The Quiet Period

After the many aktions in the Vilna Ghetto in 1941, only half of the ghetto’s initial population remained. Life then gradually became “normalized.” Little by little, Jews began to build a life within the ghetto. There were gatherings, schools, a library—all happening under the shadow of repression and terror from the Nazi regime. The German goal was not only to exterminate the Jewish people, but to kill Jewish culture altogether. Resistance through maintaining Jewish culture was another way to fight Nazi tyranny. Rudashevski chronicles many such acts of resistance in his diary, which we can see below by way of different experiences.

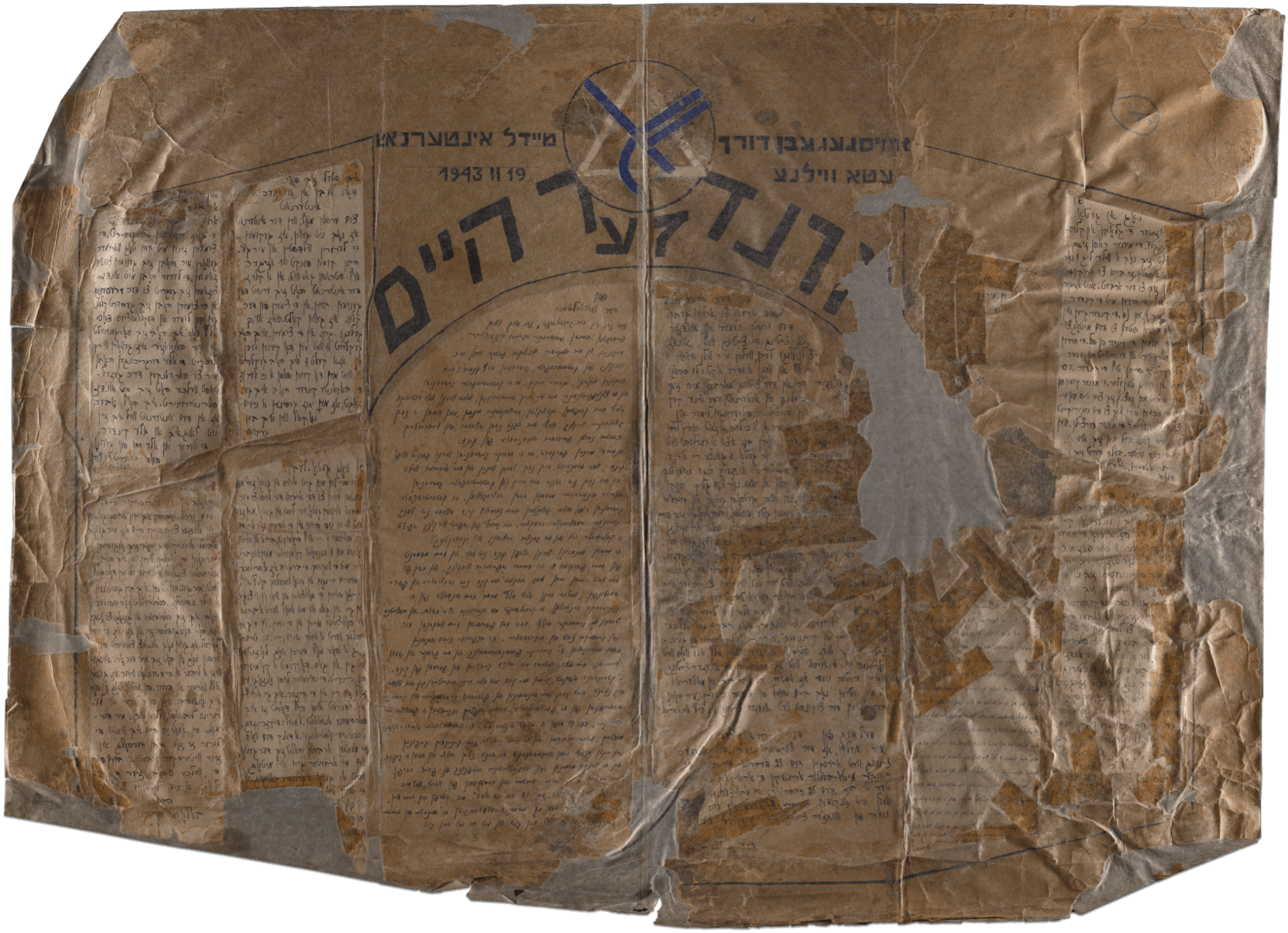

What was happening in the world?

In this section you will find headlines of newspapers showing what was happening in the world at the same time that we tell Yitskhok Rudashevski’s story, following the chapter’s timeline.

1941

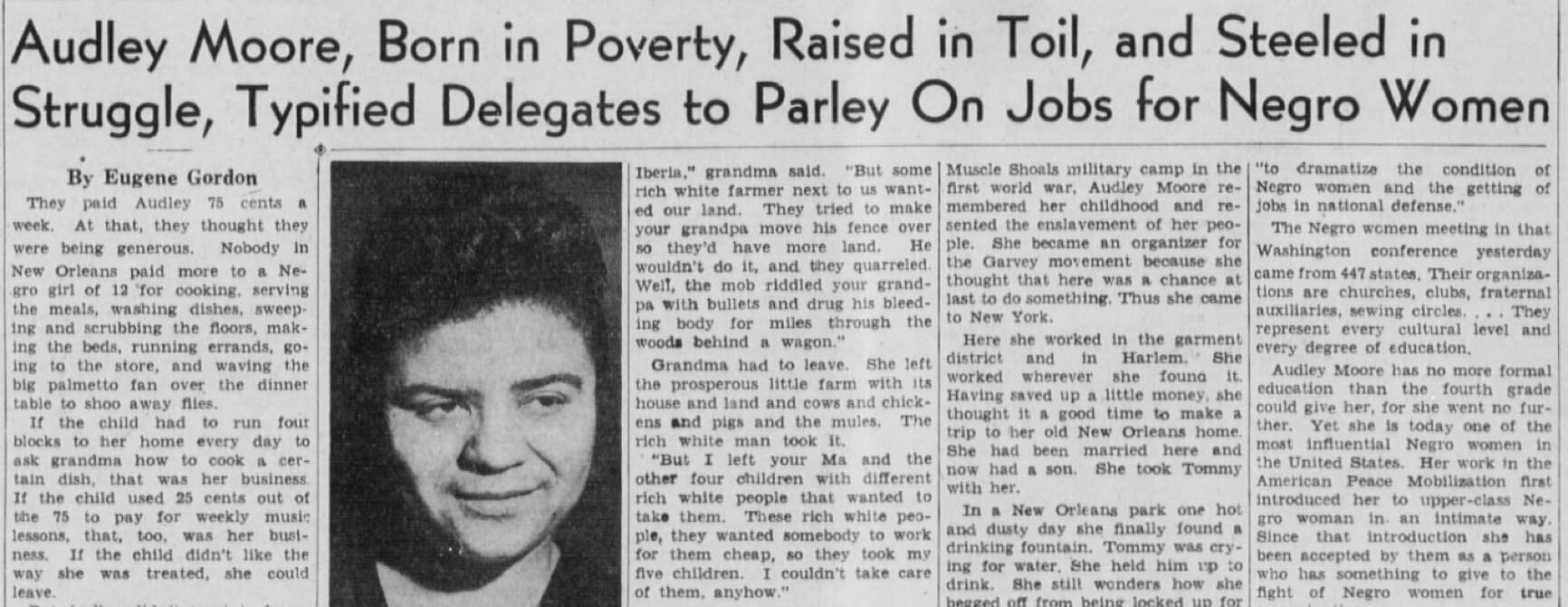

Brooklyn Eagle, June 23rd, 1941. Courtesy of the Brooklyn Public Library.

The Daily Worker, June 30th, 1941.

Source: Marxists Internet Archive.

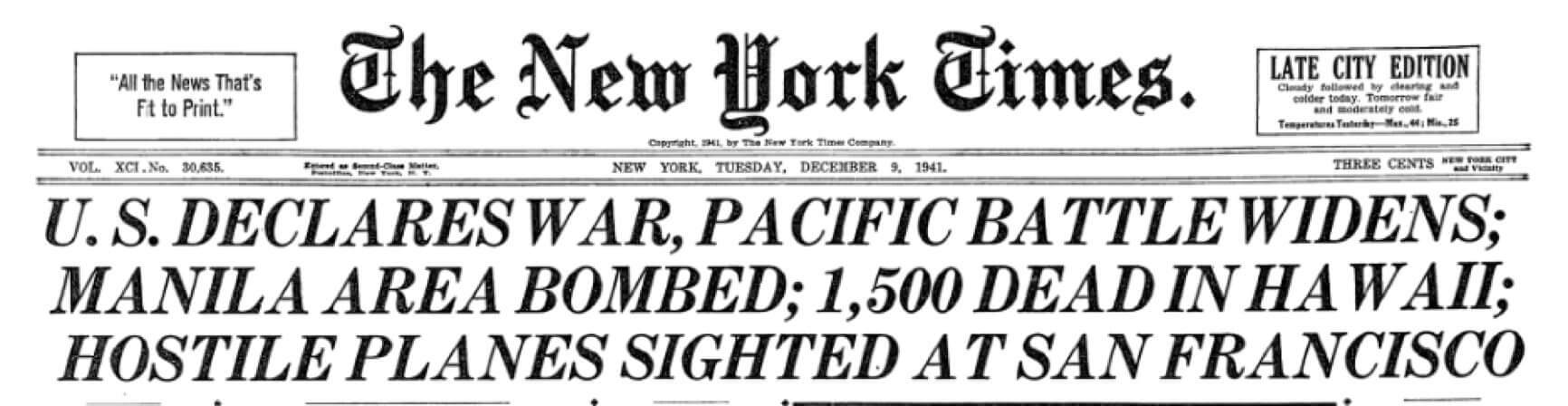

New York Times, December 9th, 1941. Courtesy of The New York Times.

1942

New York Times, May 16th, 1942. Courtesy of The New York Times.

Wannsee Conference held to discuss the “Final Solution”

A school system was quickly established throughout the Vilna ghetto. Students of all ages were able to study secular, religious, vocational, and artistic subjects in dedicated spaces. Education provided hope in even the most desperate days in the ghetto, distracting students from their suffering and offering them a way to think positively and plan for a future after the war. Here, you’ll find artifacts related to schools in the Vilna Ghetto.

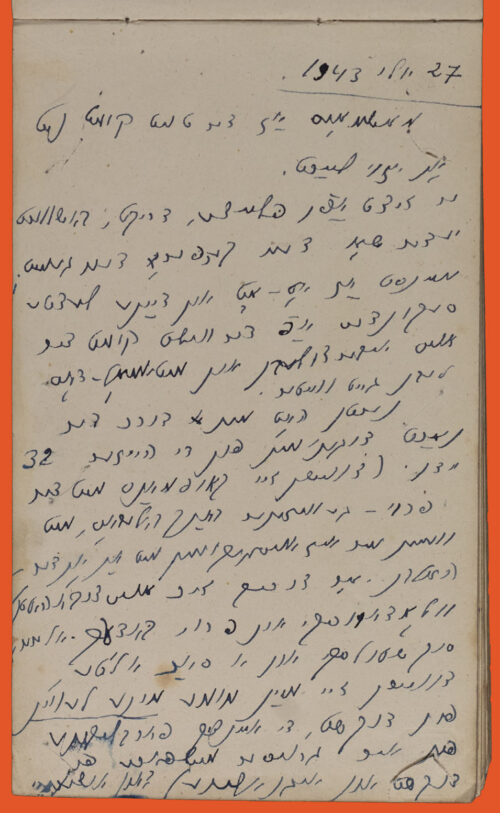

"The days go by quickly. I did my various assignments, occupied myself a bit with housekeeping. Read a short book, wrote in my diary and off to class. The classes went by fast: Latin, Mathematics, History, Yiddish – then back home, had a bite to eat and off to the Club. Here we enjoy ourselves a bit. Today there was an inspection led by Yashunski (the head of the Education Department). We also watched the Club’s Maydim (puppets) performed by two boys. It’s quite good, though pretty primitive. The literary side is very weak, but it doesn’t matter if we see creativity. Our youth is at work and is not going under. Our History circle is functioning. We hear lectures about the great French Revolution and its phases. The second branch of the History circle – ghetto history – is also at work. We are researching the courtyard at 4 Shavler Street. For that purpose questionnaires, with the questions to be posed to the ghetto-inhabitants, have been distributed among the members. We have already begun the work. I go with a friend. The questions are divided into four periods: questions dealing with the Poles, the Soviets, the Germans (before the ghetto), and in the ghetto. The inhabitants answer in different ways, but everywhere it is the same tragic ghetto-refrain – possessions, certificates, malines, loss of property, loss of loved ones. I have tasted the work of the historian. I sit at the table and ask questions and write down the immense griefs dryly, factually. I write, I immerse myself in details and do not realize that I am immersing myself in wounds. And what answers people casually give me: They took away two sons and a husband. The sons on Monday, the husband Thursday. And this horror, this tragedy, is formulated by me in three words, coldly and drily. I ponder this and the words look up at me with flame and blood…"

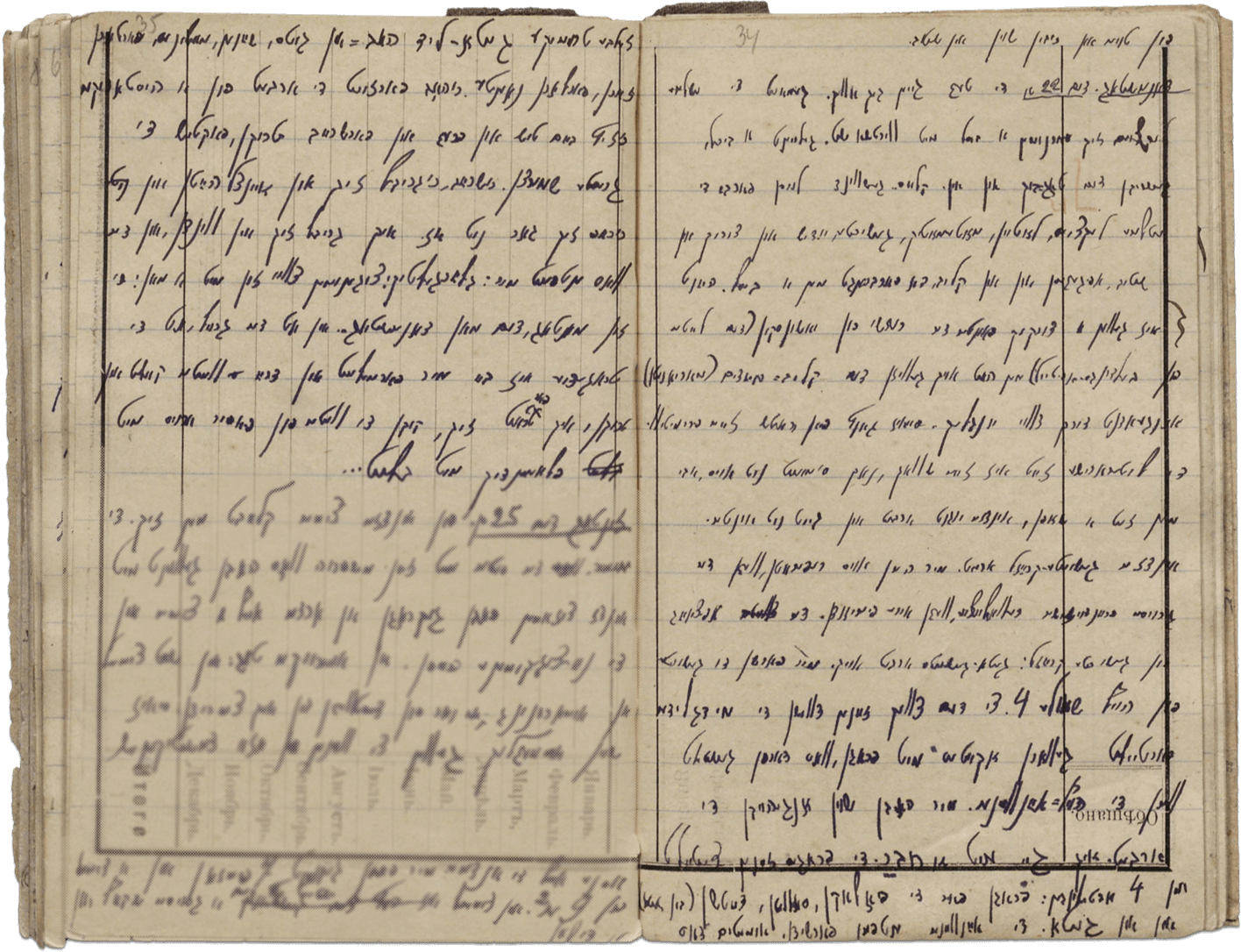

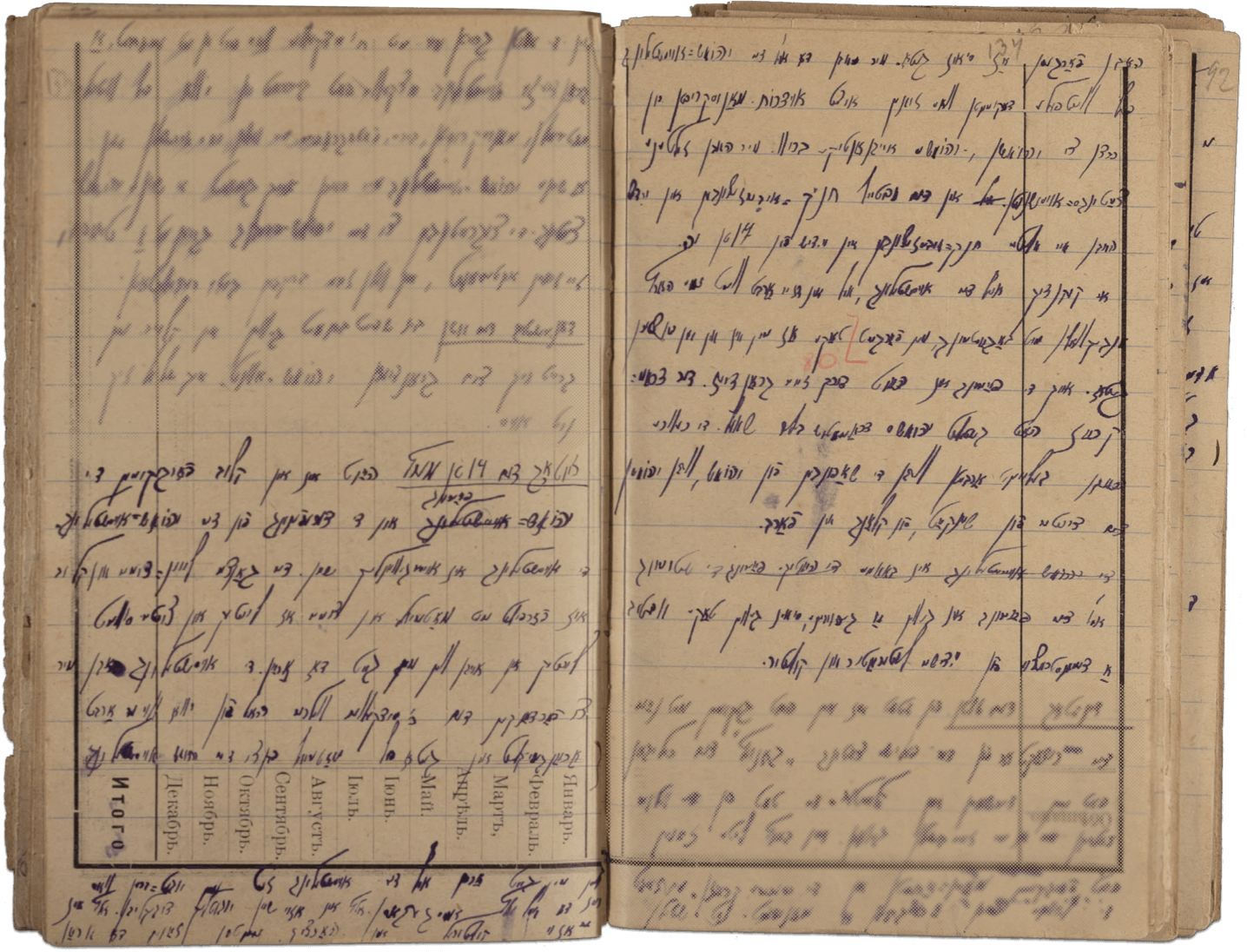

Notes by M. Kharash, a teacher in Vilna, on Tacitus and the Jews, possibly for use in lectures. The text switches between Polish, German, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew.

