be allies and what he observes about moments of weakness that exemplify the human condition.

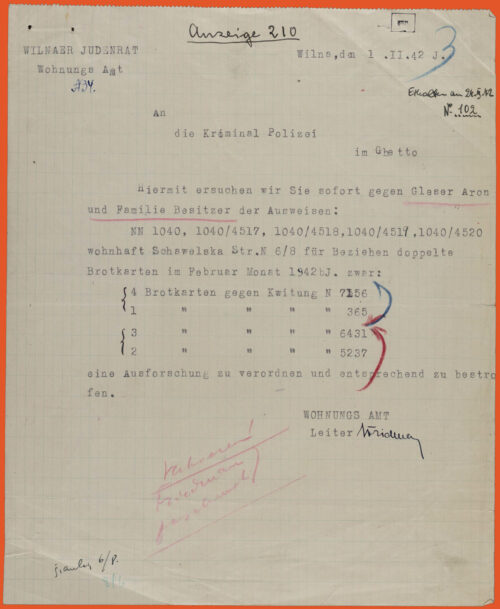

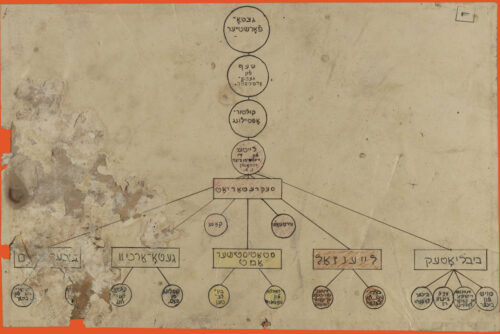

The Jewish Police

The Butcher

During the Holocaust, people found themselves facing unprecedented moral and ethical dilemmas. The individual instinct for survival could, in many cases, conflict with moral imperatives such as justice and shared human responsibility. These dilemmas played out in every context, from the family home to the wider ghetto community. For example, throughout the diaries and memoirs of the period, Jews documented the way that scarcity – of food, fuel, and other necessities – sometimes caused people to hoard or steal from strangers or their own loved ones. This brought added shame and guilt to an already excruciating existence.

On a broader scale, individuals sometimes made choices that they thought would increase their personal or family’s chances of survival, even if it meant acting against the interests of the community as a whole. For example, some who joined the Jewish police or served on the Jewish Councils could gain material advantages for themselves or their families – deferred deportation, extra food, or other privileges – even as they had to collude with or carry out German directives. In some cases, people who made decisions to benefit themselves justified them by saying that if they did not do it, someone else would. In other words, in an entirely corrupt system, the abstract idea of morality crumbled under the imperative of survival.

Tragically, these kinds of moral compromises rarely truly had the power to change the ultimate outcomes of a person’s life. Determined as they were to kill each and every Jew in Europe, the Germans exploited people’s desperation with no intention of rewarding their behavior. Those who compromised their values in the interest of survival may have bought themselves more time, but they rarely changed their fate.