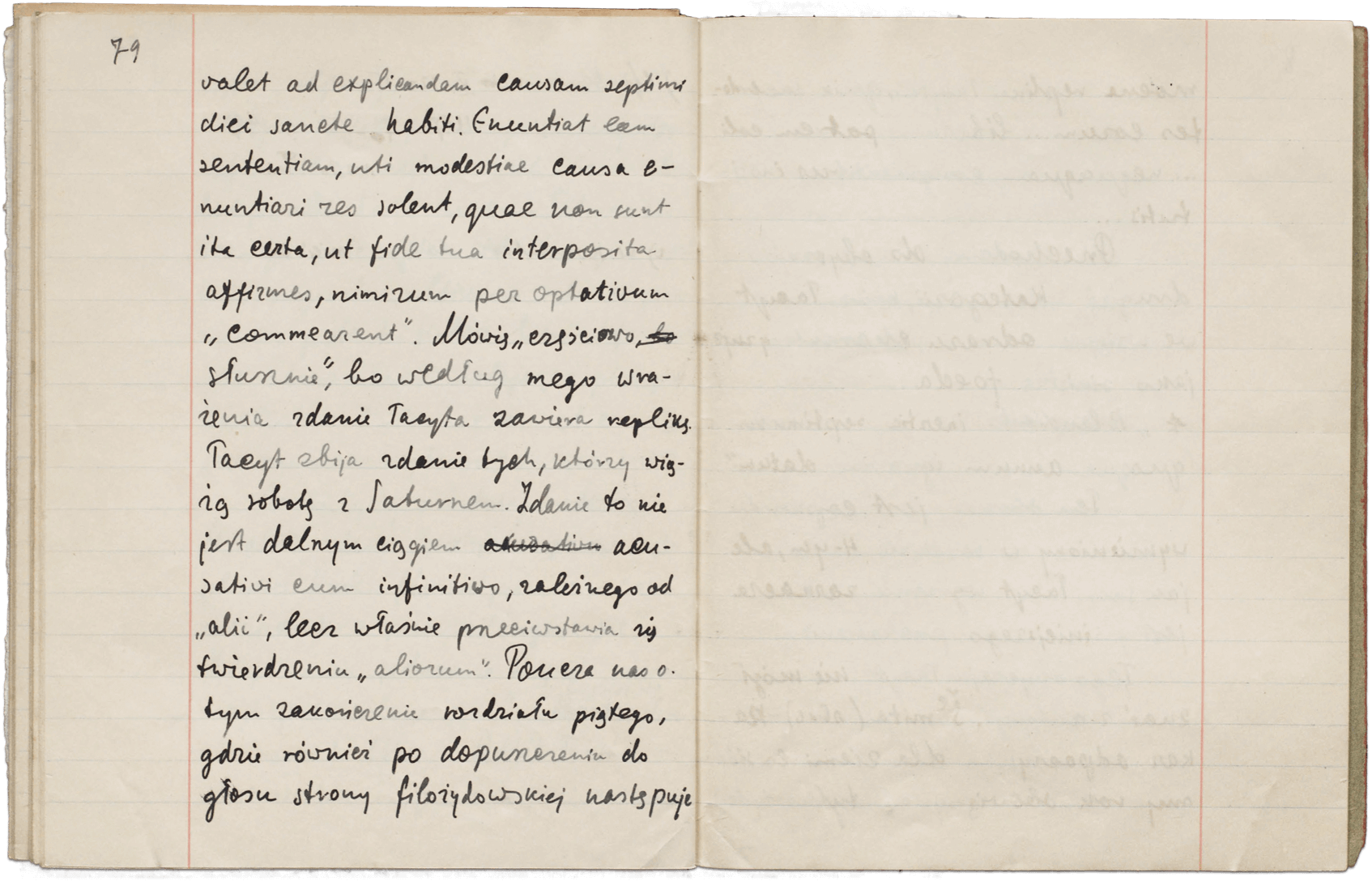

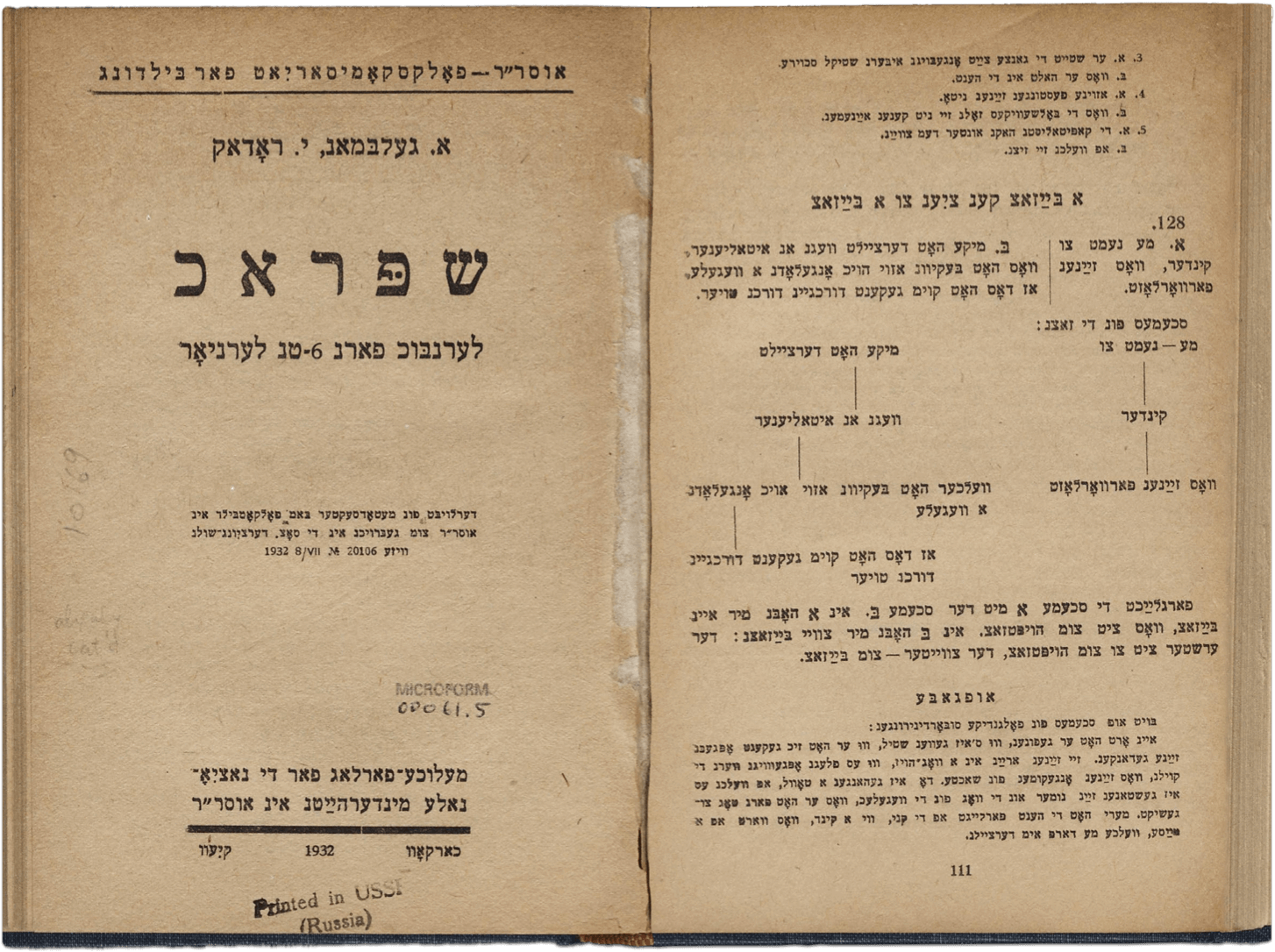

A math textbook. This page deals with division into thirds, adding and subtracting fractions, and multiplication by six. Soviet texts were introduced in Vilna Yiddish schools in 1940.

A ten-volume account of Jewish history written by Simon Dubnow, a famous Russian-Jewish historian, activist, and advocate for Jewish education. The tone is densely academic.

A Yiddish textbook for Yiddish-speaking students. This book contains exercises including reading newspaper articles, correcting poetry, finding synonyms, and writing dialogues.

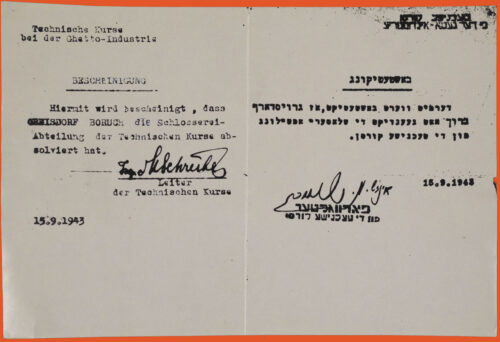

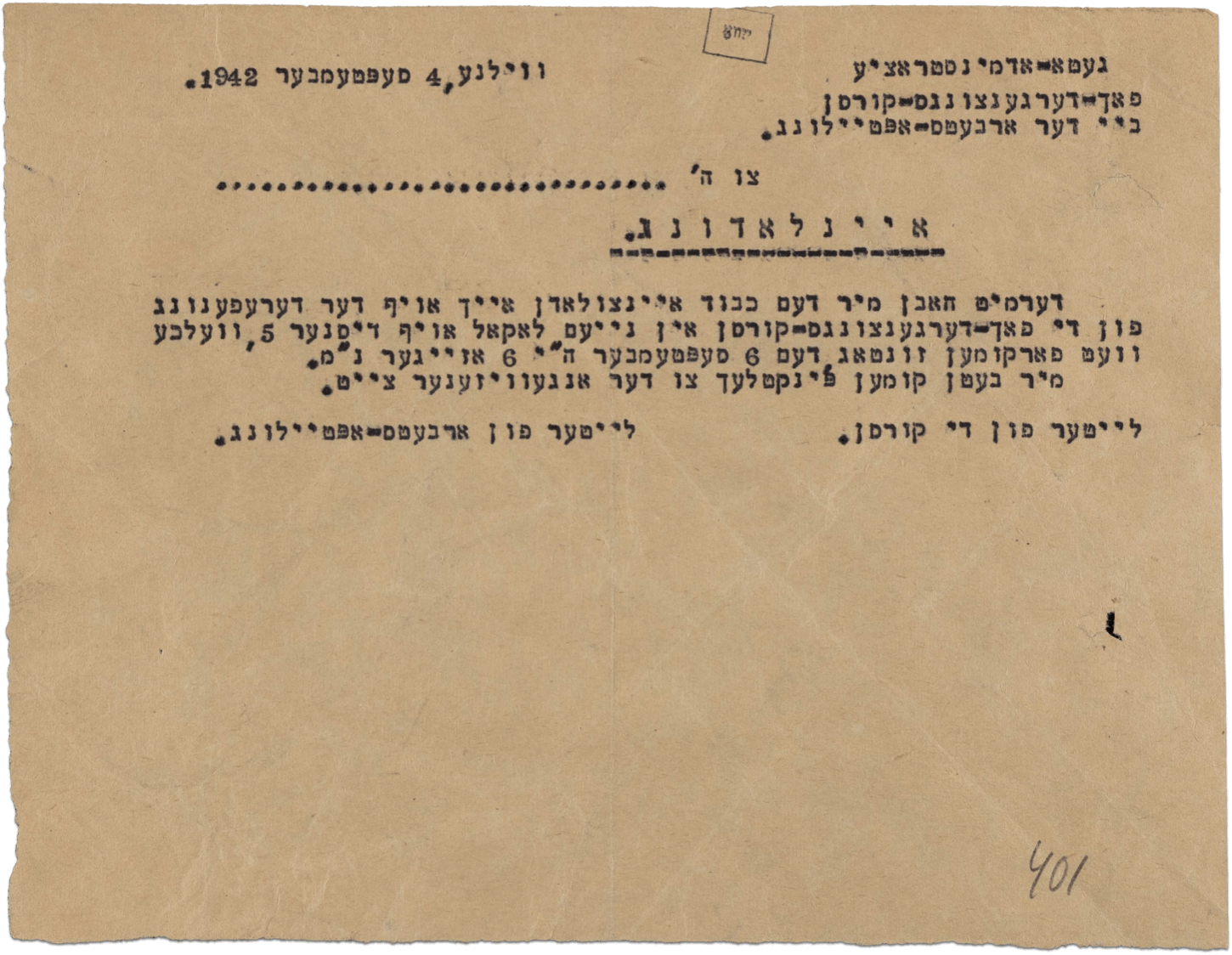

Invitation to inauguration of the new premises of the Ghetto Vocational Courses on September 6th, 1942.

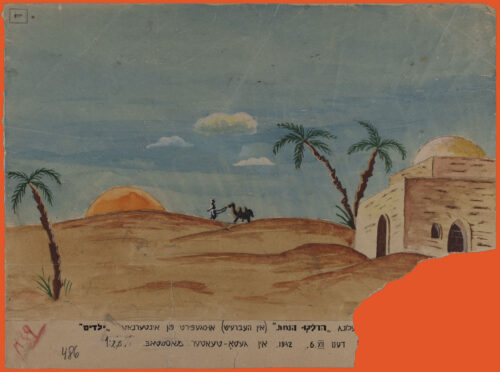

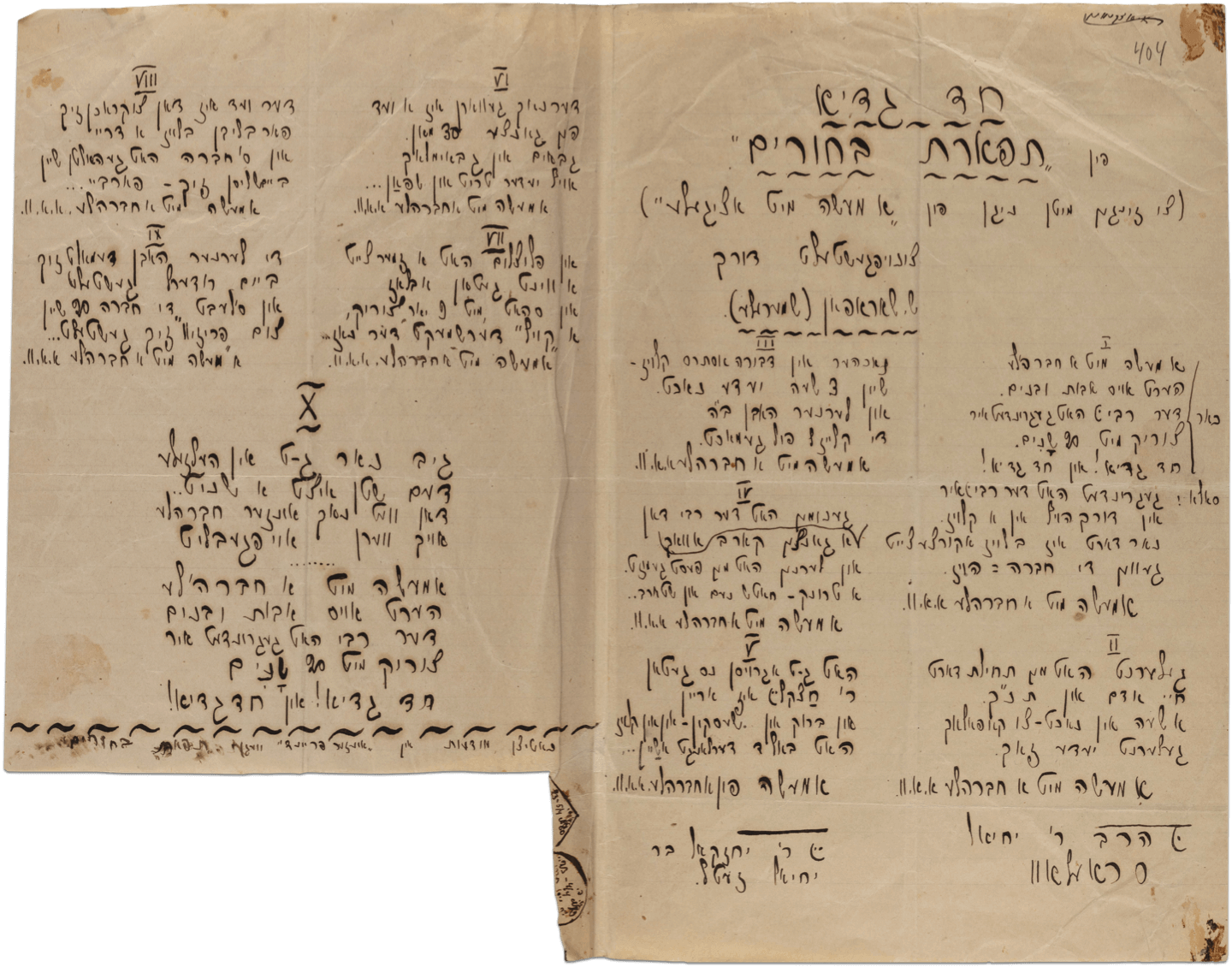

“Had Gadya” is the name of a song typically sung at Passover, and is often adapted into different, usually humorous, interpretations. This is a Yiddish parody of the original.

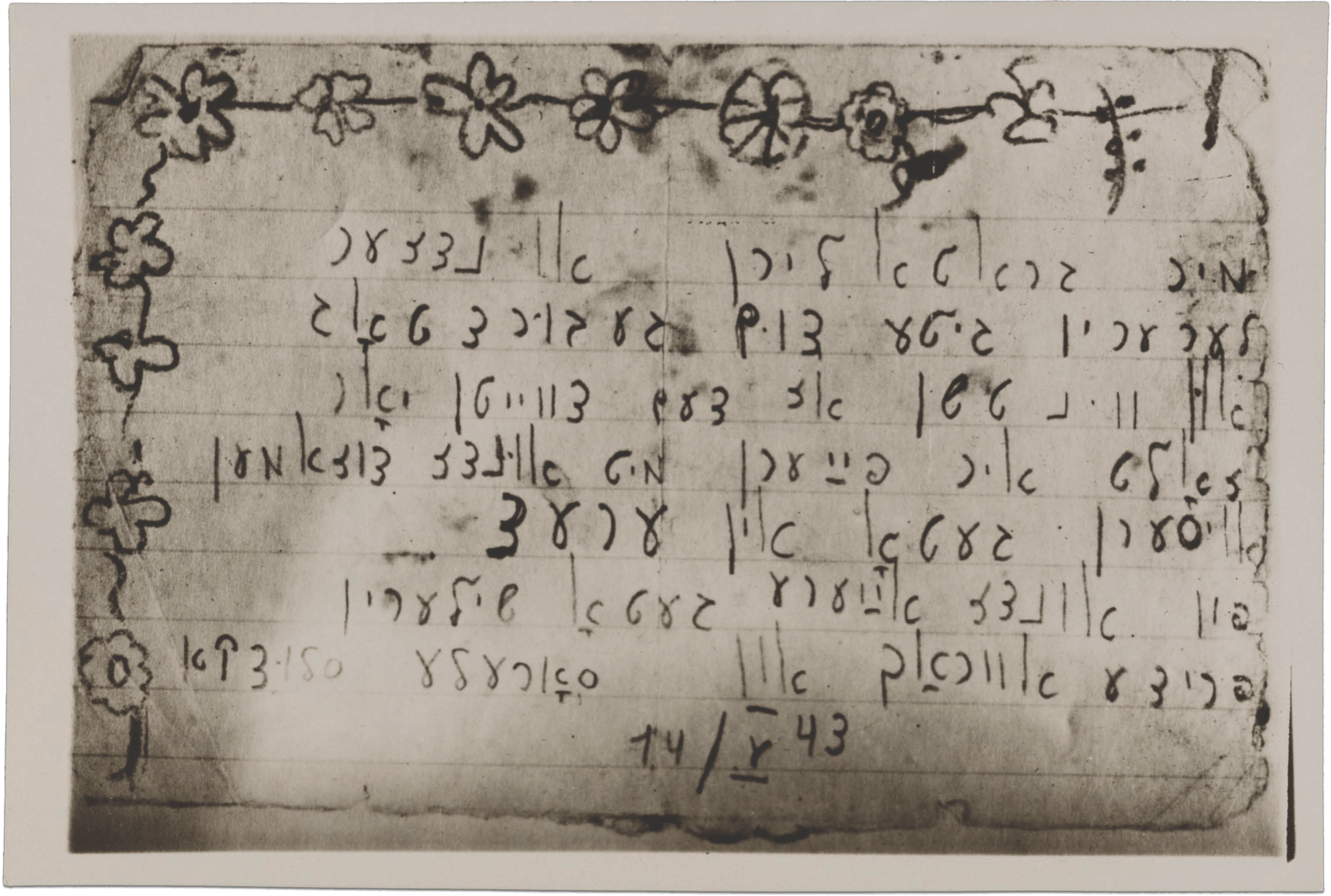

The greeting reads: “We congratulate our teacher Gita for her birthday and wish that the second grade should celebrate her together with us outside of the ghetto in the Land (of Israel). From us, your ghetto students, Fride Avram and Sorele Slutska.”

This wall newspaper, titled Undzer Heym (Our Home), is about the day-to-day lives of the girls living in the dormitory.

“It is cold in the rooms of the synagogue. There is also debris in the rooms. I asked, how can one live in such cold? How can one build a new life?”

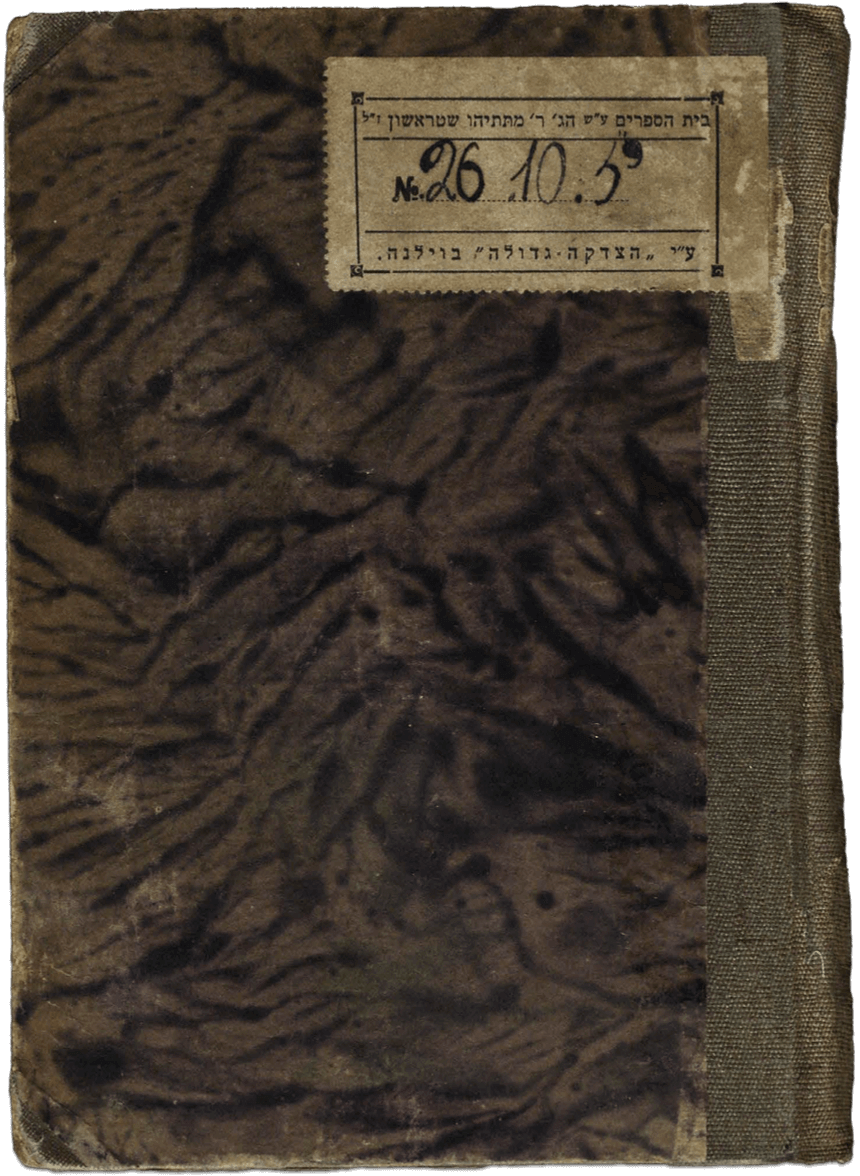

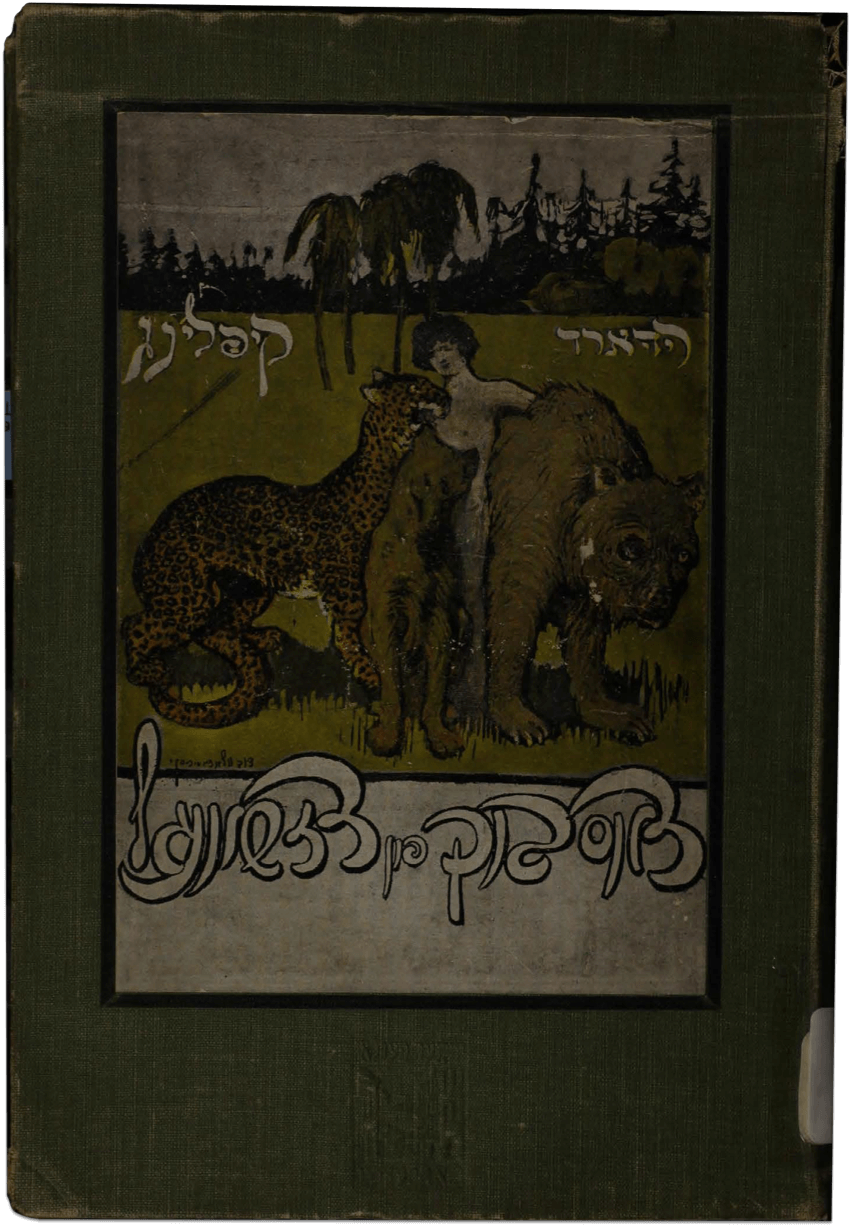

This children’s book by revered Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem (pseudonym of Sholem Rabinovitsh) follows the antics of a young boy living in a shtetl following the death of his father. The novel was published in two volumes, though the second volume was unfinished at the time of Aleichem’s death. This artifact is from the Strashun Library, a famous Jewish library in Vilna. Some of its looted collection was sent to YIVO after World War II.

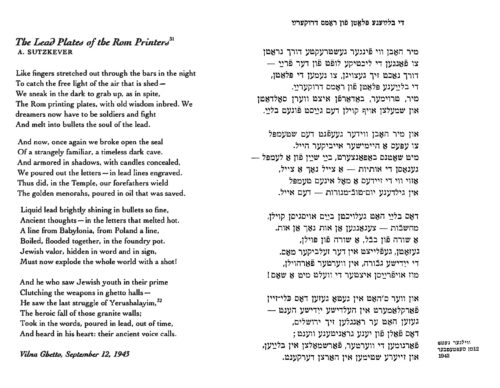

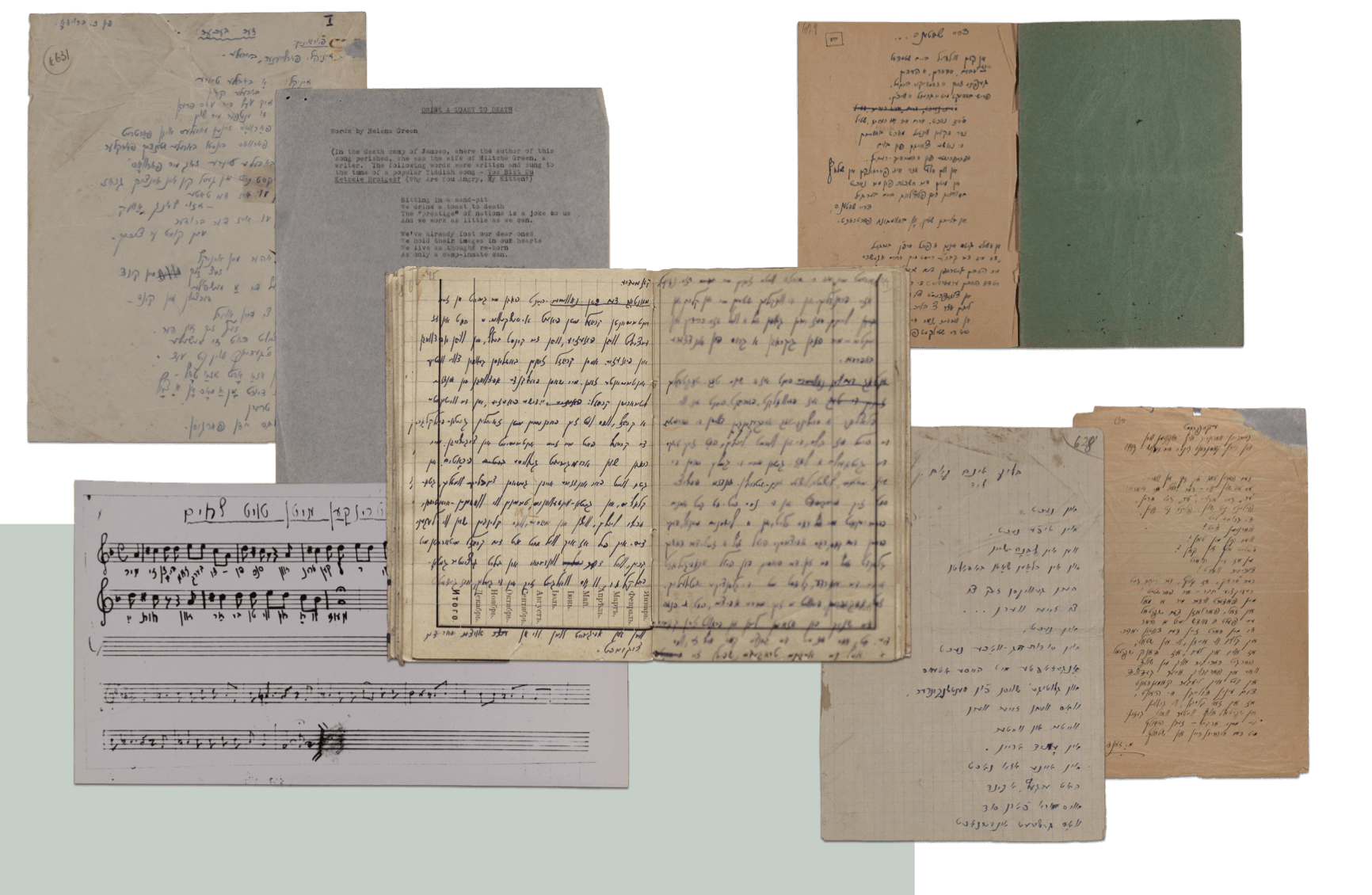

Groups that focused on different interests met regularly in the ghetto, some led by prominent figures who served as mentors. One of those was Avrom Sutzkever, a famous Yiddish poet who later became a partisan in the Vilna area. At that time, partisans were members of armed groups created to secretly fight against occupying forces. Sutzkever was an important mentor for Rudashevski in the literary club. In the ghetto, Sutzkever was enlisted by the Nazis to curate important looted Jewish artifacts so that the Nazis could display them after putting an end to Jewish life in Europe. Sutzkever performed this job under penalty of death, while also working to smuggle many of these important artifacts and documents out of the hands of the Nazis. Sutzkever, along with other colleagues, formed a group known as the Paper Brigade, and were able to save a large collection of materials that were later sent to YIVO in New York City, where the materials remain to this day. Here, you’ll find creative writing from Sutzkever and others, written in the ghetto.

"Today our circle had a very interesting meeting with the poet A. Sutzkever. He spoke to us about poetry, about the art of poetry in general and about the varieties of poetry. At the meeting, two important and interesting things were decided. We are creating the following branches of our literary circle: Yiddish poetry, and most important, a group to concern itself with ghetto-folklore. I was very interested in, and attracted to, this circle. We have already discussed certain details. In the ghetto, before our own eyes, dozens of sayings, curses, good wishes and terms like vashenen – smuggle in – are being created, even songs, jokes and stories that already sound like legends. I feel that I will participate in the circle enthusiastically, because the wonderful ghetto-folklore, etched in blood, which abounds in the streets, must be collected and preserved as a treasure for the future."

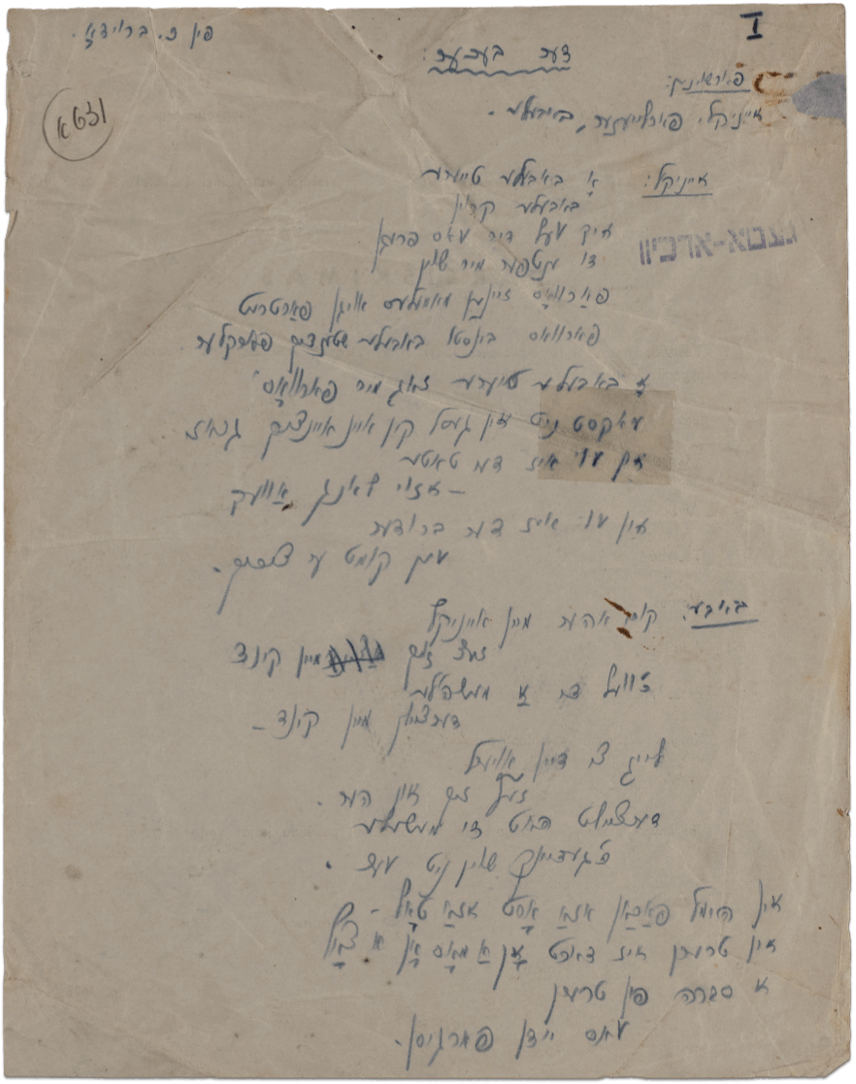

“Der Bekher” (“The Goblet”) is a number from a musical play by K. Broido, a popular composer in the Vilna Ghetto. In it, a child asks his grandmother where his parents are, and the goblet refers to all the Jewish tears.

The "three shadows" refer to the dead at the Ponar forest.

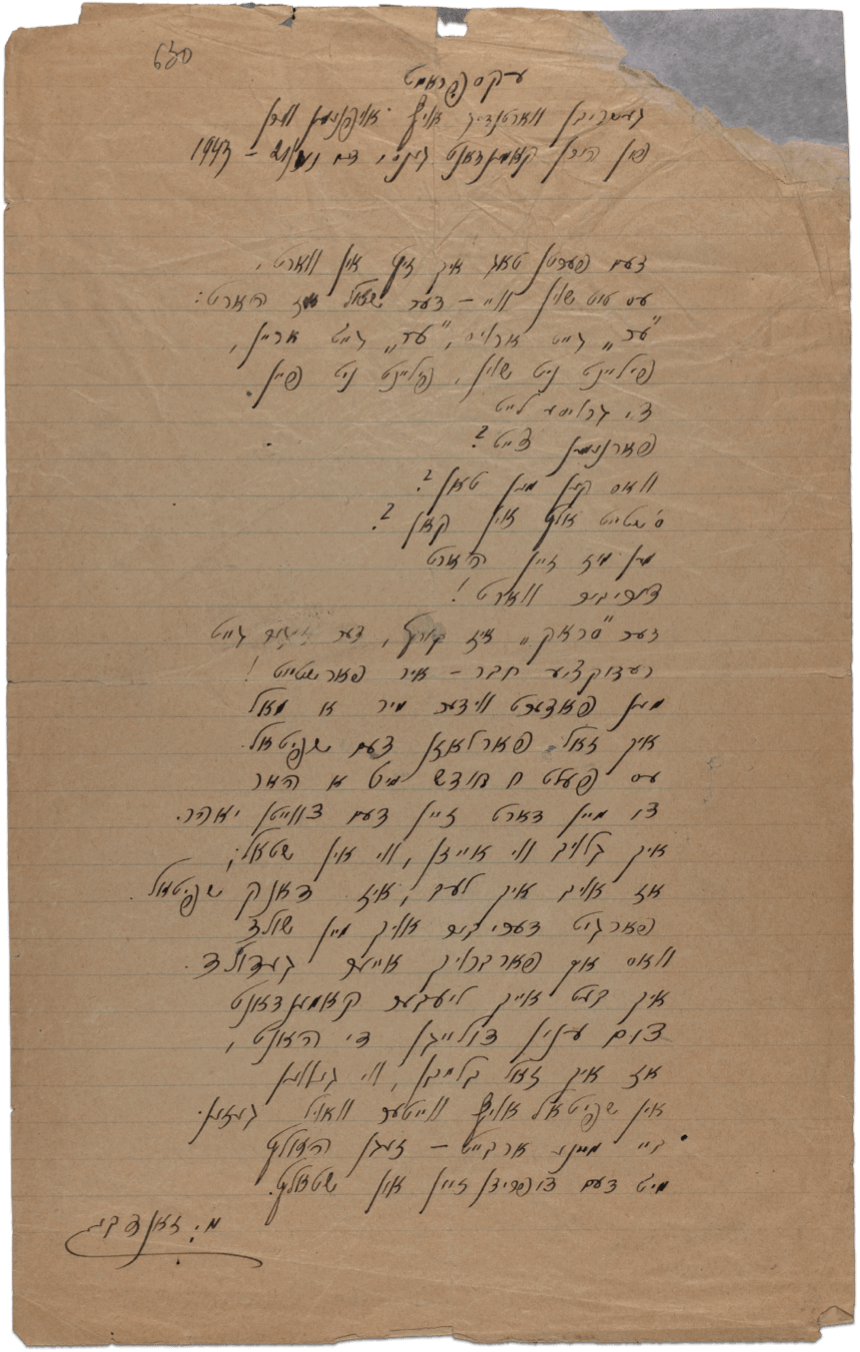

This poem was written while the author was in a long wait to meet with Jacob Gens, the commander of the Jewish police in the Vilna Ghetto, to ask for permission to remain in the Ghetto Hospital. Dated June 21st, 1943.

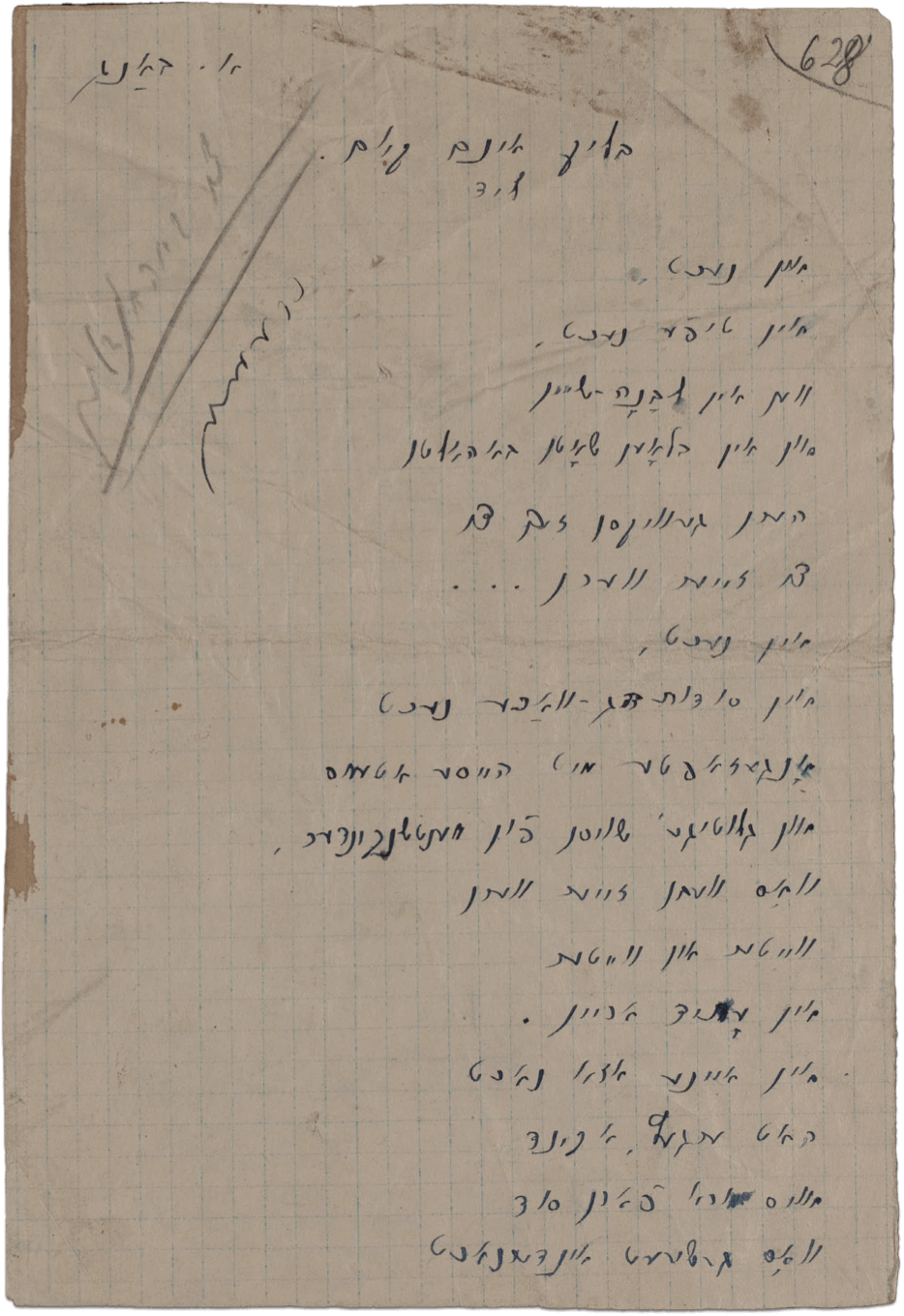

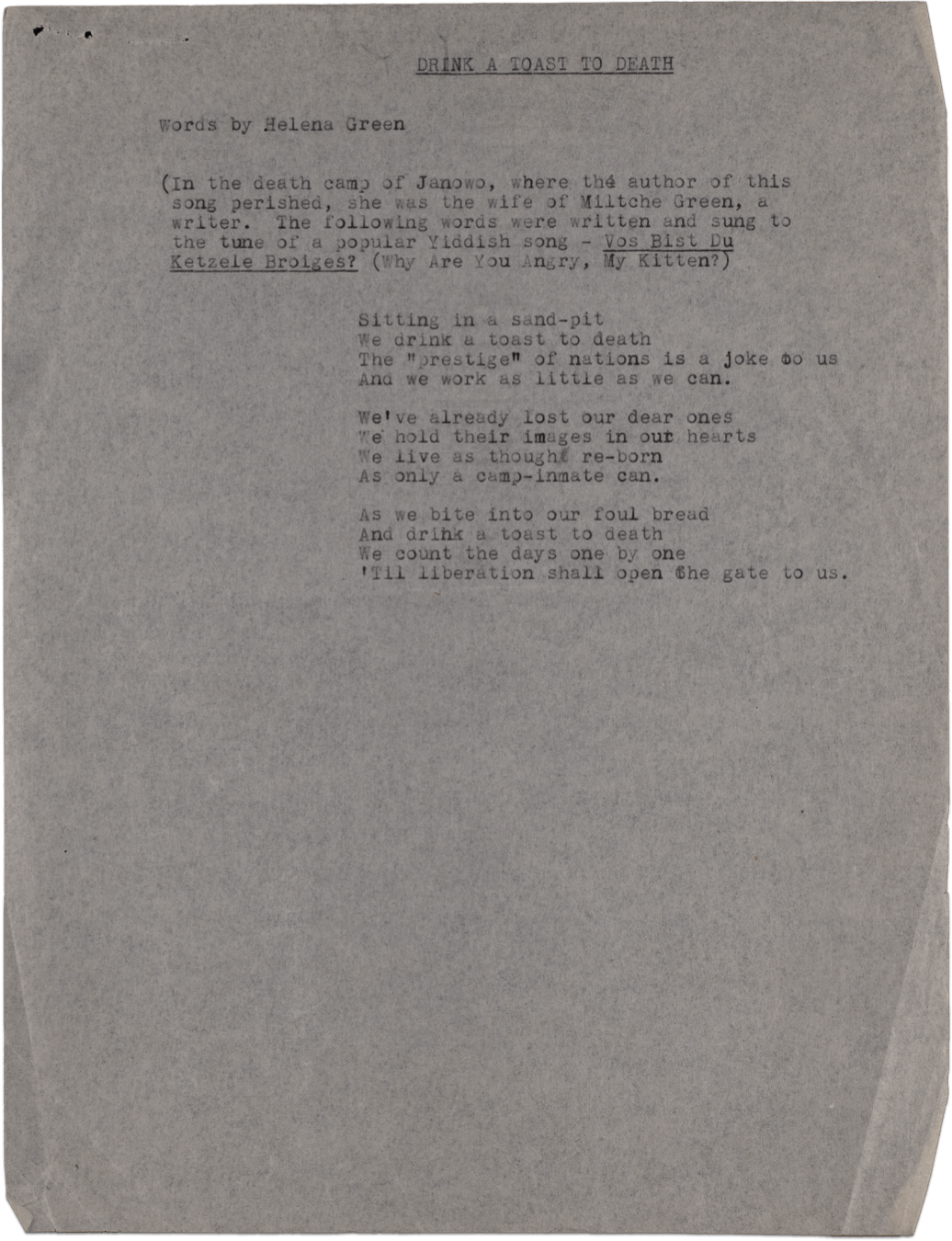

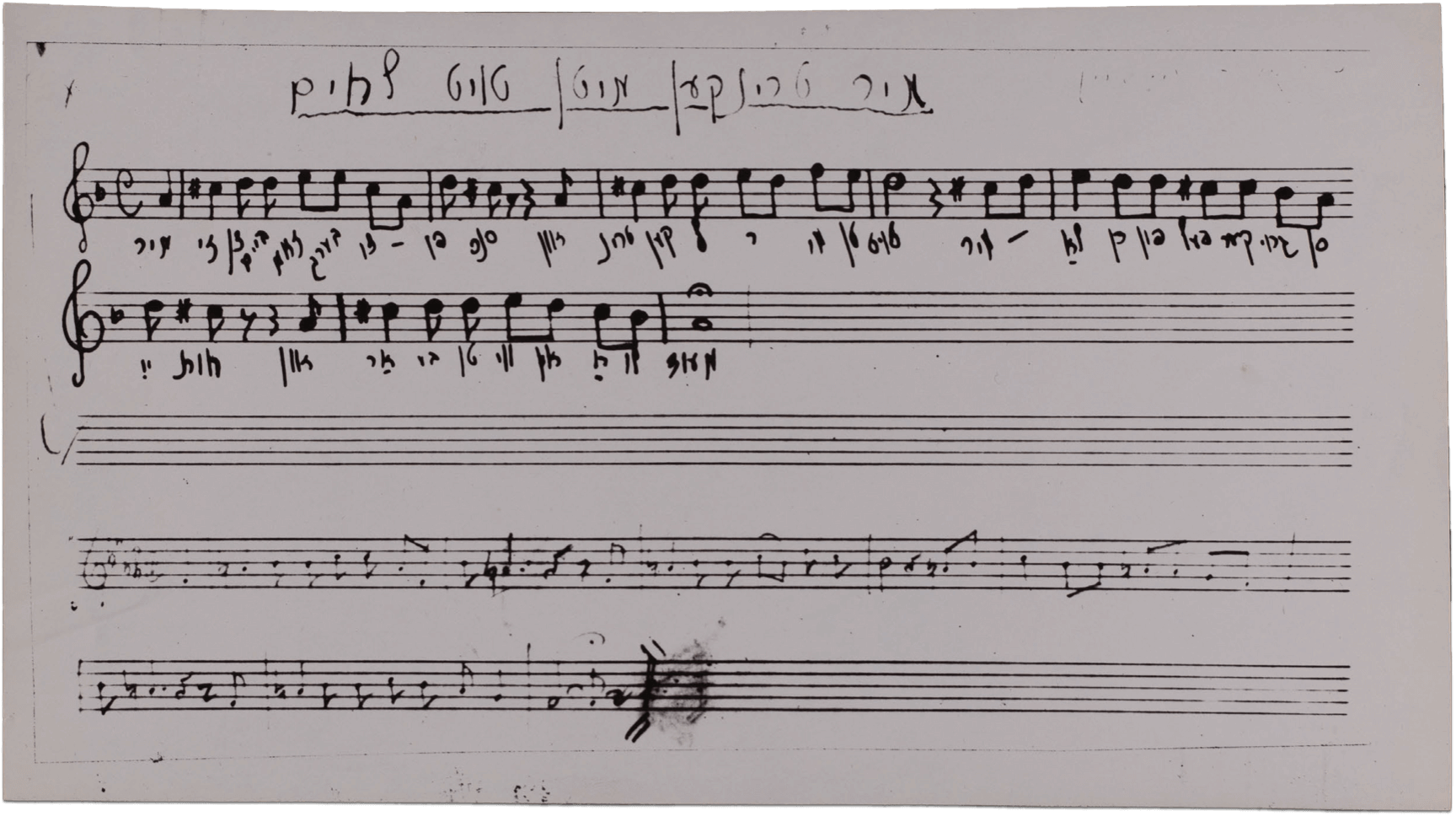

English lyrics and description of the song, which was written in a concentration camp by Helena Green and transcribed by Shmerke Kaczerginski after the war.

Sheet music and lyrics to the song, which was written in a concentration camp by Helena Green and transcribed by Shmerke Kaczerginski after the war.

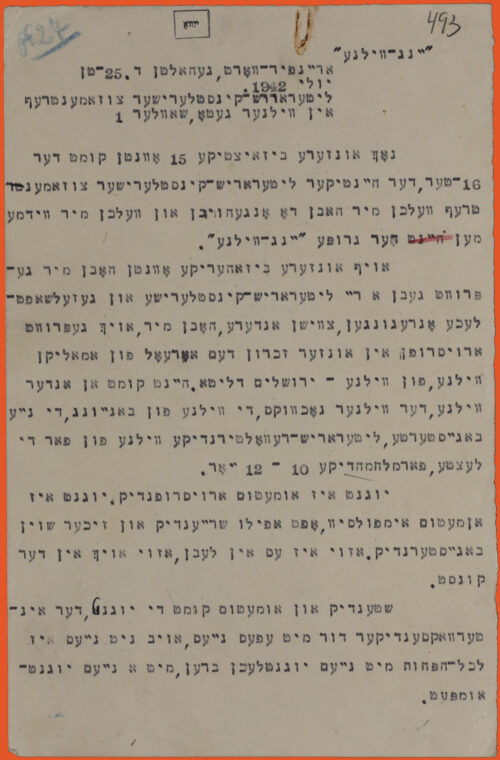

Rudashevski, like many other children in the ghetto, was active in the ghetto’s Youth Club. Teachers from the ghetto schools led the activities of the club, which were divided into sections focusing on the arts and culture. Rudashevski was deeply involved in the club, taking part in the history, nature, and literary divisions. He also watched the auditions and performances of the drama division. Rudashevski and his cousin, Sore Voloshin, were both part of what Rudashevski called the “P-Project,” a division of the club run by the partisans oriented towards acts of resistance against the Nazis. Here, you’ll find artifacts related to the Vilna Ghetto Youth Club.

“Today at our house they built a range. By chance, the electricity was cut off. They work on the range by candlelight. The room is full of clay and bricks. And in the middle of the commotion there’s me with my scribbling. Lately I have a mass of work from school and the Club. I spend whole days with history books. We are preparing various reports and trials. In addition, I am in charge of the circle for creative original writing with the poet Sutskever, and I have to be in constant contact with him. The study period in the morning is quite agreeable, but the rest of the day rushes past quickly. I don’t even have time to finish my book from the library. I have presentation after presentation in Yiddish and History to worry about. And it’s all happening at the same time. Every evening, as usual, I go to the Club, visit the history circles, the nature circle and the literary ones. I often stay for the tryouts of the dramatic circle – it’s happy, cheerful. We wait impatiently for the completion of our space on Disner Street.”

Danton: Drama in Three Acts from the French Revolution is a three-act play by Romain Rolland about the events of the French Revolution.

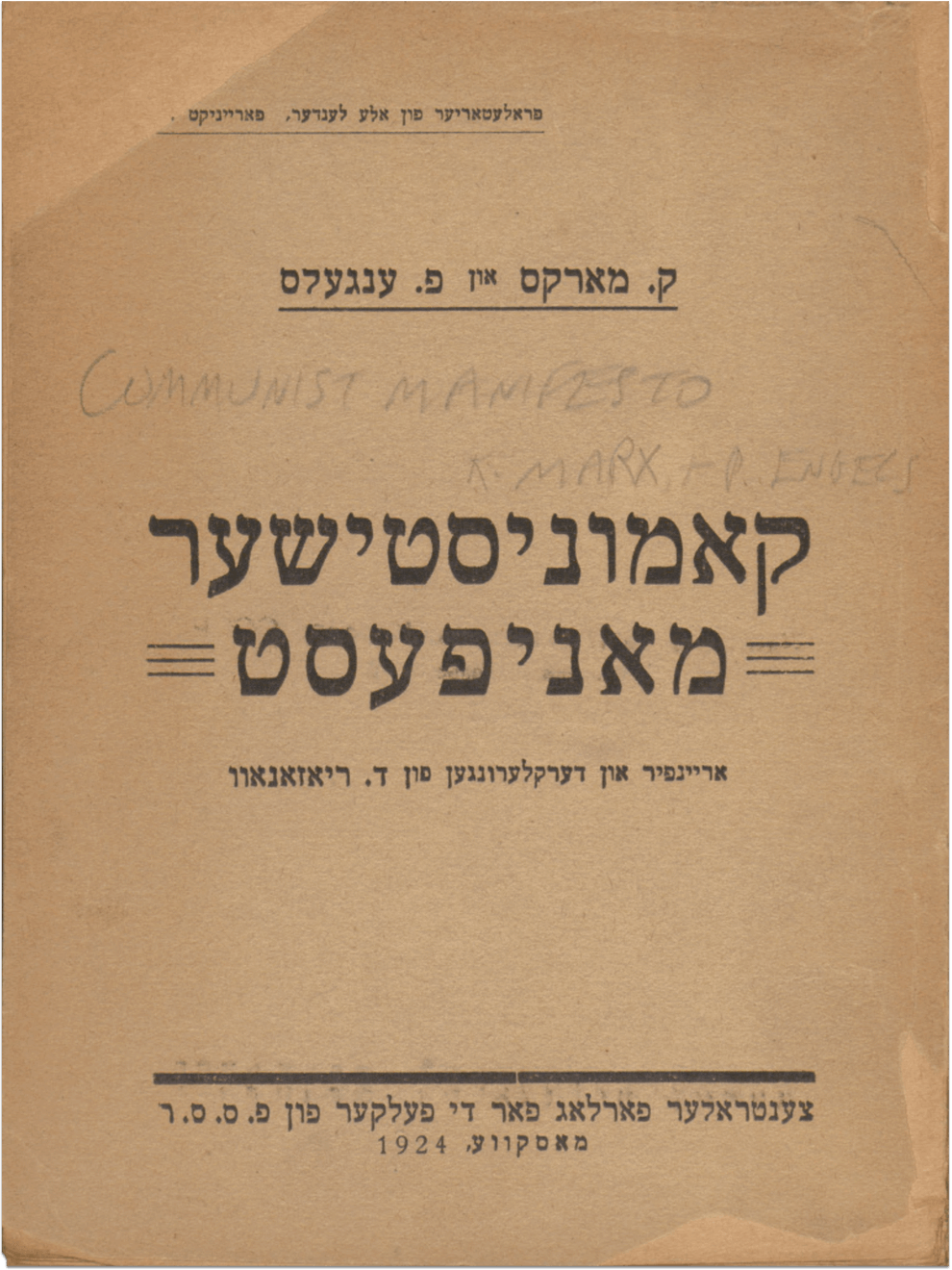

History of the Workers’ Movement: The Great French Revolution is a history of the French Revolution written from an explicitly Marxist perspective. Given Rudashevski’s identification as a communist, his studies of history and revolution likely were related to his interest in class struggle.

While this book is written with old-fashioned Yiddish spelling, this is another example of a Yiddish text about the Marxist history of the French Revolution. For Rudashevski, learning history – especially while living in the ghetto – was an inherently political and revolutionary act.

This is a Yiddish text about Marie Antoinette.

Rudashevski was interested in political theory as well as literature and likely read pamphlets and communist texts as part of his studies.

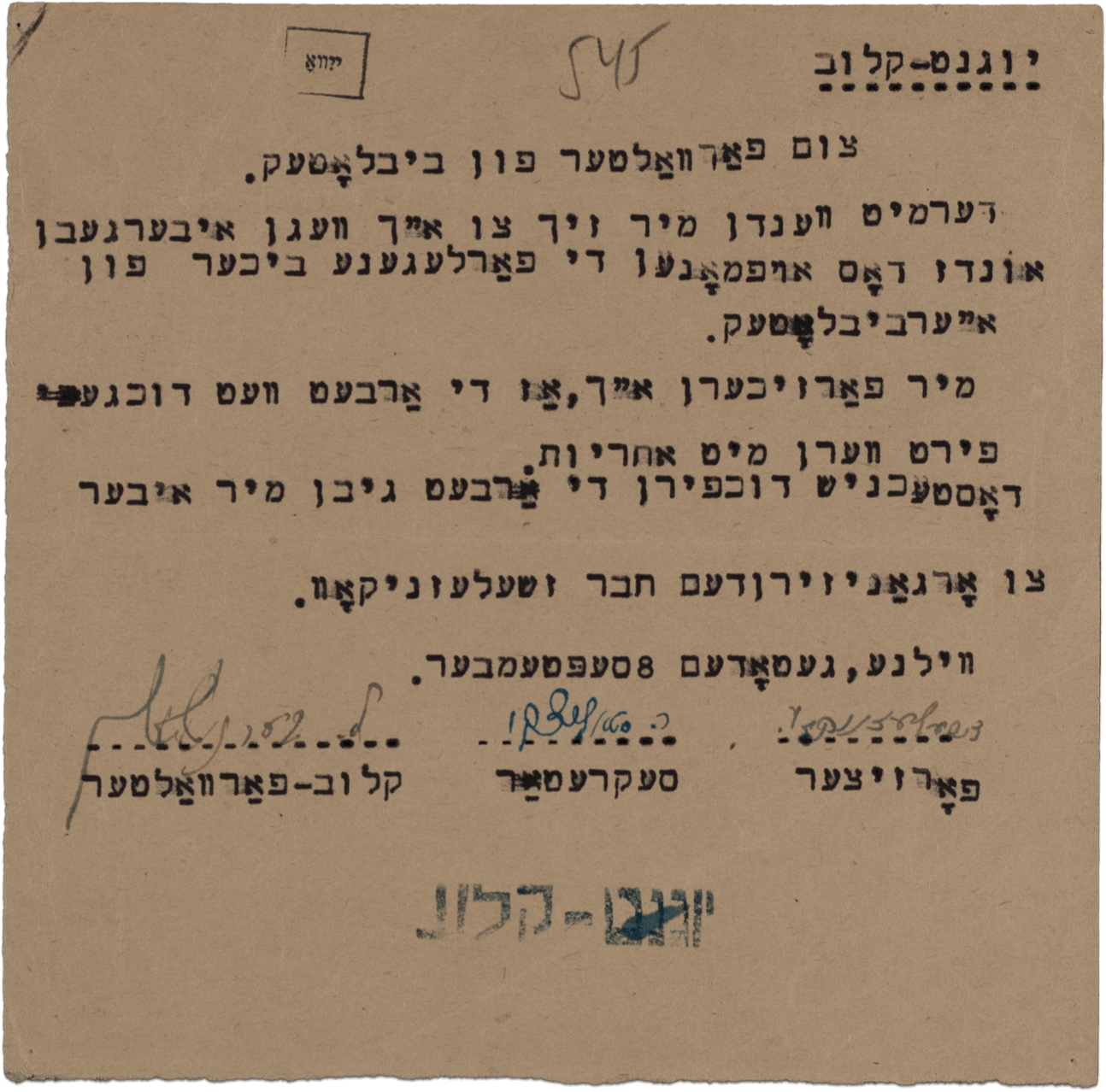

In this letter, members of the Youth Club ask the administrators of the ghetto library to allow them to take on library work, including collecting abandoned books. The members of the Youth Club wanted to be integral to the fabric of ghetto life, even when that meant taking on work originally meant for adults. Rudashevski was an active member of the Youth Club.

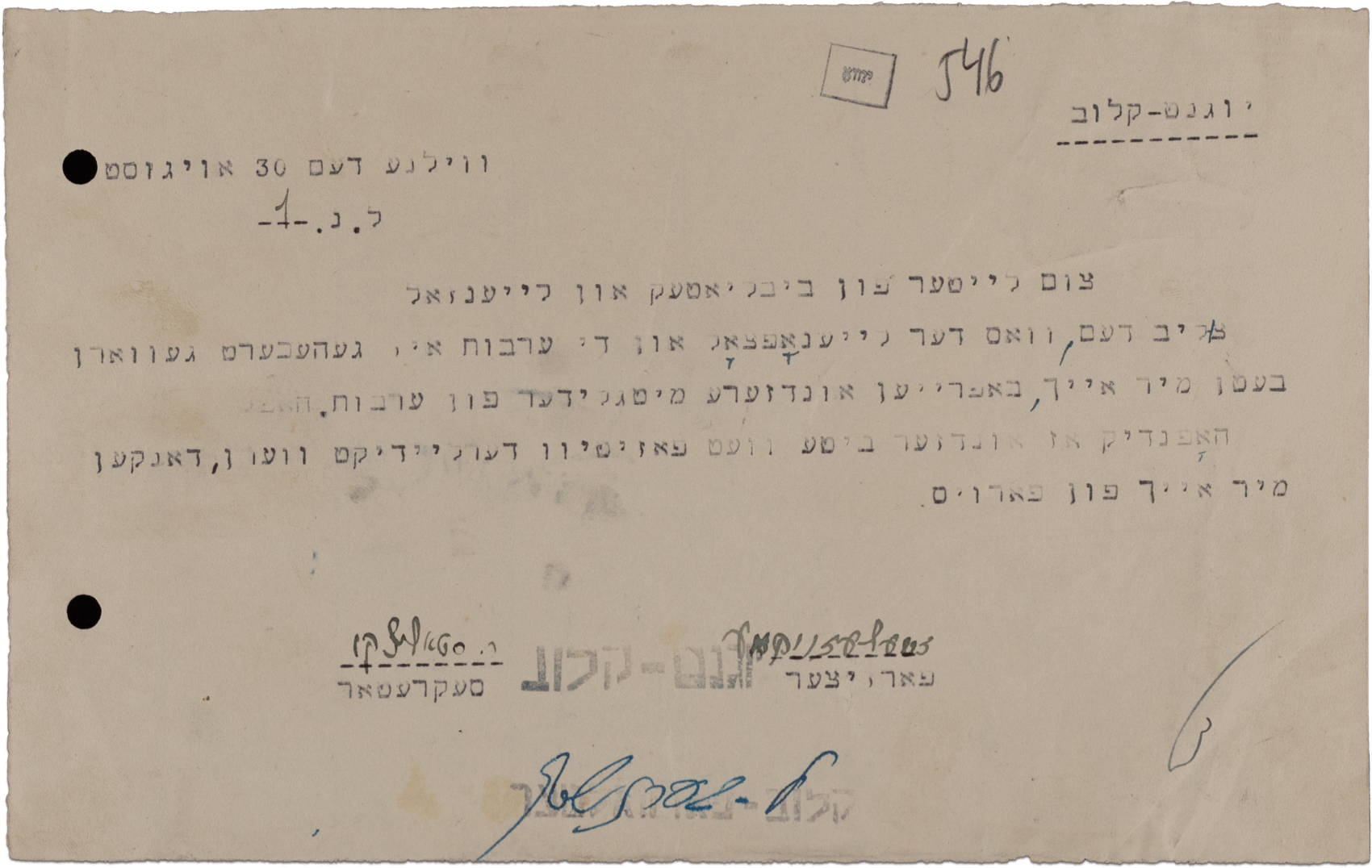

An appeal by the Youth Club to the head of the ghetto library for their members to be exempted from the security deposit to access the reading room. Members of the Youth Club yearned for learning and culture and sought to eliminate any barriers to library access for their members. Rudashevski was an active member of the Youth Club.

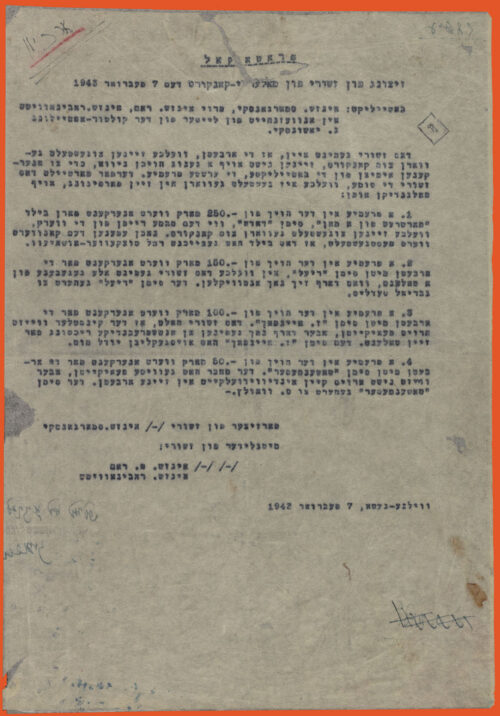

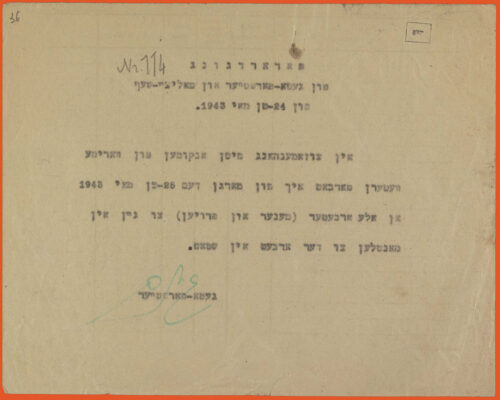

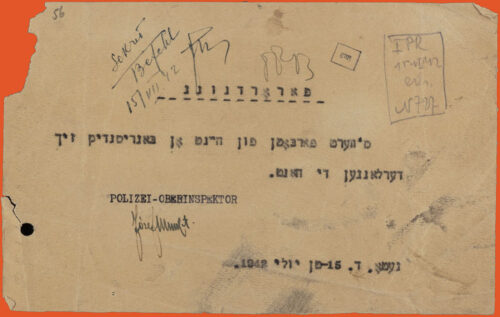

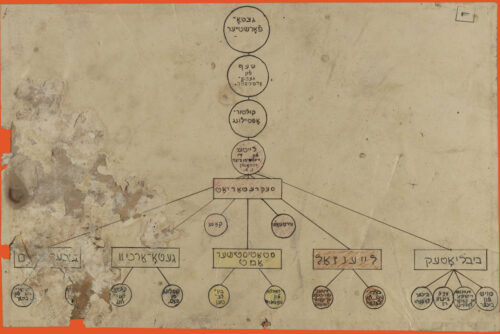

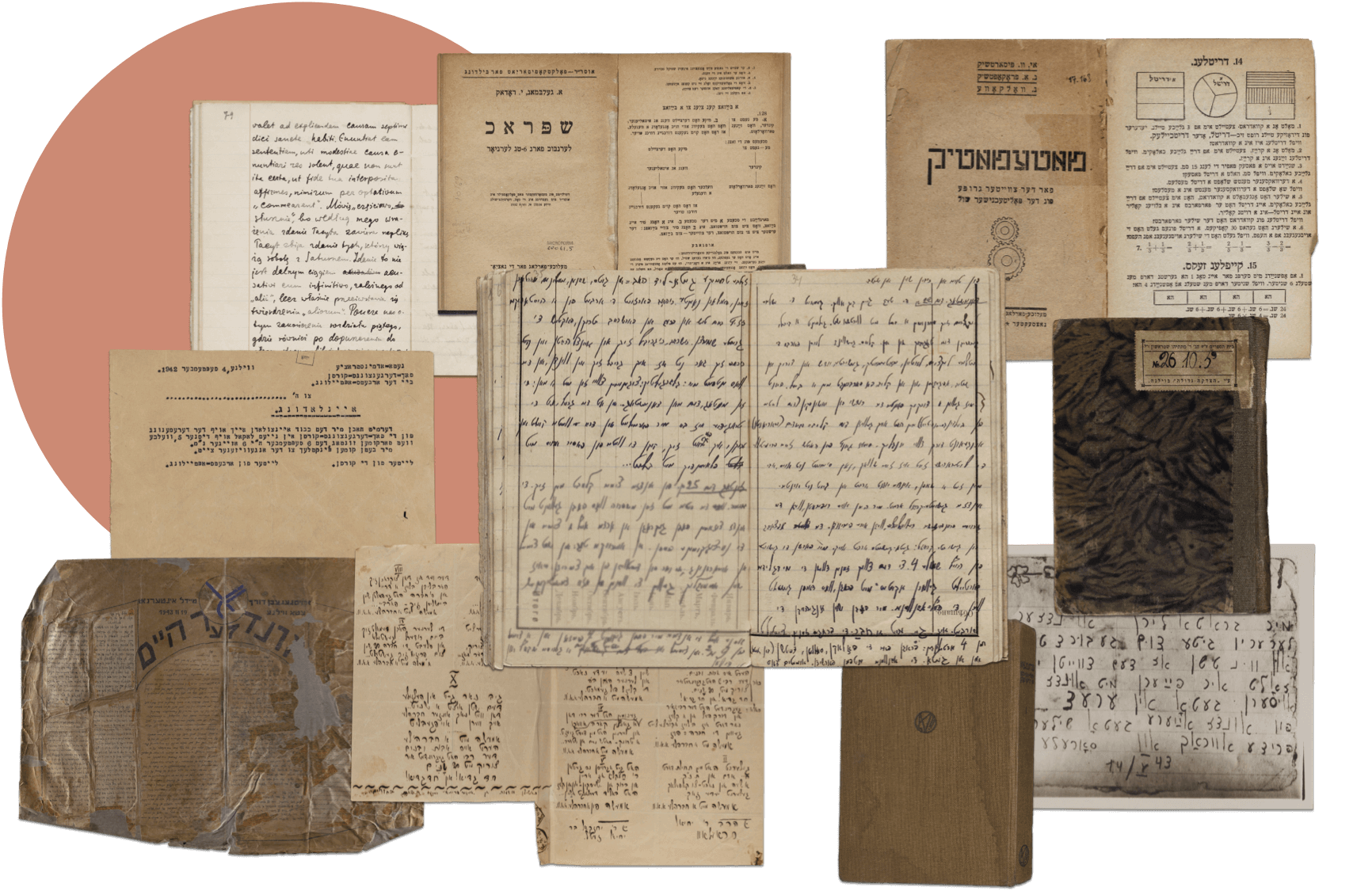

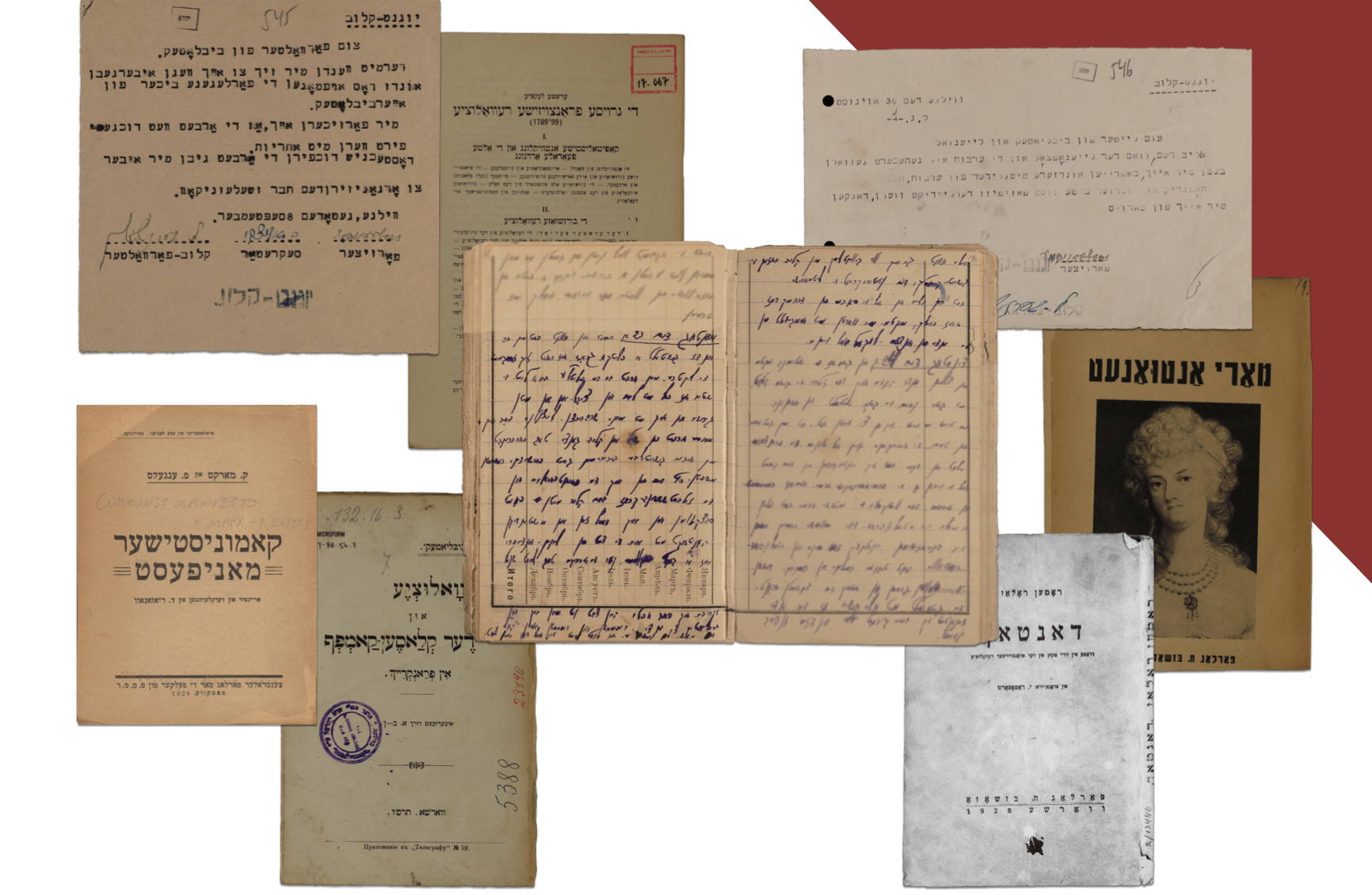

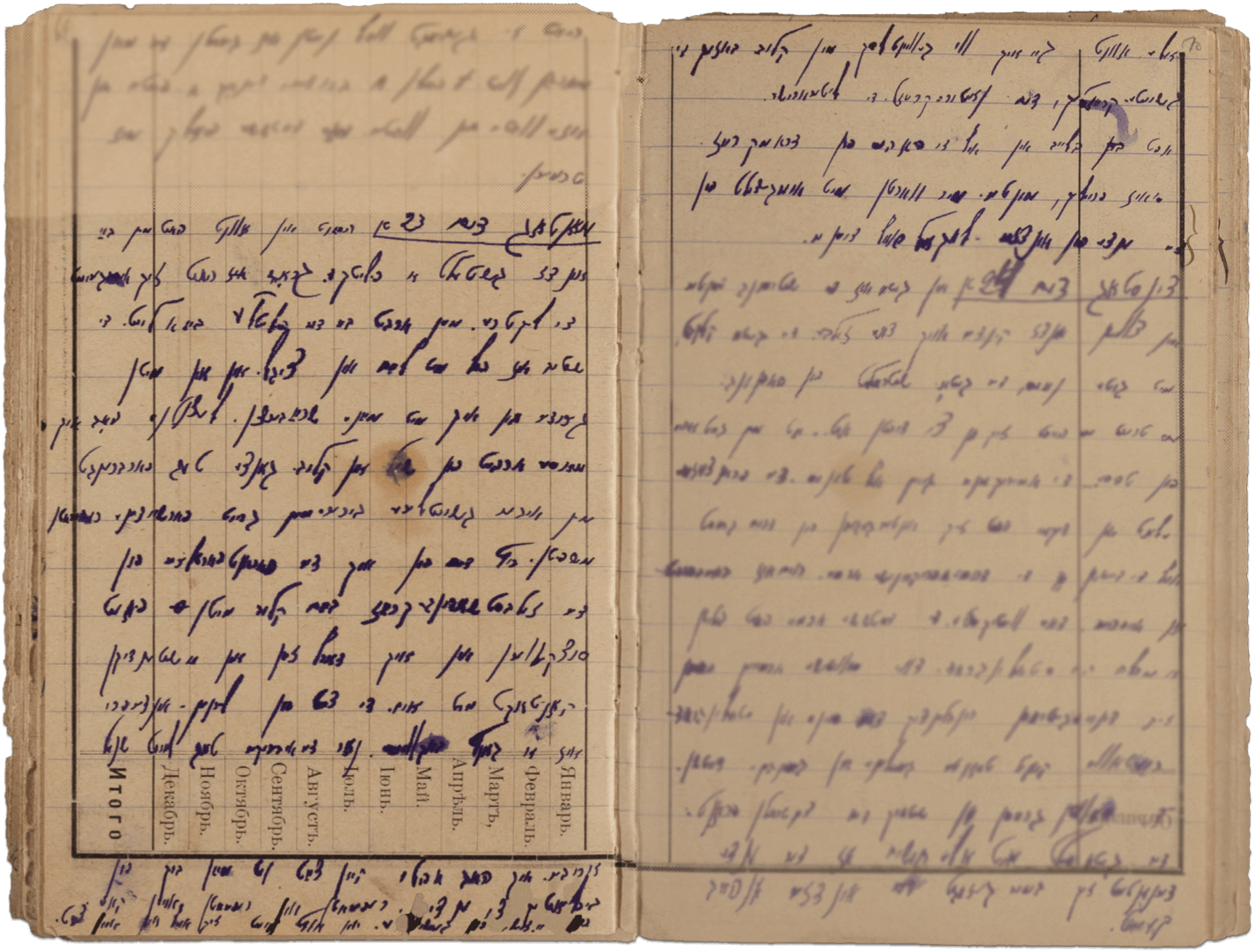

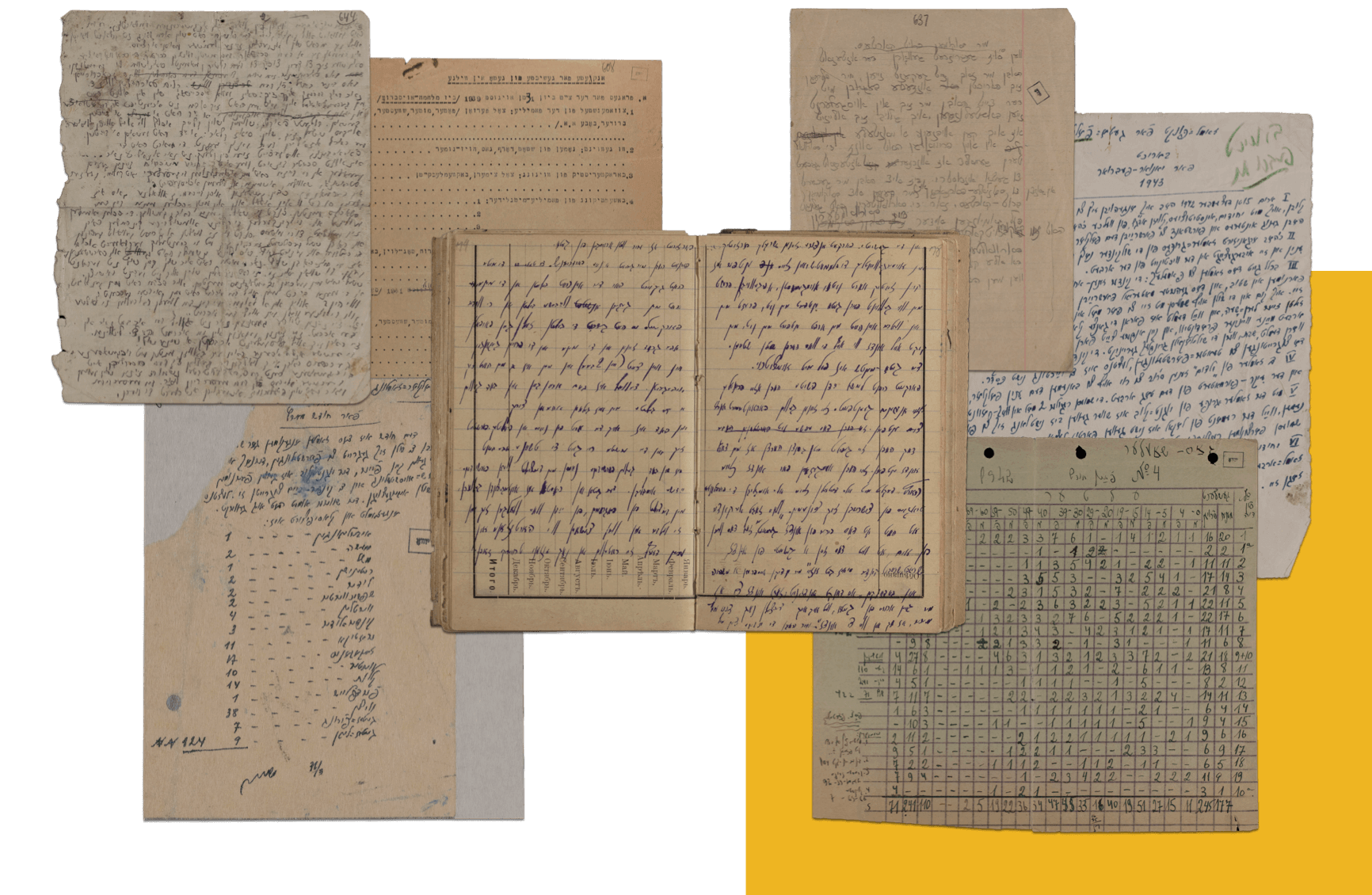

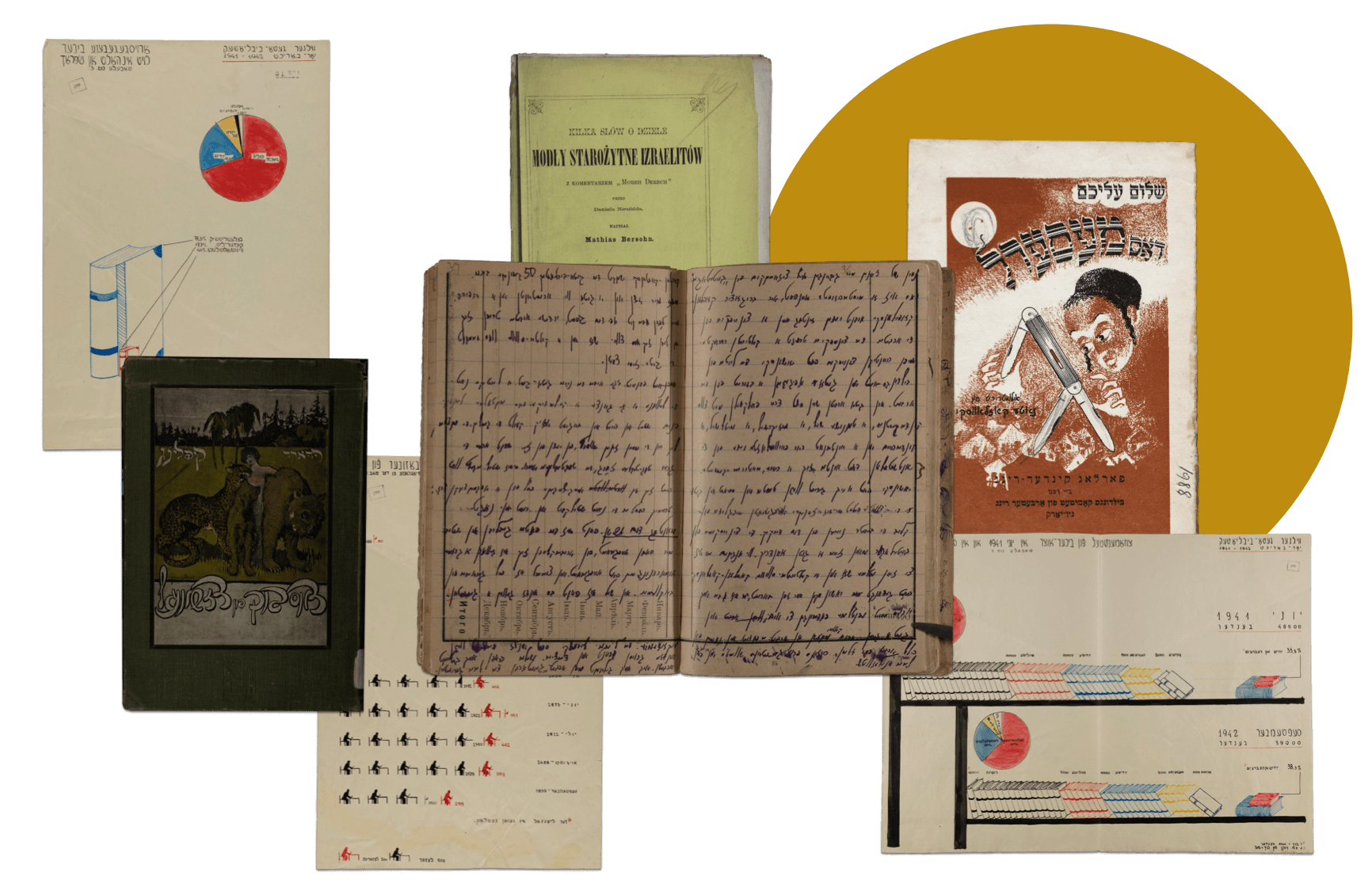

The group known as the “Paper Brigade” was largely composed of people who had connections to YIVO in pre-war Vilna, including Avrom Sutzkever, Shmerke Kaczerginski, and others. They were forced by the Nazis to sort through looted Jewish artifacts and curate the most significant objects, which the Nazis planned to display as historical artifacts of an “extinct race” after exterminating Jewish life in Europe. At tremendous risk to their own lives, they resisted these orders, smuggling many of these important artifacts and documents into various hiding places in the ghetto. Alongside this task, the Paper Brigade also created a Vilna Ghetto Archive. The archive preserved documents of daily life as well as intangible experiences of the ghetto, transcribing oral histories and recording folklore from both adults and children. Knowing that many would be killed without any record of their experiences, the Paper Brigade sought to document everything they could for posterity. The project was quite successful, as much of it has been preserved to this day. In fact, many of the artifacts presented throughout this exhibition were originally collected for the Vilna Ghetto Archive. Here, you’ll find a selection of artifacts related to the work involved in developing such materials.

“At our ghetto-research circle we have decided once and for all to finish the hard work, that is, to go around to the homes with the questionnaires. We want to start going over the answers and on the basis of the materials, to create history. Today my friend and I were in a new home. They gave us good answers. [. . .] Conversely, today, for example, simple Jews answered us in such a friendly and agreeable way. They were interested in answering us. [They may not have understood it, but] still they felt with all their heart that they ought to answer us. They poured out their hearts for us, spelled out with all the details of all their misfortunes, the complicated tragedies of adding names to their certificates. 'What do you say, children, this is what that Führer has made of us, may they make the same of him. That will be our history. Write, write, children, it’s good that you’re doing that.' We finish interviewing a family and say thank you. 'Oh, don’t thank us, promise us that we will leave the ghetto and we will tell you three times as much, poor wretches that we are.' We assured the woman ten times that we will leave the ghetto.”

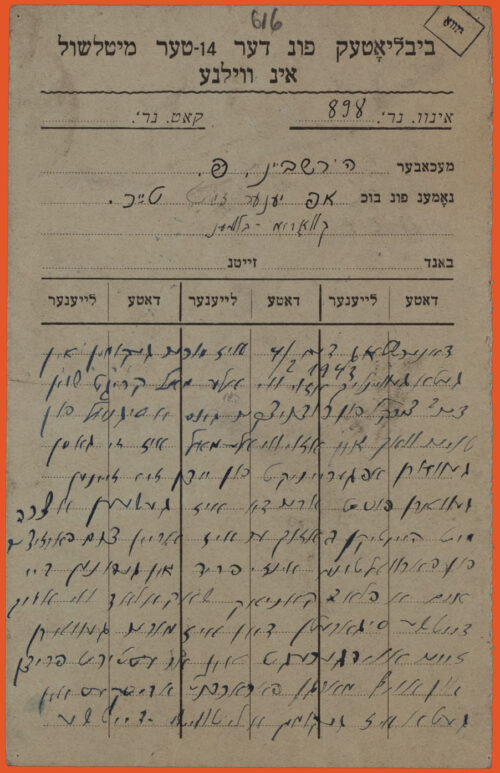

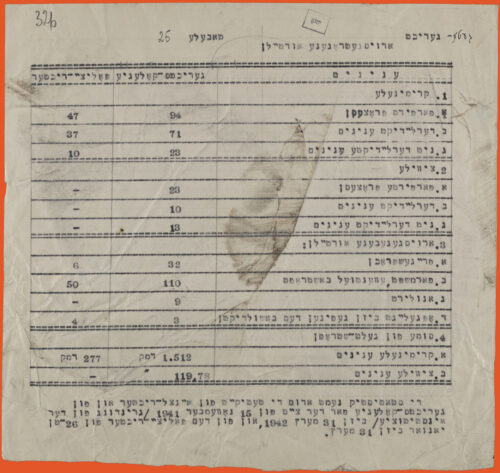

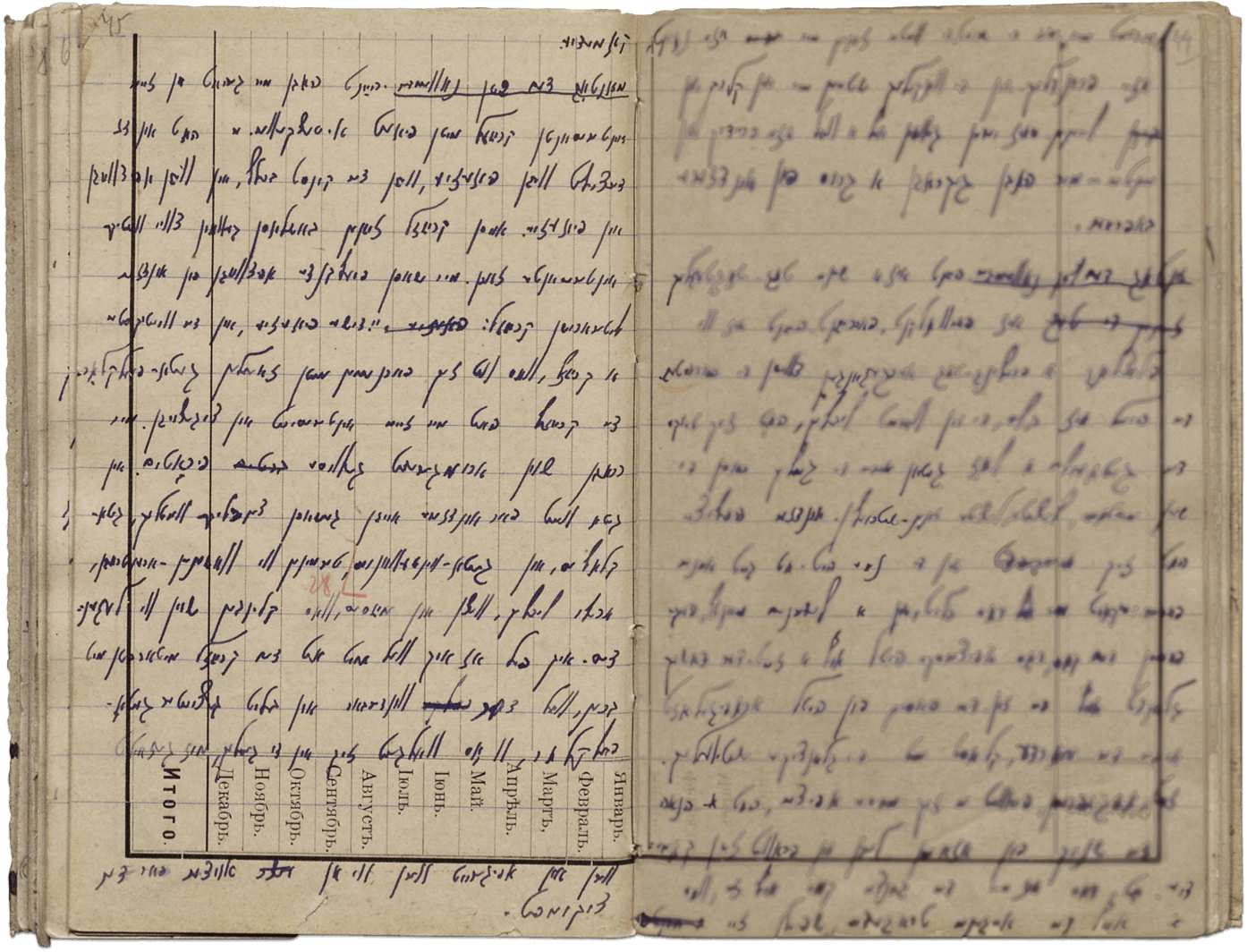

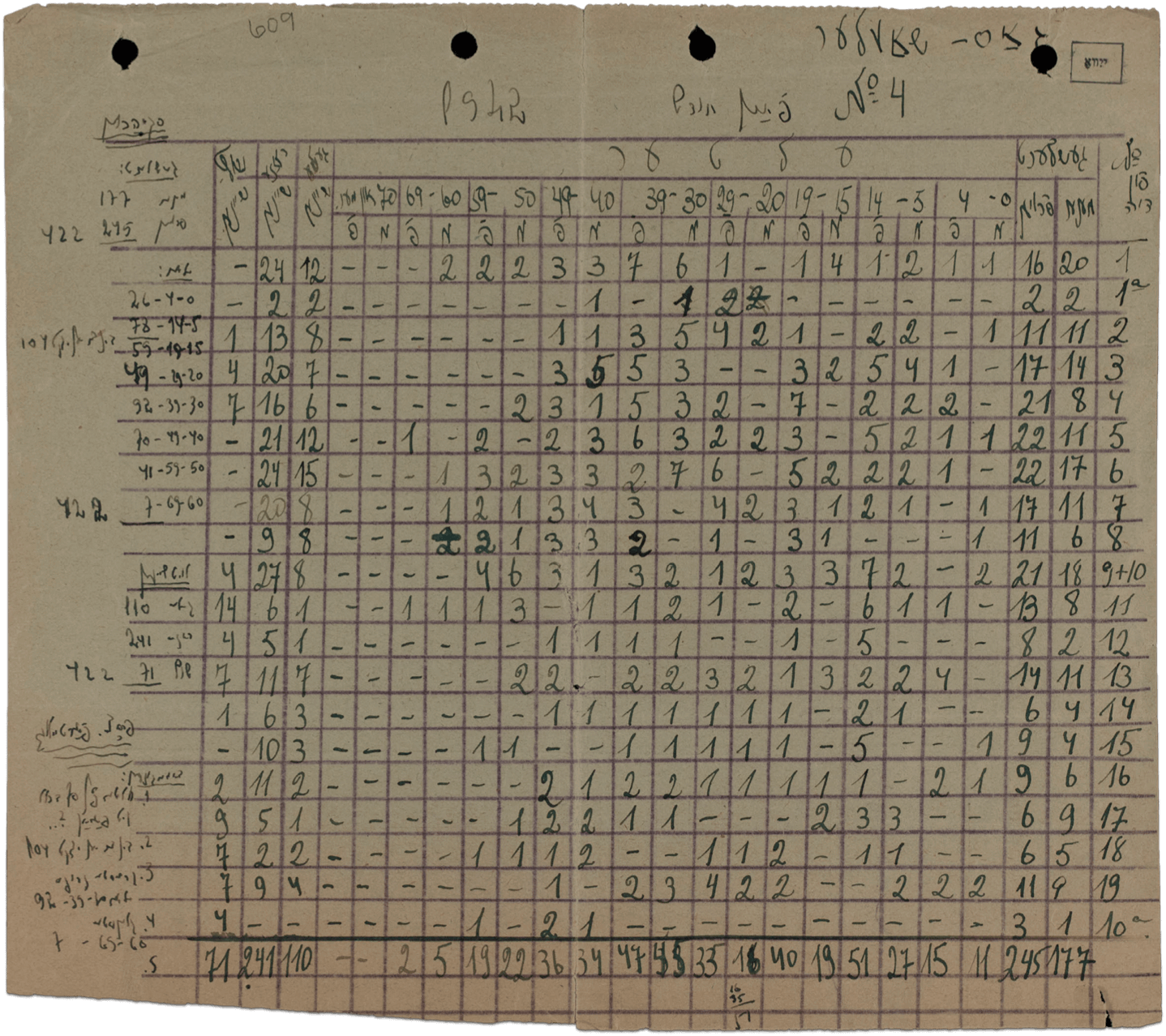

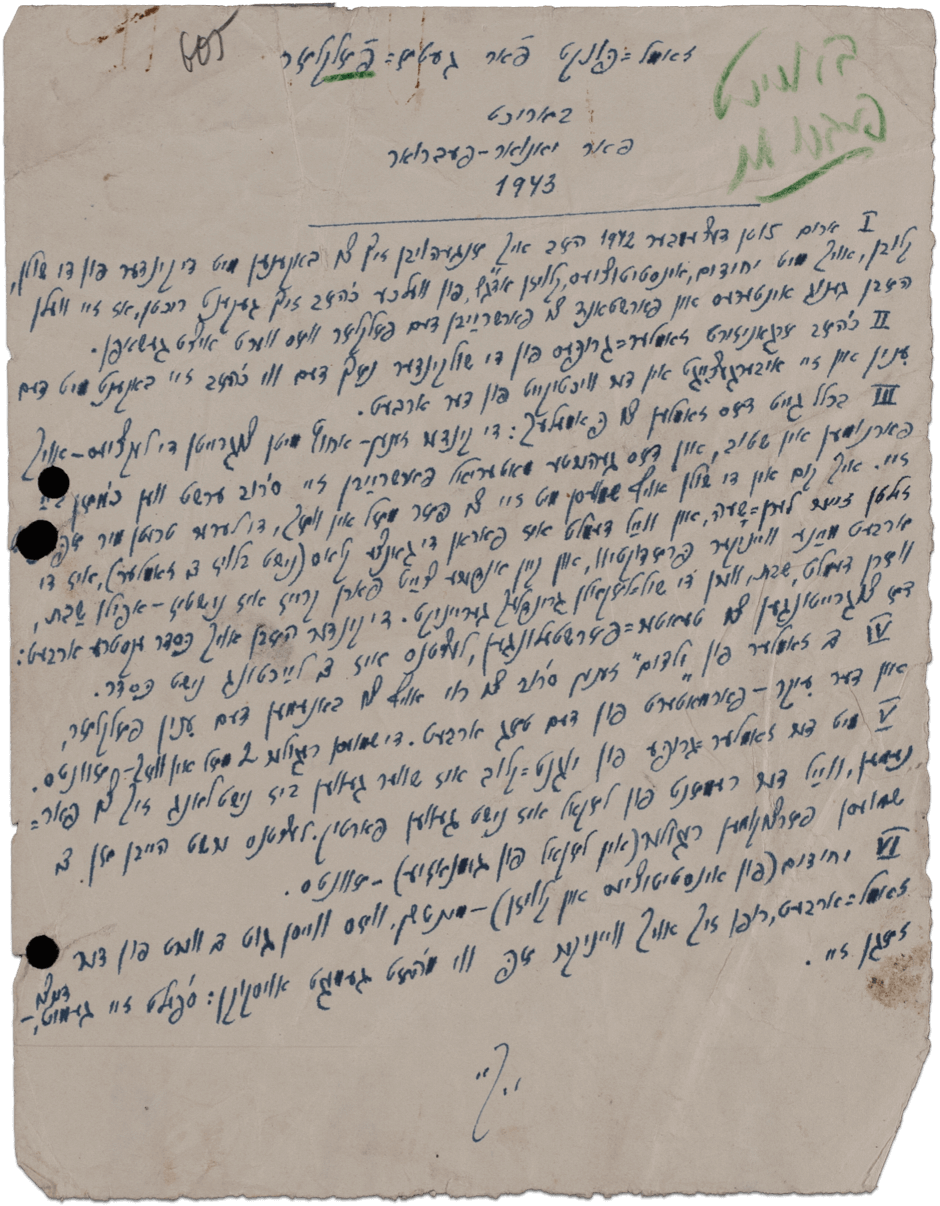

This table is titled “Shavler Street, No. 4 for the Month, 1942,” with columns labeled (from right to left) “sex,” “age,” “yellow passes,” “rose passes,” and “[shuts] passes.” Shuts means “protective,” a kind of pass that was added to relatives who had other, better, passes. This table was used for surveys with ghetto inmates.

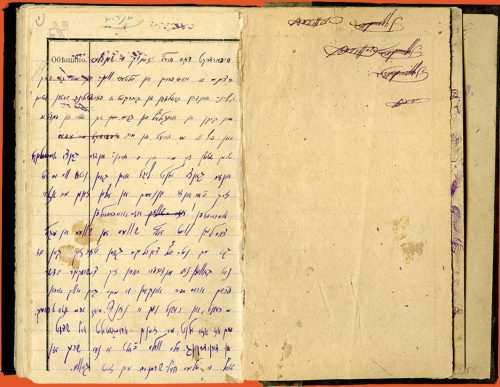

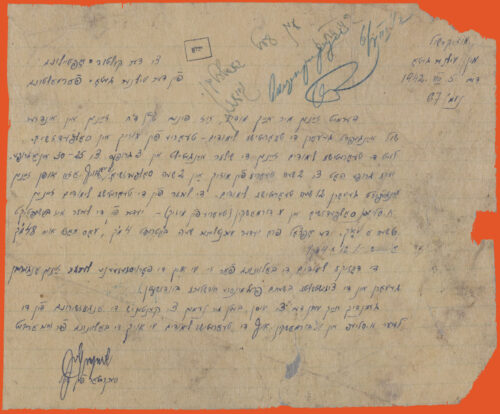

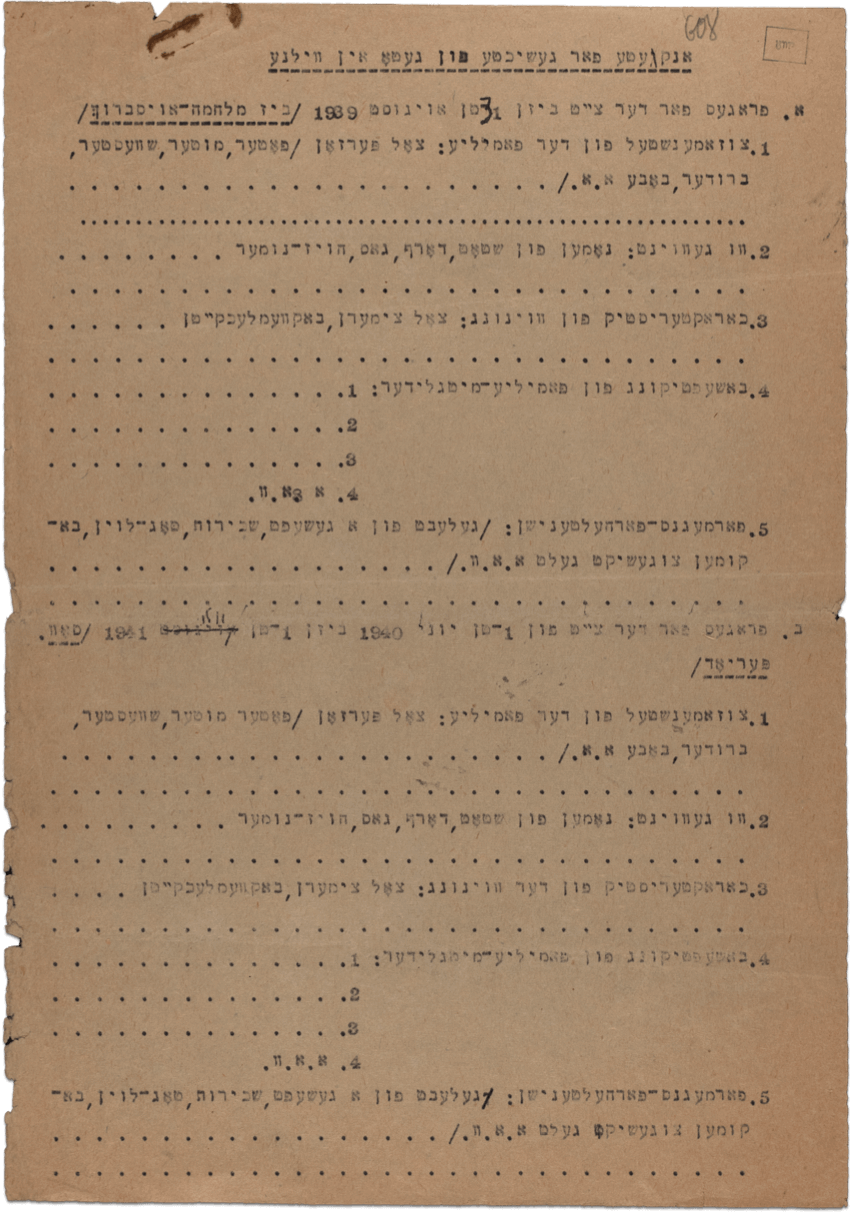

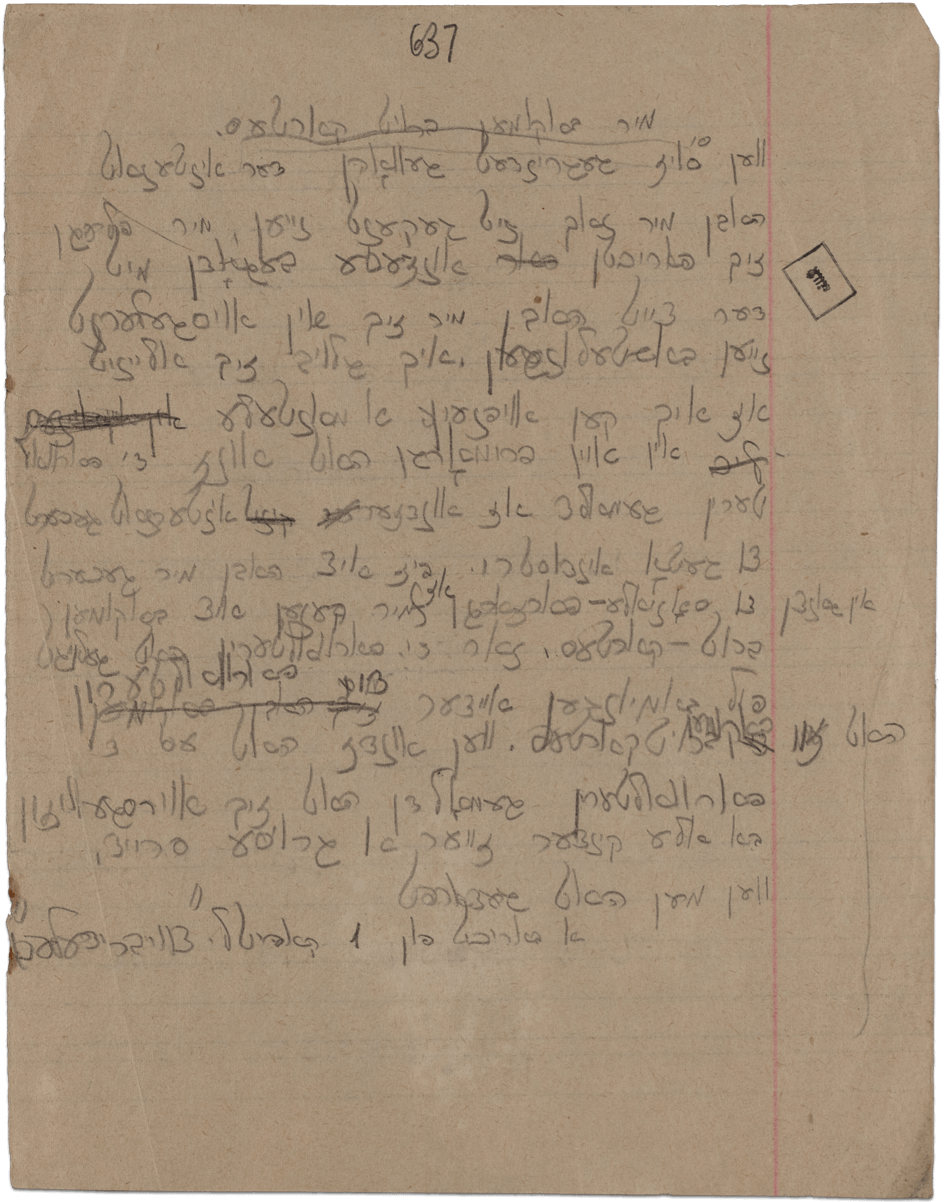

A questionnaire used to collect information about ghetto residents to preserve the ghetto’s history. The questions are divided into categories by time period and by employment in the ghetto period. These interviews were conducted by students like Rudashevski. People were glad to answer and talk to the students.

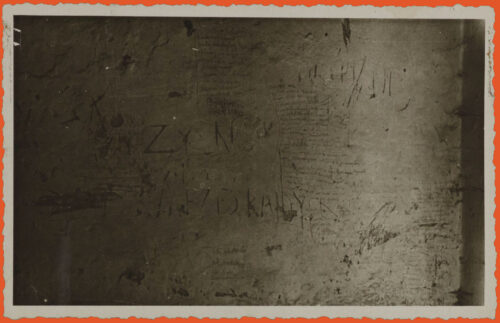

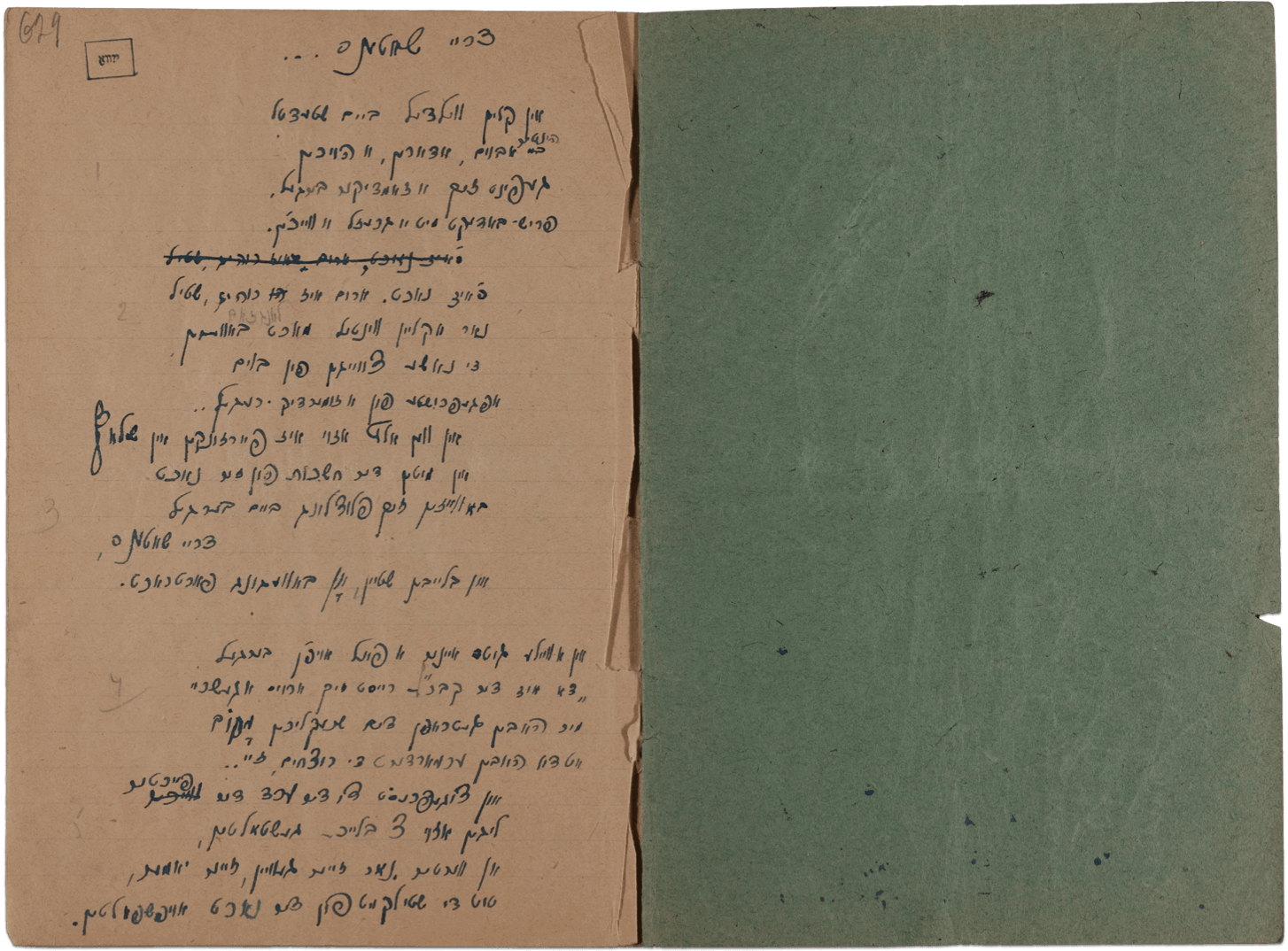

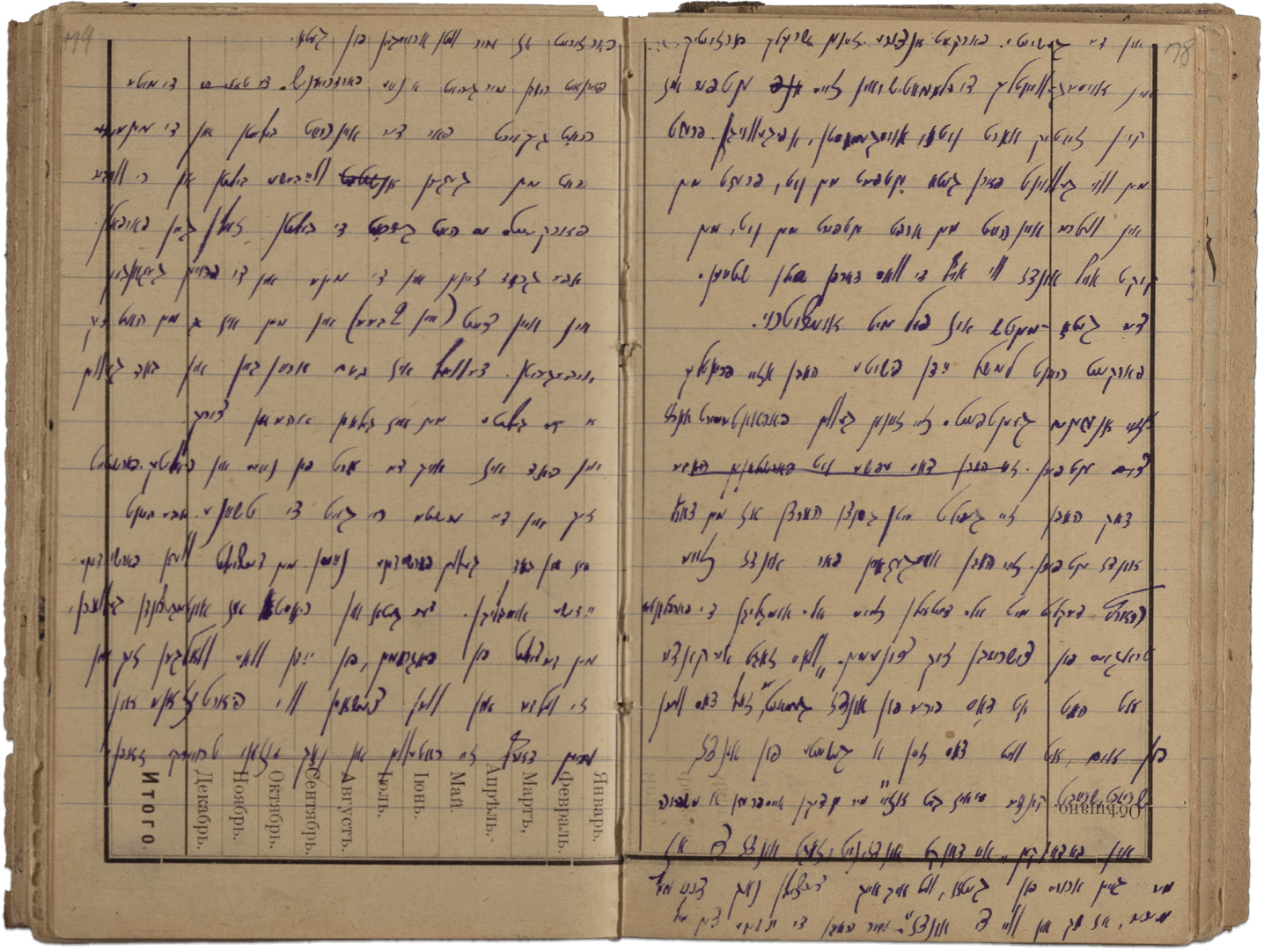

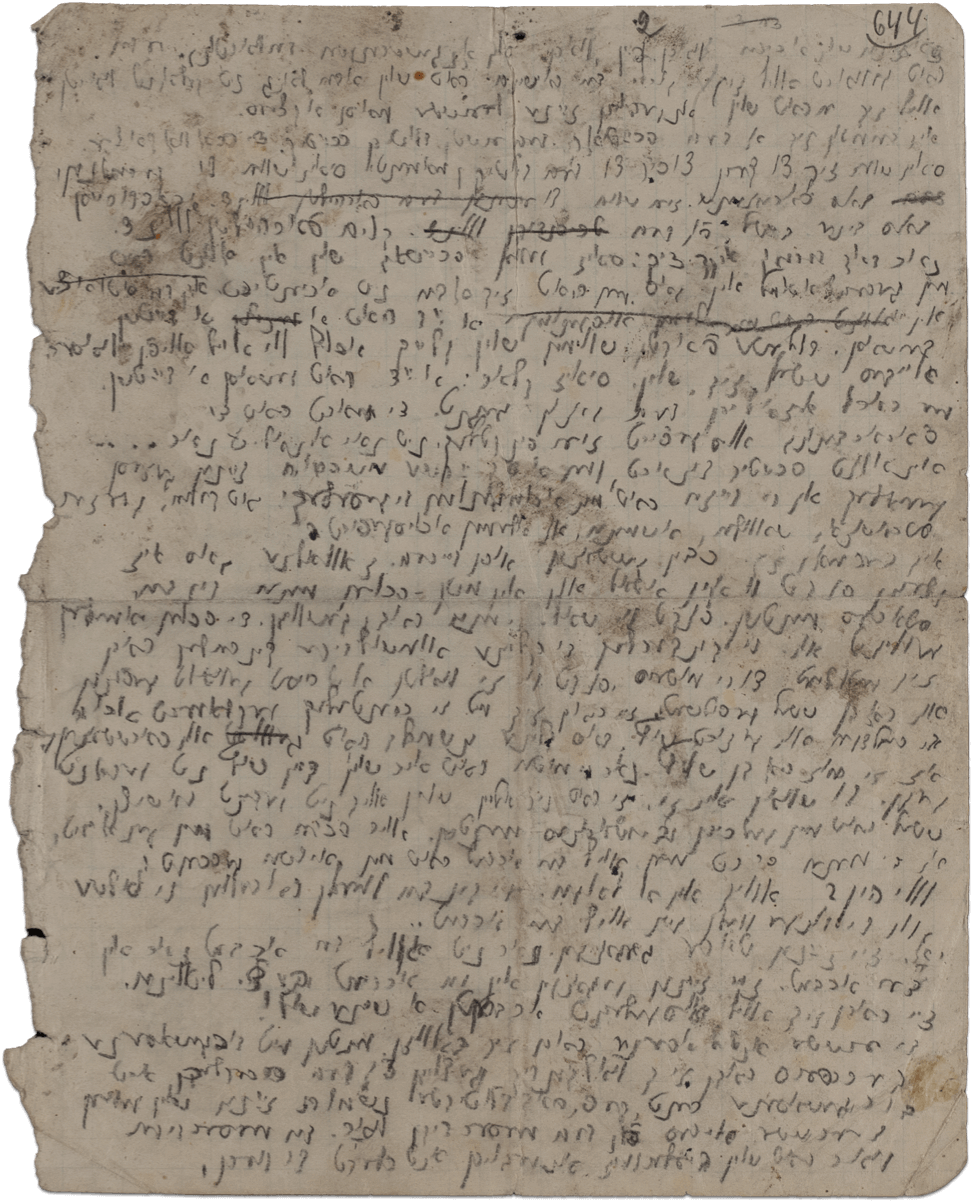

An uncredited, handwritten account of the Vilna Ghetto.

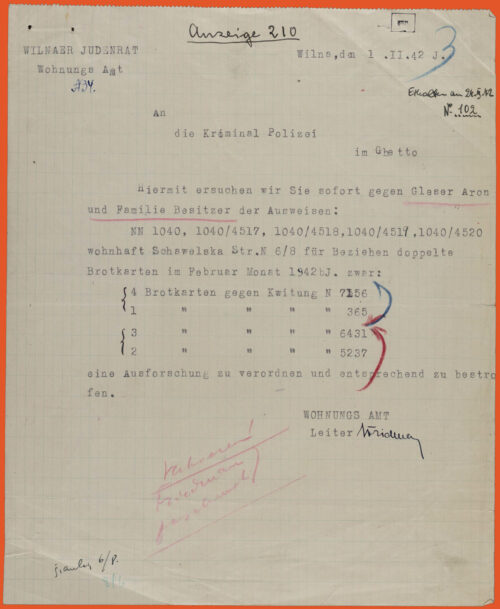

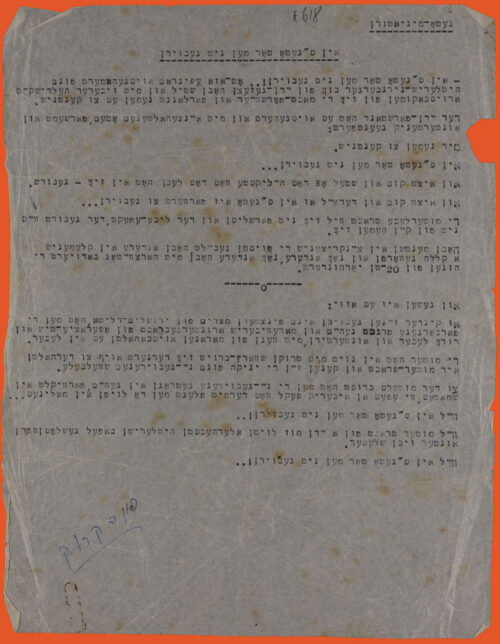

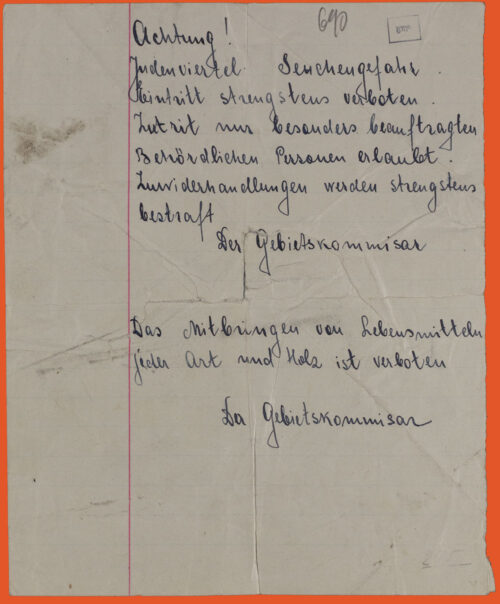

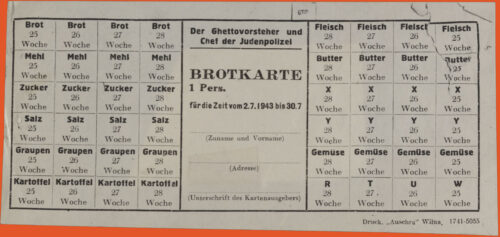

Note by a child from the report, "Tsvey briderlekh," titled “We receive bread ration cards.”

Report from the “Collection Point for Ghetto Folklore” about collecting ghetto folklore among the school children in the Vilna Ghetto.

A March 1943 report about collecting ghetto folklore among the school children in the Vilna Ghetto, detailing a total of 124 items covering different categories: jokes, parables, stories, songs, and more.

By September 18, 1941 – mere days after the establishment of the Vilna Ghetto – the ghetto library was already in service, taking over the building and collections of an existing library. The library was run by Herman Kruk, a librarian, who was able to employ many residents of the ghetto, giving them additional protection against the Nazis. Before the war, Herman Kruk led the Bund’s Grosser Library in Warsaw, one of the largest Jewish libraries in Poland. While having a library in the ghetto meant the residents had access to more information than they could individually possess, it also meant that Nazis could control what information the ghetto residents could access. Eventually, the Nazis ordered residents to turn their personal books in to the library. Then, they could control the information at its source. Still, the Jewish library employees worked hard to preserve the same information their oppressors attempted to suppress, hiding confiscated books in safe bunkers and using the pretext of being librarians to supply books to schools in the ghetto. Here, you’ll find books from the ghetto library, as well as records about the library’s usage.

“[…] After school we went to the meeting of the Beutelager. It is an outstanding labor unit. Its Brigadier, Kaplan-Kaplanski, organizes a meeting of the workers every Sunday. The meeting is of a cultural nature. At today’s meeting, Yashunski, the head of the Education Department in the ghetto, reported on the work of the Department. In the ghetto right now there are already functioning three elementary schools with three kindergartens, a technical school, a music school, a high school, a children’s home and an orphanage for abandoned youth. Each of these institutions has behind it a rich history of martyrdom. Yashunski also spoke about theater and sport in the ghetto. […] Kaplan-Kaplanski donates 50 salvaged books to the ghetto-library. We sit in the ghetto like convicts in a prison, but we do not let our spirits droop. Jewish workers meet and enjoy two hours spent in a cultural environment that recalls the good, sweet times.”

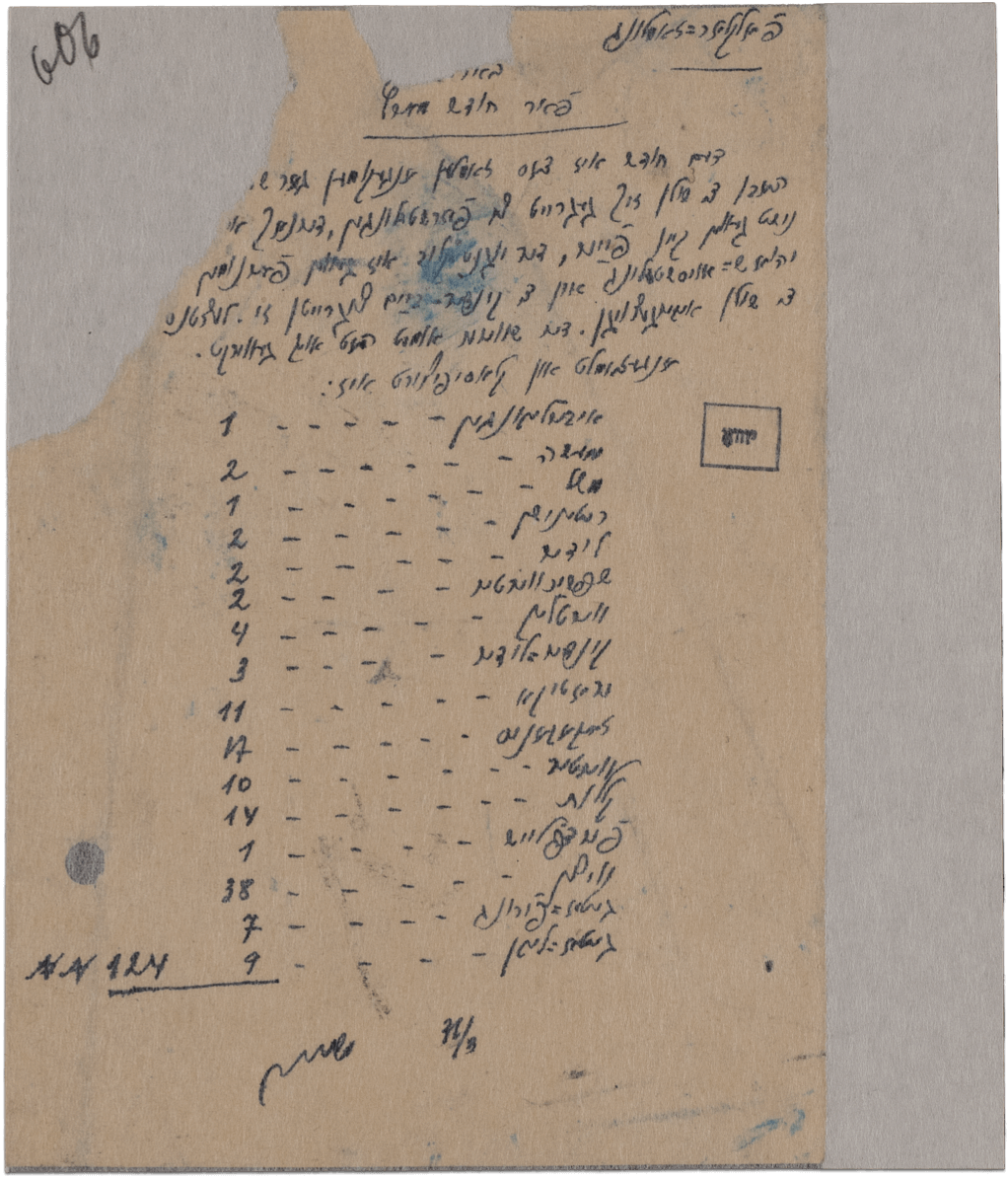

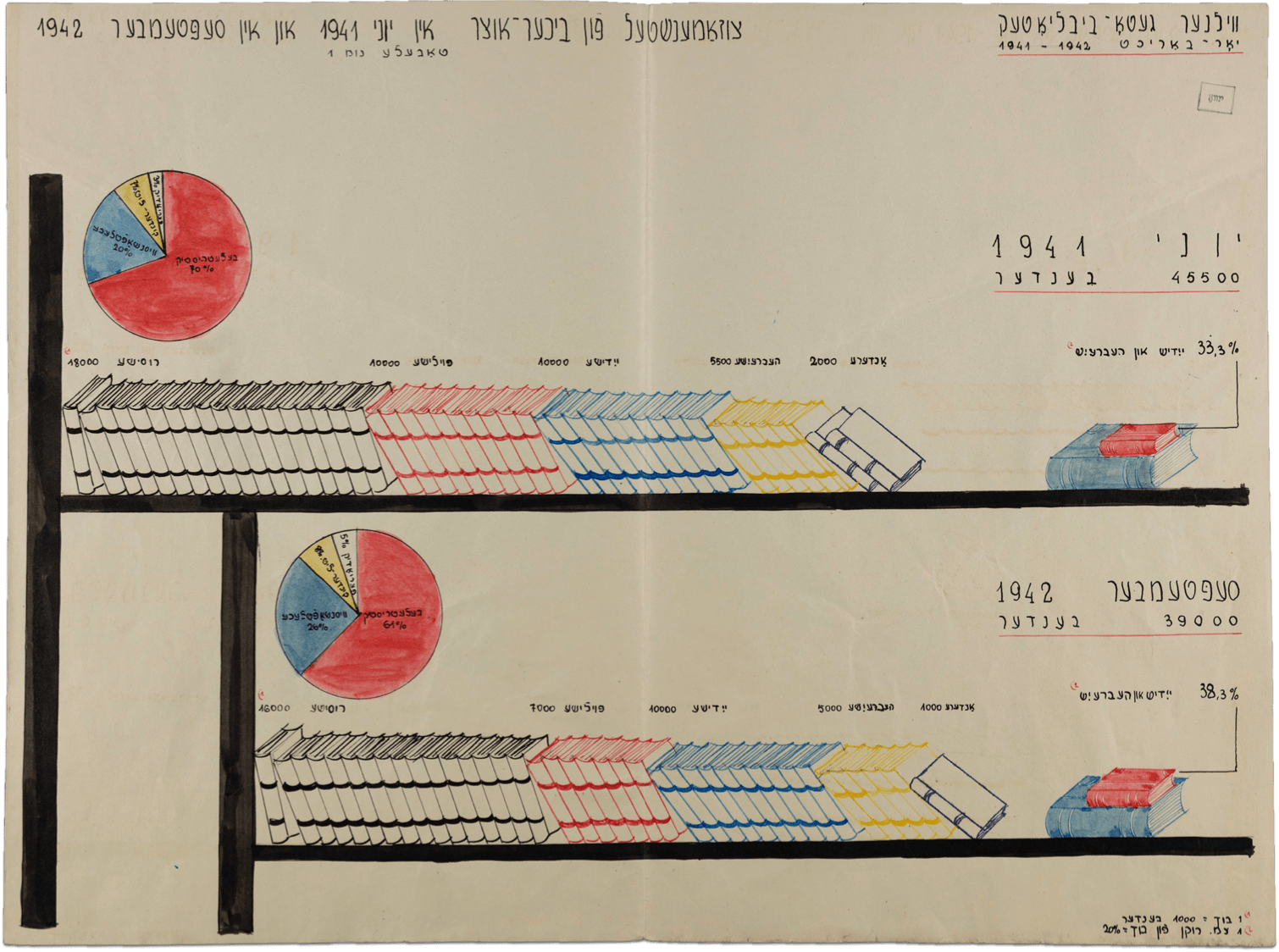

A visual representation of the the ghetto library's book collections compared with its pre-war collection.

First chart reads: “June 1941: 45500 Volumes.”

Pie chart: “Belletristic: 70%, Research: 20%, Children’s Lit.: 7%, Periodicals: 3%.”

Upper right book stack: “Yiddish and Hebrew: 33.3%.”

Upper shelf: “Russian: 18000, Polish: 10000, Yiddish: 10000, Hebrew: 5500, Other: 2000.”

Second chart reads: “September 1942: 39000 Volumes.”

Pie chart: “Belletristic: 61%, Research: 26%, Children’s Lit.: 8%, Periodicals: 5%.”

Lower right book stack: “Yiddish and Hebrew: 38.3%.”

Lower shelf: “Russian: 16000, Polish: 7000, Yiddish: 10000, Hebrew: 5000, Other: 1000.”

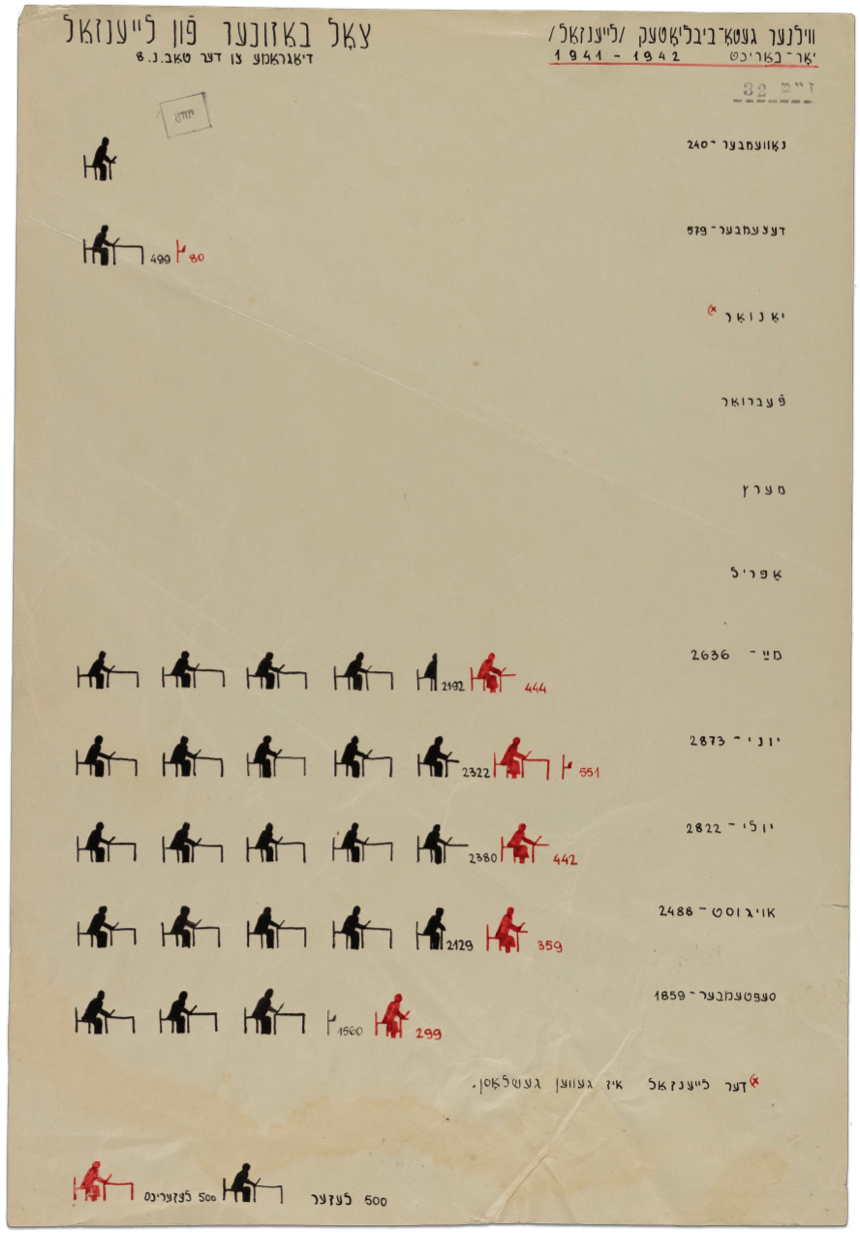

“Vilna Ghetto Library/Reading Room/Year Report 1941-1942: Number of Users of the Reading Room, Diagrams for Table No. 8.”

User statistics are as follows:

November – 240 men

December – 579: 499 men, 80 women

January*

February

March

April

May – 2636: 2192 men, 444 women

June – 2873: 2322 men, 551 women

July – 2822: 2380 men, 442 women

August – 2488: 2129 men, 359 women

September – 1859: 1560 men, 299 women

*The library was closed

[Black symbol] represents 500 male readers

[Red symbol] represents 500 female readers

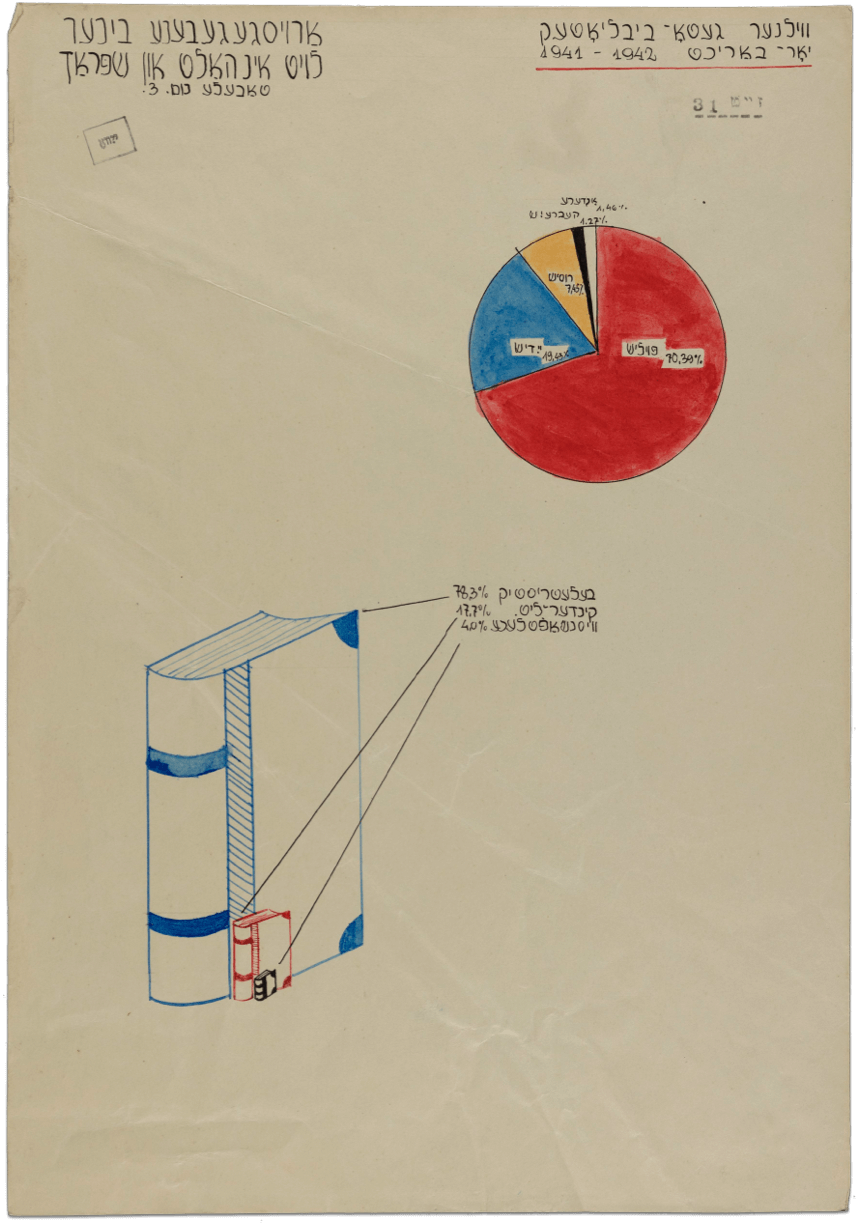

“Vilna Ghetto Library Year Report 1941-1942: Books Given Out by Contents and Language, Table Num. 3.”

Pie chart: Polish: 70.39%, Yiddish: 19.43%, Russian: 7.45%, Hebrew: 1.27%, Other: 1.46%.

Books: Literature: 78.3%, Children’s Literature: 17.7%, Research: 4.0%.

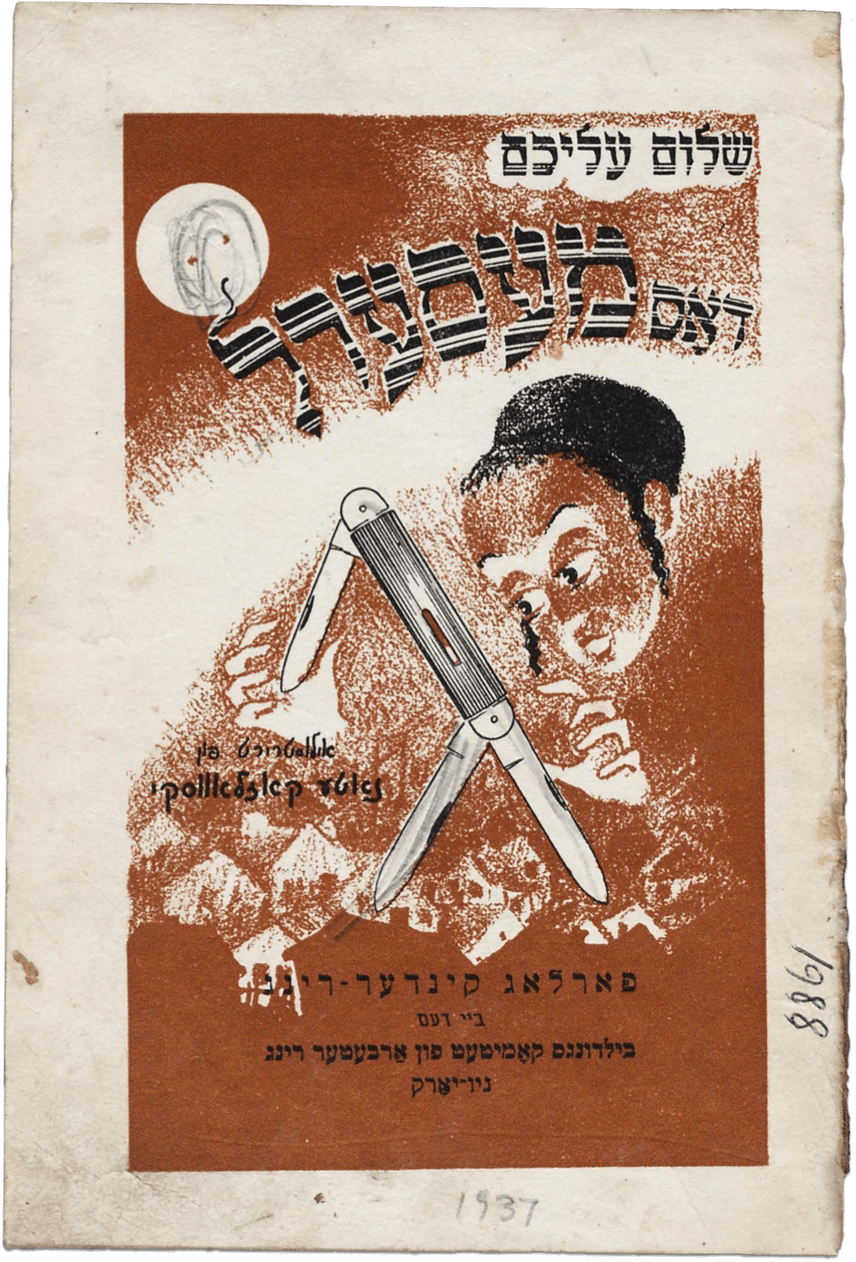

This was published in New York in 1937 by the Workmen’s Circle/Arbeter-Ring Educational Department to show that Yiddish literature was circulated worldwide.

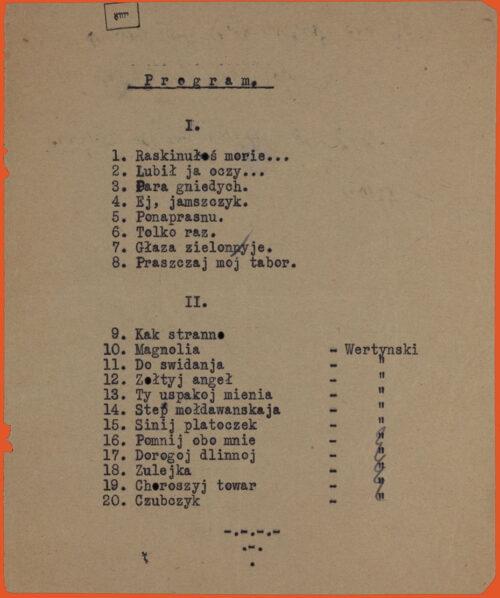

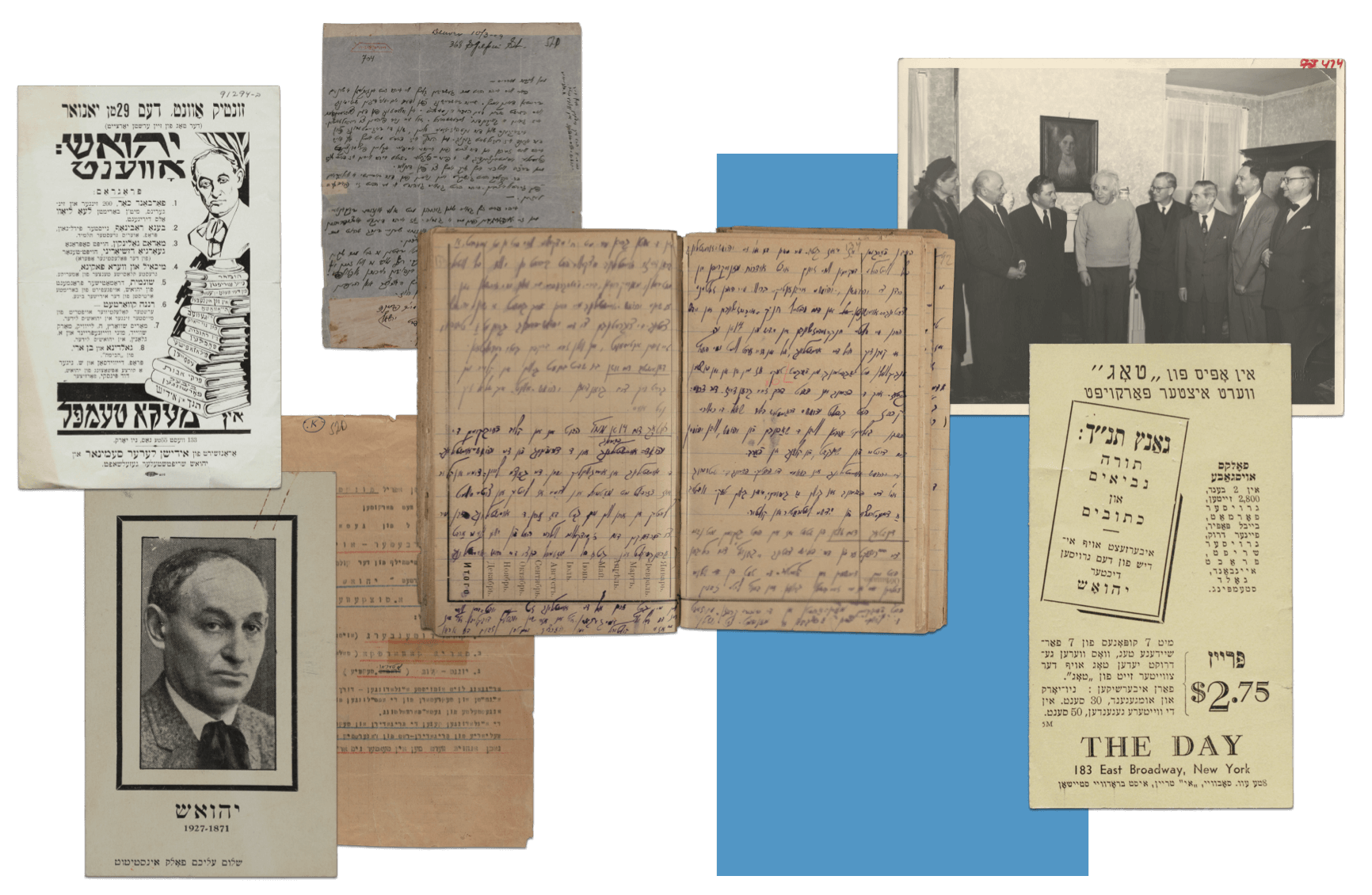

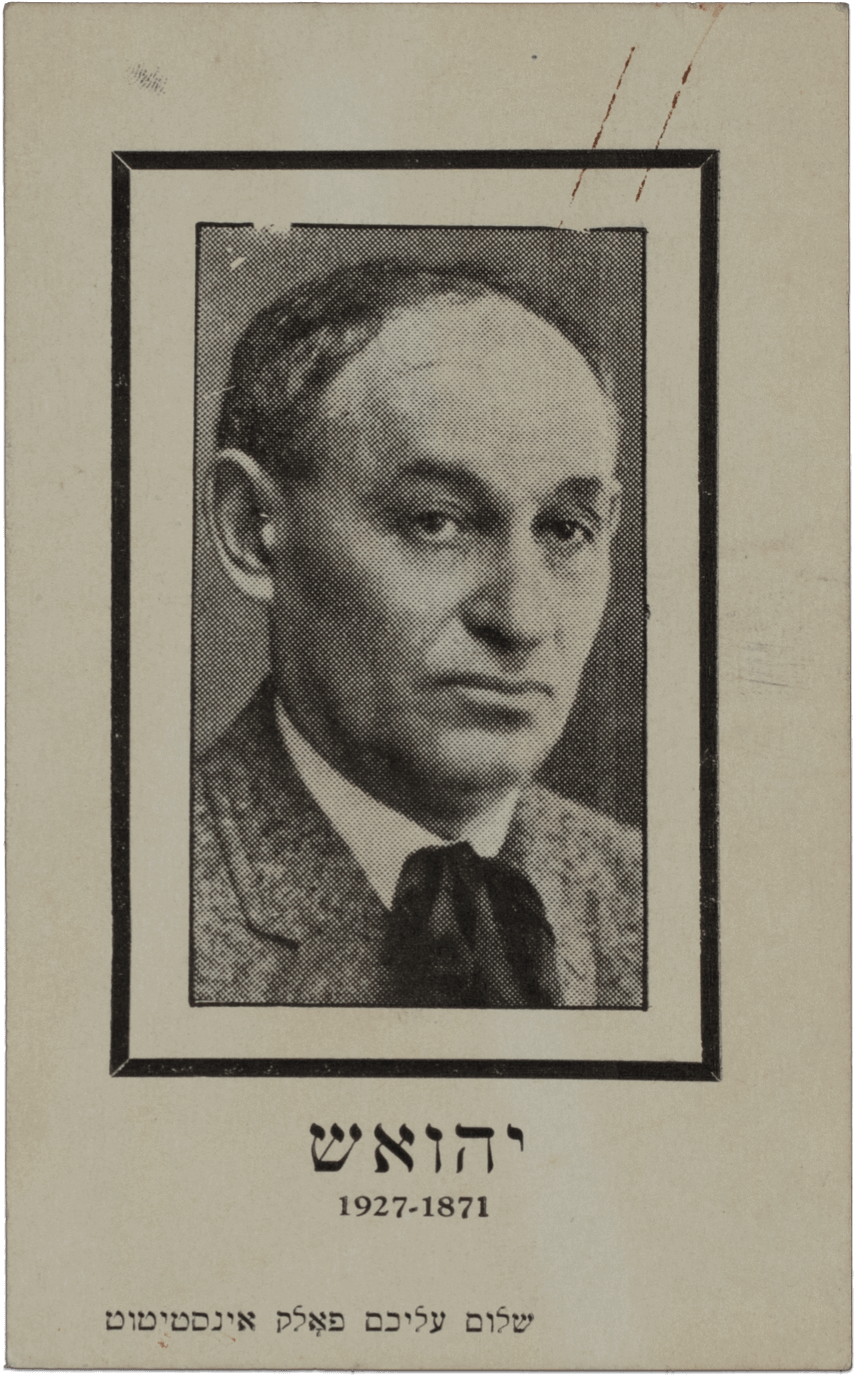

In Vilna and many other ghettos, residents found ways to ease their harsh living conditions through shared cultural experiences. Various groups, such as the Vilna Ghetto’s Youth Club, would regularly organize exhibitions and events featuring contributions from organizations and individuals in the ghetto. These exhibitions would often celebrate an esteemed figure from the world of Yiddish art and literature or display a range of artistic creations by ghetto residents. Rudashevski participated in the organization of at least one such exhibition, about the writer Yehoash. Yehoash was the pen name of Solomon Blumgarten, a poet and translator who lived from 1872 to 1927. Throughout his lifetime, Yehoash wrote many poems that reached international audiences and were widely translated. Perhaps most notably, Yehoash translated the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible, into Yiddish. This huge feat was widely celebrated and proved a great resource for many Jews who wished to read and study the Tanakh, but spoke better Yiddish than Hebrew. Here, you’ll see the exhibition’s program, a letter that was featured in the exhibition, and other materials about Yehoash.

“Today there took place in the Club the Yehoash celebration and the opening of the Yehoash exhibition. The exhibition is exceptionally beautiful. The whole reading-room in the Club is decorated with material. It is well-lit and tidy and your eyes light up when you go in. For this exhibition we have Kh. Sutzkever to thank. From YIVO, where he works, he was able to smuggle in a lot of material for the Yehoash exhibition. When you go into the exhibition, you see the youthful energy which gave full vent to everything here. Everything was selected in a beautiful and youthful way. Everything is so cultural and full of warmth. People came in here and forgot that they are in the ghetto. We have here in the exhibition many valuable documents that are now treasures. Manuscripts sent from Peretz to Yehoash, Yehoash’s handwritten letters. We have rare newspaper clippings. In the section “Tanakh [Hebrew Bible] Translations into Yiddish,” we have old Yiddish Tanakh-translations from the 17th century. Looking at the exhibition, at our work, your heart fills up with pride and enthusiasm. You really do forget that we are in a somber ghetto. The celebration today also went splendidly. The Dramatic Circle presented Yehoash’s dramatic scene “Saul.” Club members read their essays about Yehoash’s writings, about Yehoash the poet of beauty, sound and color. The mood at the celebration was lofty, it really was a holiday, a demonstration of Yiddish literature and culture.”

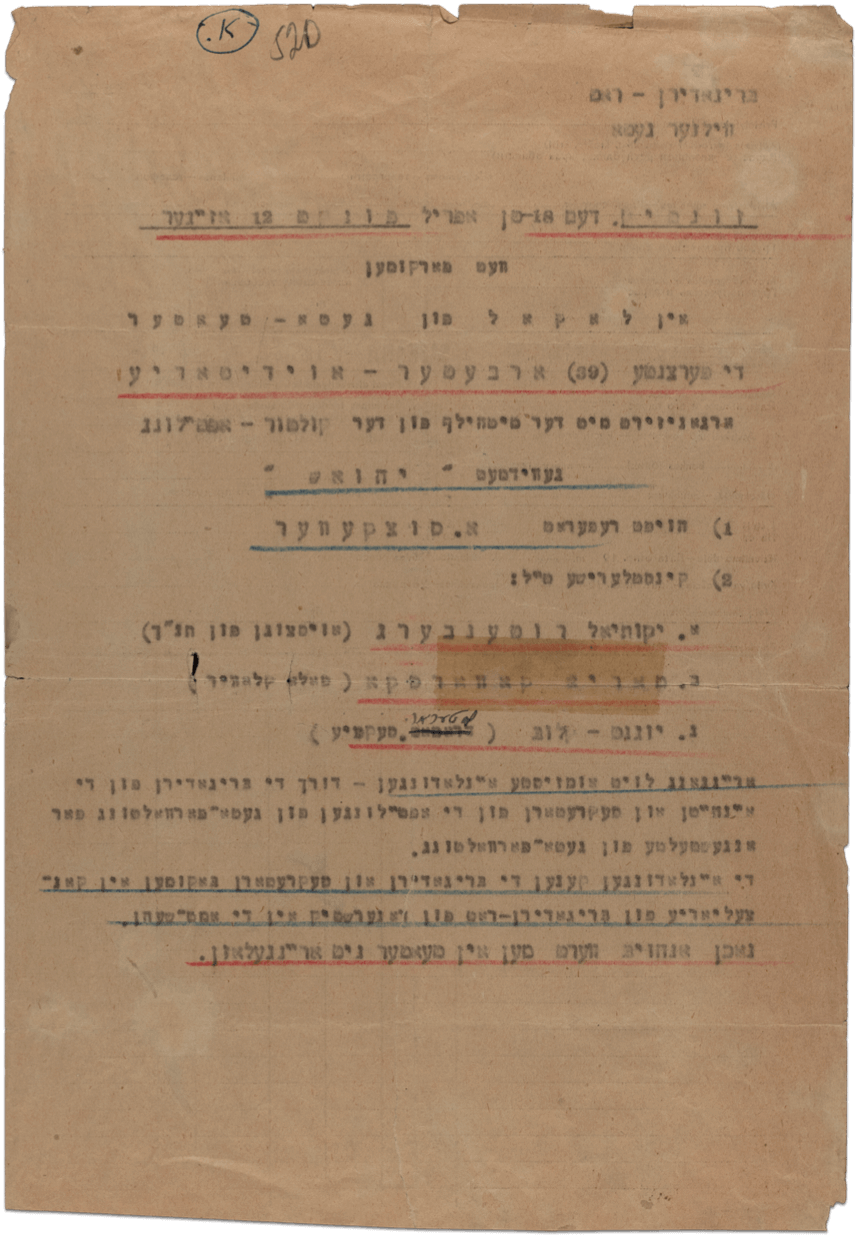

This is the actual poster advertising the Yehoash celebration and exhibition in the Vilna Ghetto on Sunday, April 18th [1943]. The noted Yiddish poet Avrom Sutskever was the primary speaker.

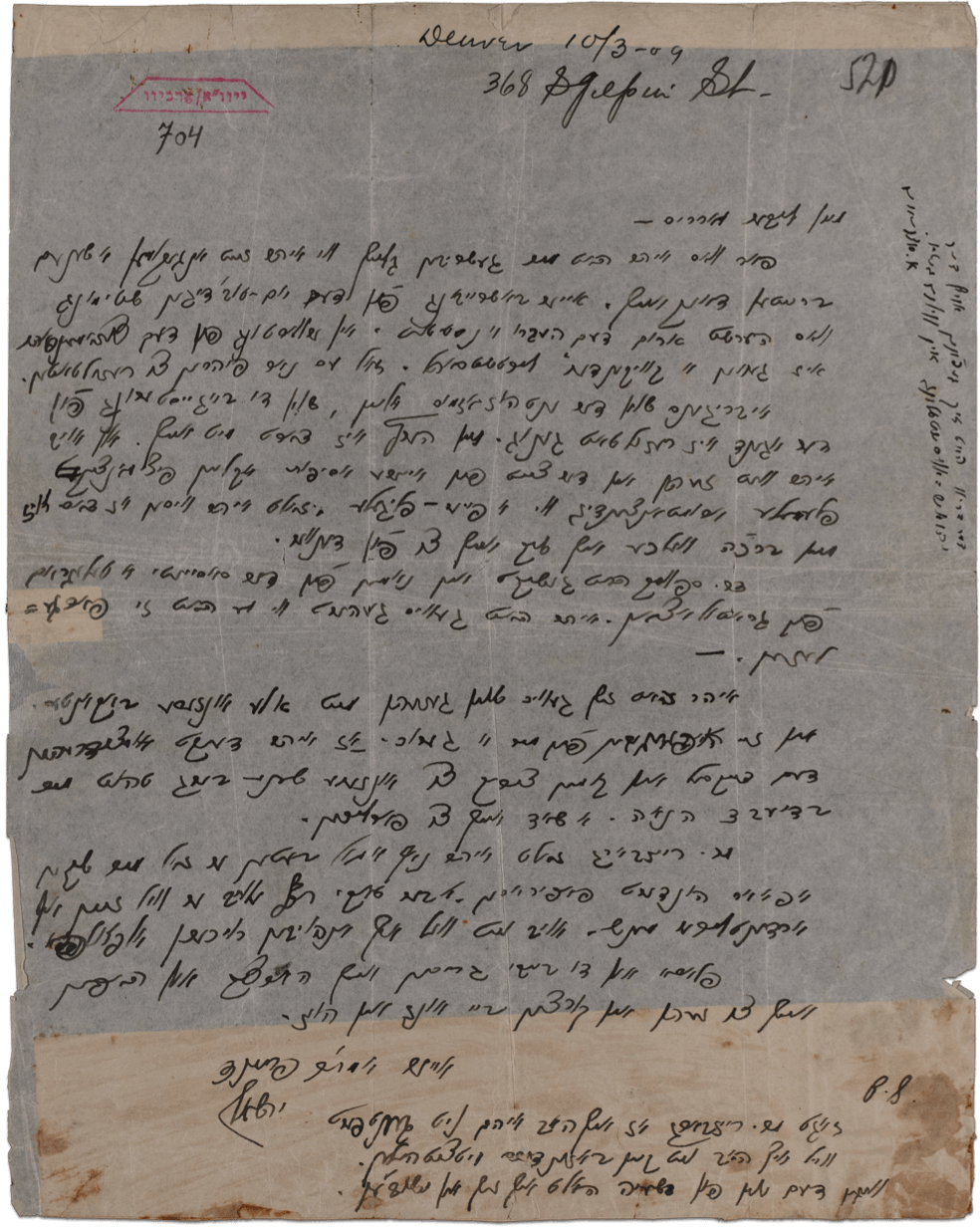

Letter by Yehoash to Morris [Rosenfeld] that was featured in the Vilna Ghetto exhibition. The letter was sent from Denver, where Yehoash had gone to treat his tuberculosis, like other Yiddish writers such as H. Leivick.

Advertisement for Yehoash’s translation of the Tanakh, printed in the New York Yiddish daily newspaper Der Tog. It enabled readers who cut out enough coupons from the paper to purchase Yehoash’s Yiddish translation of the entire Hebrew Bible at a reduced cost.

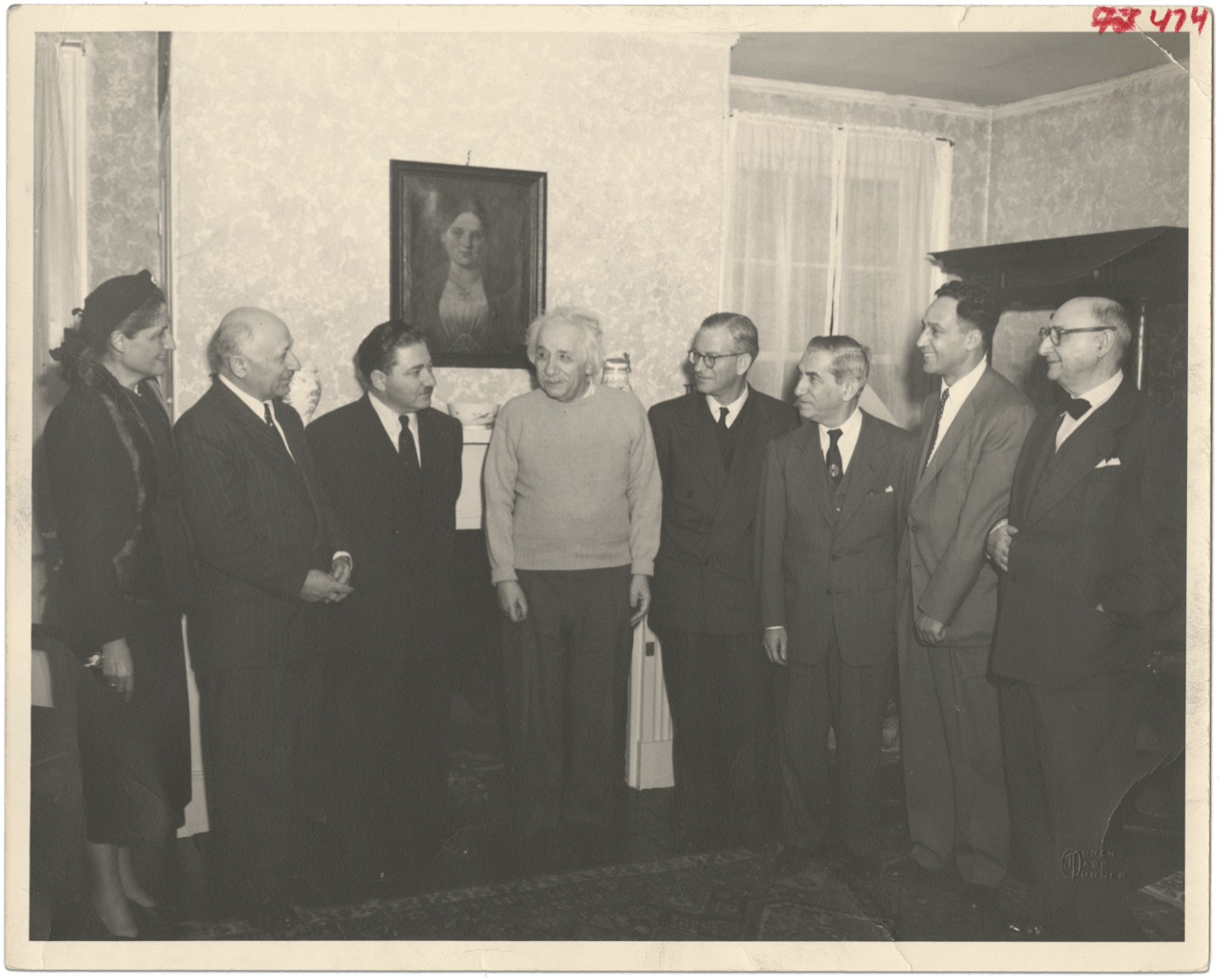

A delegation from the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants), including Yehoash's daughter, Evelyn, visits Albert Einstein. OSE was a Jewish Children’s Aid Society active in Eastern Europe headquartered in France at the time of this photo. It should not be confused with OZE, a different organization for the protection of the health of Jews founded in Tsarist Russia.

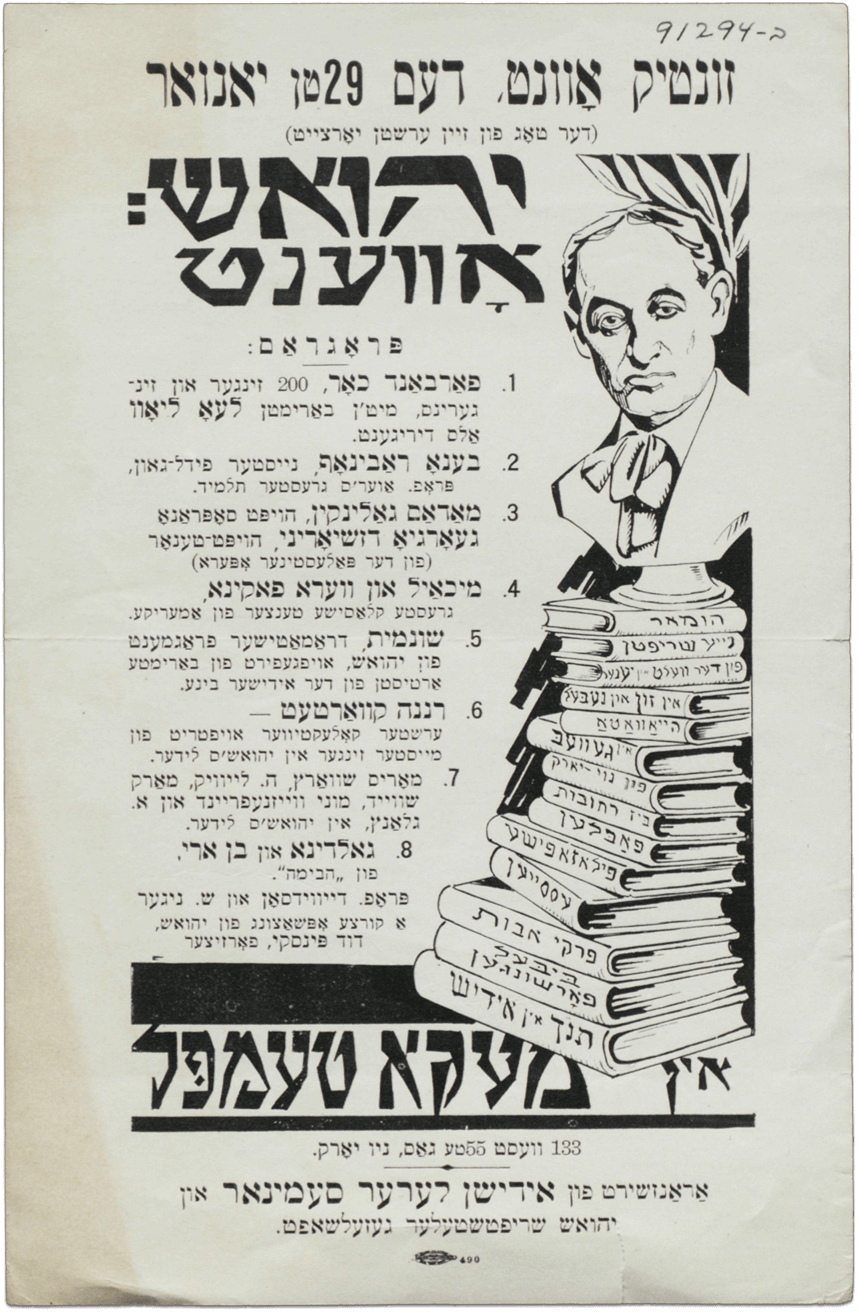

Program for an event honoring Yehoyash on the first anniversary of his death at the Mecca Temple in New York on January 29th, 1928. This hall was built by the Shriners, a Masonic organization, and is now the New York City Center.

Culture and Relationships

This section focuses on youth activities and the cultural resistance practiced by ghetto inhabitants. The resistance took the form of several activities: education, the Youth Club, history and folklore circles, mock trials, exhibitions, and memorials, among others. You’ll learn about Rudashevski’s experience in each of them through his diary entries.